COP28: A ‘historic’ climate deal?

The COP28 climate conference was an exercise in pragmatism, yet still delivered significant steps in the energy transition. Success will depend on concrete follow-through.

In a nutshell

- The 28th COP summit ended with a compromise agreement

- Pledges were made to grow renewables and improve energy efficiency

- Time will tell whether nations and energy companies live up to the agreements

After two weeks of extensive negotiations, the United Nations’ 28th Conference of Parties, or COP28, concluded with the UAE Consensus – a new climate deal approved by almost 200 countries. Dr. Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, COP28 president and chief executive of ADNOC, the United Arab Emirates’ national oil company, hailed the deal as “historic.” For the first time in 28 years of summits, explicit reference was made to “transitioning away from all fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner in this critical decade to enable the world to reach net zero emissions by 2050, in keeping with the science.”

That statement narrowly avoided a failure at the summit, as participant countries were deeply divided on the wording about the future of fossil fuels – that is, coal, oil and natural gas, the main culprits behind climate change. The United States and some African, European, Pacific and Caribbean states backed a phaseout of unabated fossil fuel use. But this was strongly opposed by fossil fuel producers, notably OPEC members and especially Saudi Arabia, the world’s biggest oil exporter, as well as major consumers like China, the world’s largest energy consumer.

The economic structures of the COP28 host country, where oil is the backbone industry, may have helped shape the final agreement.

The final, more modest statement split the difference between the two camps. “Whilst we didn’t turn the page on the fossil fuel era in Dubai, this outcome is the beginning of the end,” said UN Climate Change Executive Secretary Simon Stiell in his closing speech. (Though a less enthusiastic Antonio Guterres, the UN’s secretary-general, declared that “to those who opposed a clear reference to a phaseout of fossil fuels in the COP28 text, I want to say that a fossil fuel phaseout is inevitable whether they like it or not.”)

The deal also calls on countries to accelerate “ambitious, economy-wide emission reduction targets” in their subsequent nationally determined contributions, achieve a tripling of renewable energy capacity and a doubling of energy efficiency by 2030, and more than double their adaptation financing to meet urgent and evolving needs.

Irrespective of the details and various caveats, these pledges do make COP28 historic, all the more so because they were agreed upon on the soil of one of the world’s largest oil exporters. COP28 represents a more pragmatic approach to the energy transition. It recognizes that under existing economic, social and technological conditions, addressing one of the biggest challenges humanity has faced cannot happen without complementarity between fuels and much-needed cooperation between all players.

Read more by Carole Nakhle

Asia’s energy market: The new global epicenter

A controversial host

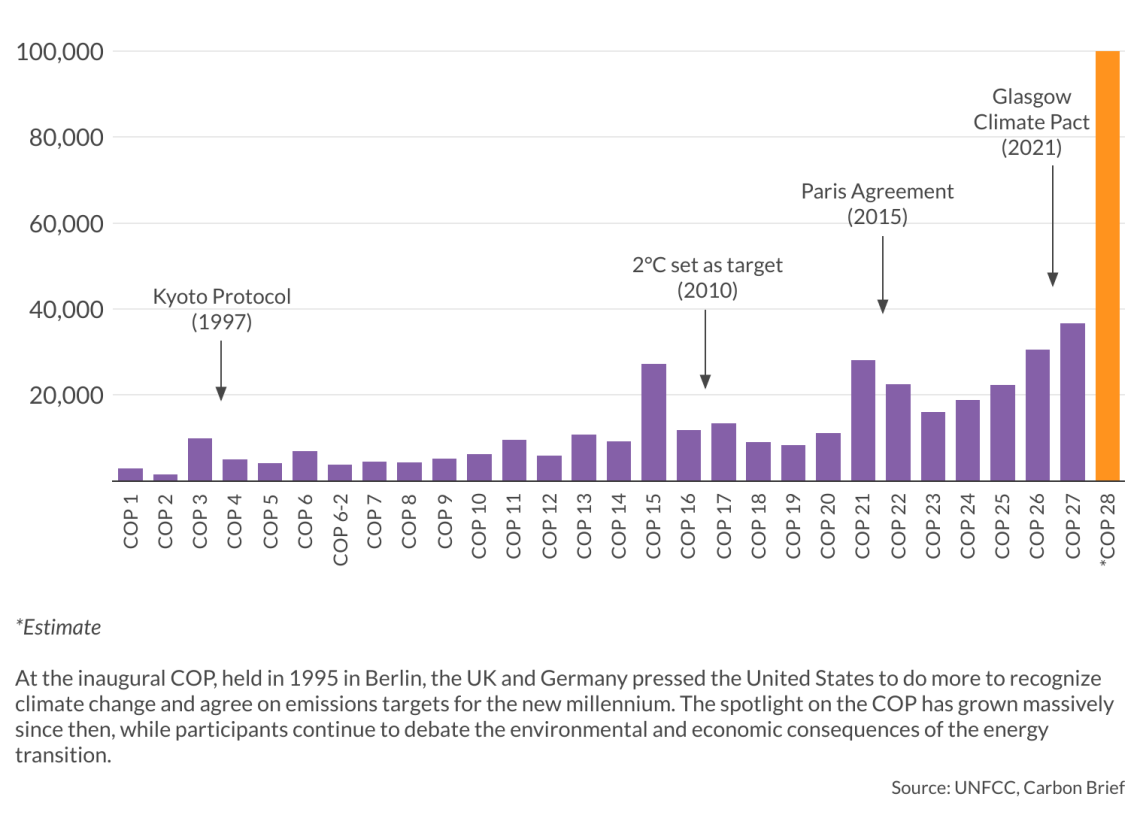

Interest in COPs has grown over the years as more countries have participated. Dignitaries and heads of state and government regularly attend alongside tens of thousands of government delegates and representatives of civil society, intergovernmental organizations, non-governmental organizations and the media. COP28 proved particularly attractive, registering the highest-ever number of attendees (estimated at around 100,000, according to Carbon Brief) and more than the last four summits combined.

The site of COP28 also intensified the spotlight. The announcements of the UAE as host country in 2021 and Dr. Al Jaber as COP28 president in January 2023 drew wide criticism from environmentalists and climate activists, while the fossil fuels industry saw it as a platform to express their objectives. Teresa Anderson, global lead on climate justice at the development charity ActionAid, condemned the summit for “being hijacked by those with opposing interests. … [W]e’re increasingly seeing fossil fuel interests taking control of the process and shaping it to meet their own needs.” One report claimed to have tallied over 2,400 fossil fuel representatives at COP28, almost outnumbering representatives from all individual country delegations.

However