Japan and South Korea: Strategic alignments

Japan and South Korea must both balance the United States and China in their geopolitical stance: one guarantees their security, the other holds huge sway over their economies. The two Northeast Asian countries are taking very different approaches to this situation.

In a nutshell

- South Korea and Japan depend on the U.S. for security

- Both prefer warmer relations with China for economic reasons

- In the long run, the U.S. will find Japan a more useful ally

Like many countries in the Western Pacific, Japan and South Korea have two inclinations in their foreign policy alignments. In times made uncertain by North Korean threats or Chinese coercive behavior, both seek to maximize the security that comes with their relationship with the United States. In more stable times, both balance U.S. ties against China’s growing influence on their economies. Yet the two countries take very different tacks.

South Korea’s overwhelming priority is fending off attack from North Korea. That is the basis of its robust security relationship with the U.S. Japan’s scope of interests is much broader, most prominently including geostrategic concerns over the rise of China.

The U.S. shares Japan’s worry over China. On the other hand, Japan’s constitution puts strict limits on its defense capabilities. Tokyo must therefore frame its security policy in the context of relations with the U.S. – an alliance that is slowly growing more ambitious. There are no such rising aspirations in the U.S.-South Korea relationship. Seoul remains overwhelmingly dedicated to the defense of the Korean Peninsula, and Washington is an indispensable ally in this cause.

As the U.S. moves into a great power competition with China, it will find Japan a more useful ally than South Korea.

For these reasons, as the U.S. moves into a great power competition with China, it will find Japan a more comprehensive and useful ally than South Korea. Washington will remain fully committed to defending South Korea from any potential North Korean attack. Once that rationale dissipates – by regime change or successful mitigation – both sides’ commitment to the alliance will become difficult to sustain. Tokyo will emerge as Washington’s clear partner of choice, while Seoul, left to its own devices and more distrustful of Japan than China, will drift in Beijing’s direction.

This all assumes continued Chinese coercive behavior. In a more conciliatory environment, Japan and especially South Korea would downplay differences with China and seek to maximize economic benefits from it. Even then, however, Tokyo would have a plan in case of renewed tensions. Seoul much less so. So, in good times and bad, the divergence between Japan and South Korea’s direction is apparent.

Facts & figures

The United States

For decades, Washington has served as a catalyst for peace and cooperation in the region. In the current context, it shields Tokyo from a rising China, and it gives Seoul comfort vis-a-vis its fears of a resurgent, hegemonic Japan. It offers both insurance against attack from North Korea. By assuming the lion’s share of responsibility for each of these challenges, the U.S. helps keep a lid on regional rivalries that would be aggravated if they were to be dealt with single-handedly by either Japan or South Korea.

Seoul and Tokyo carefully watch for any change in the U.S. position on these issues. In this regard, their responses to the Trump administration are not as negative as international media speculation would have it.

There are two reasons for this presence of mind. First, the Trump administration has sought to reassure the region of American staying power from its first months in office. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was the first world leader President-elect Donald Trump welcomed to the U.S., and the second to meet the new American president after his inauguration. During their first official meeting as heads of government, in February 2017, President Trump reaffirmed America’s treaty obligations to Japan and singled out its specific application to the Senkaku Islands.

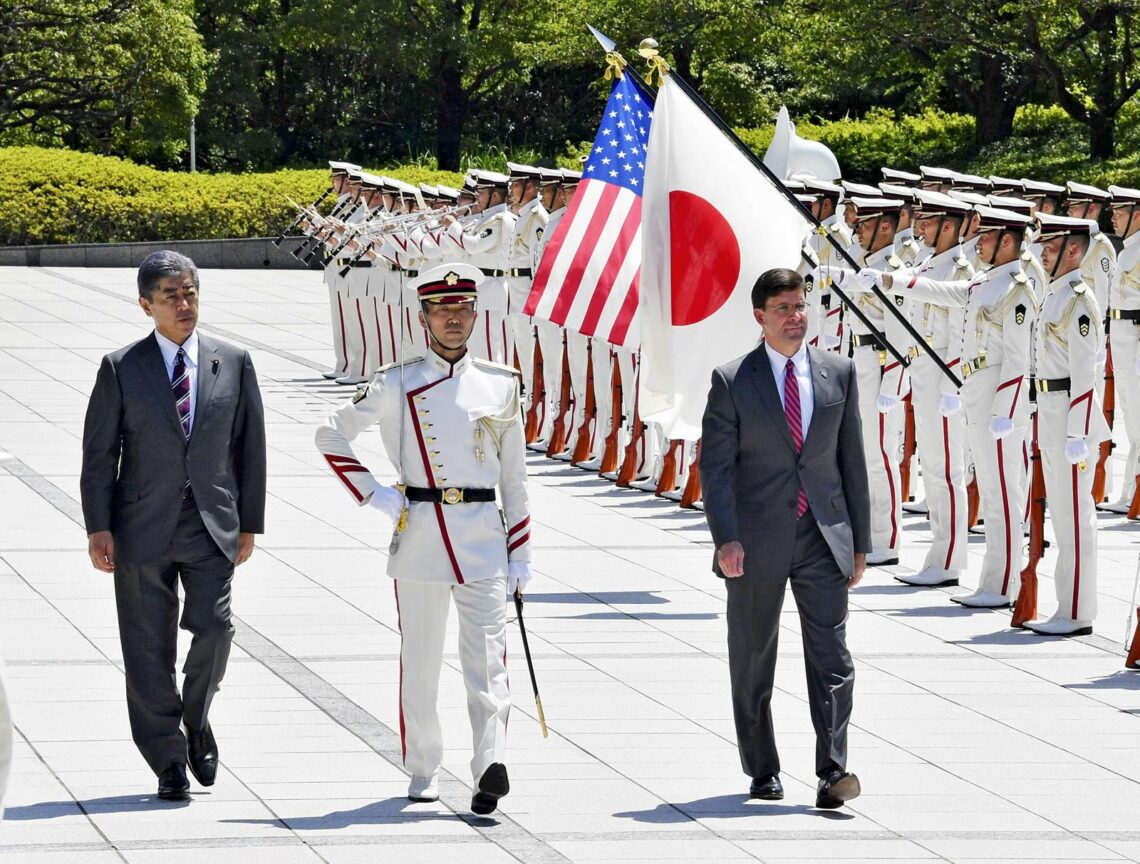

In between these top-level meetings, General Jim Mattis made his first overseas visits as secretary of defense to Japan and South Korea. His goal was to correct any misconceptions about U.S. commitment to its allies’ security. Throughout President Trump’s term, the Defense Department, State Department and the White House have all echoed such sentiments. Current Secretary of Defense Mark Esper’s first international trip after taking office was to the Asia-Pacific region and included stops in Japan and South Korea. This past January, President Trump, commemorating the 60th anniversary of the U.S.-Japan alliance, said he was confident that the partnership would “continue to thrive.”

Second, these diplomatic signals have coincided with a steady U.S. military presence in the region. Nothing has changed since President Trump’s inauguration. The U.S. continues to maintain its full slate of U.S. bases in Northeast Asia, more than 80,000 troops, the Seventh Fleet and a wide range of bilateral and multilateral military exercises.

In the case of U.S.-Japan defense cooperation, exercises have continued to “expand geographically and operationally, but also into new domains,” said U.S. Acting Assistant Secretary of Defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs David F. Helvey.

On the other hand, the U.S. and South Korea have curtailed their combined exercises on the Korean Peninsula as part of an effort to coax North Korea out of its nuclear and missile programs. Still, the U.S. presence on the Korean Peninsula remains unchanged. Underscoring the U.S. commitment to South Korea, Congress has passed successive annual defense bills prohibiting the reduction of U.S. troops there.

President Trump’s unique diplomatic style has not affected the U.S. position in the region as much as many had feared.

According to the Pew Research Center, confidence in the U.S. remains strong in Northeast Asia. Its perception as a reliable security ally holds firm despite contentious negotiations over the terms of its continuing basing requirements. Neither has its image as an economic leader suffered significantly in spite of the Trump administration’s revisionist approach to international trade. The two countries seem to have taken in stride moves such as withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, renegotiation of the U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement and unilateral tariffs imposed on both allies.

President Trump’s unique diplomatic style and America-first mantra are not popular in the region. The same Pew poll indicates a much lower level of trust for him than for his predecessor. Still, that has not affected the U.S. position in the region as much as many had feared. Officials in Seoul and Tokyo may blanch at occasional reports of President Trump’s flagging interest, but they have proved resilient in adapting to changing American presidential leadership styles. Good relationships at the highest level – especially between Mr. Trump and Mr. Abe – have helped, as have private assurances at lower levels of the administration.

Perceptions of China

China is a major economic force in Northeast Asia, in some ways (trade volumes, for instance) more important than the U.S. It is also much a more dependable diplomatic presence, which had already been the case before President Trump took office. One might assume there would be a corresponding positive association among the voting publics of Japan and South Korea. Yet, both hold decidedly negative opinions about China, more so in the former than in the latter. Likewise, they have higher opinions of Mr. Trump than of Chinese President Xi Jinping.

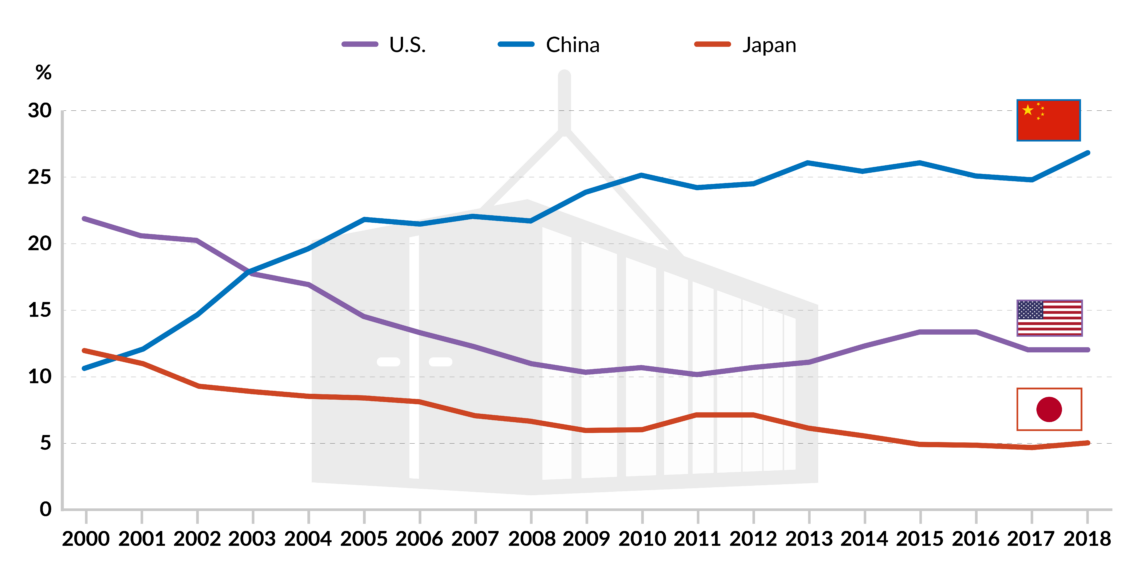

There are a couple of explanations for this. First, the economic picture is more complex than Chinese dominance. China is indeed the leading trading partner for both countries, in terms of both imports and exports. For South Korea, the phenomenon is particularly pronounced. In the case of Japan, however, the U.S. is a close second as a trading partner.

Japanese investment into China constitutes only about 6 percent of its total yearly outflow. Far more Japanese resources are invested in the U.S., the European Union, Singapore and the United Kingdom. Similarly, the U.S. is the biggest destination for South Korean investment abroad, with China only a slightly larger destination than it is for Japan. In neither country is China a major investor.

Facts & figures

Second, the disconnect between public attitudes and economic engagement is not unusual. Taiwan is proof of this. Even as the island’s economic dependence on mainland China has grown, Beijing’s aggressive attitude has hardened public opinion around issues of Taiwanese identity. China’s ongoing conflict with Japan over the Senkaku Islands has fed negative attitudes. The detention of Japanese nationals in China and, as in Australia, scandal associated with pro-Beijing parliamentarians may also play a role.

China’s retaliation against Seoul’s decision three years ago to deploy the American THAAD missile defense system left a lingering negative impression in the South Korean public’s mind. Beijing’s unofficial, unannounced sanctions included curtailing Chinese tourism to South Korea and essentially shutting down South Korean businesses operating in China. Because they were never officially imposed, it is difficult to tell if they have been lifted. The figures for tourism and reopened businesses would suggest they have not.

Other incidents have put strain on the relationship, such as Chinese support for North Korea following the sinking of a South Korean warship in 2010. Going back further, South Koreans know very well that Beijing backed Pyongyang during the Korean War and has remained a strong ally since.

As periods of tension pass, these factors tend to become less important. The Japanese and South Korean governments have taken advantage of Chinese efforts at conciliation of late and pursued rapprochement.

Following the dispute over the THAAD deployment, South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s government announced it would refrain from additional deployments, would not participate in America’s broader missile defense network and would not establish a trilateral alliance with the U.S. and Japan. The policy was known as “the three no’s.” The significance of the announcement was cosmetic – South Korea had never shown any inclination to do any of the things it was now pledging not to do.

The ‘three no’s’ gave the Chinese the face they needed to back down.

Beijing was faring very badly in South Korean public opinion over the matter and generally losing a public relations battle with the U.S., which was playing the role of South Korea’s defender against the existential threat from North Korea. The “three no’s” gave the Chinese the face they needed to back down. President Moon, then only in his first months in office and eager to establish his own relationship with China, was able to make an official visit to Beijing late in 2017.

Japan’s period of frosty relations went back longer, to the government’s 2012 decision to purchase some of the disputed Senkaku Islands – something Beijing declared “nationalization.” China reacted by dramatically stepping up incursions into Japanese-administered waters near the islands – a practice that continues today. The thaw began in earnest in the fall of 2018 when Shinzo Abe became the first Japanese prime minister to visit China in nearly seven years. He brought 500 business executives with him and signed 53 memoranda of cooperation. Before the global COVID-19 crisis hit, Japan was planning to welcome President Xi for a return visit to Tokyo that would center around the signing of a fifth foundational diplomatic agreement with China.

Scenarios

In the near term, it is important to recognize the politics around China that are at play in Japan and South Korea. In Japan, Prime Minister Abe, in support of the Japanese business community, is working against a strong anti-China sentiment in his own base to engage with Beijing. In South Korea, President Moon represents a political tradition that is more amenable to China.

Prime Minister Abe therefore has less room to finesse security concerns, even at the best of times in Tokyo-Beijing relations. During difficult periods, he can try to accelerate the diversification of business away from China, something that has been happening on its own for many years. But it is not yet clear how much influence the government can have in changing company calculations. President Moon, by contrast, is generally much freer to pursue his own course in South Korea’s relationship with China.

Especially in the context of the coronavirus pandemic, both countries will continue to pursue rapprochement with Beijing in the near term. In the longer term, Japanese differences with China will be difficult to reconcile. Tokyo will continue to prepare for an uncertain future by improving its military capacity and drawing closer to the U.S.

South Korea will remain overwhelmingly focused on the threat from North Korea and China’s ability to help manage it. Consequently, Seoul-Beijing relations will prove more resilient in the face of provocative Chinese behavior and clear strategic designs in the region beyond the Korean Peninsula.

Over the long term, as the U.S. becomes increasingly consumed by great-power rivalry with China – with or without a solution to the North Korean threat – it will turn to Japan for greater levels of support. It will do so, in part, because that is its only option, and not just in Northeast Asia. Other countries in the Indo-Pacific region are hedging their bets on China. In Japan the U.S. will find a willing, if cautious, partner.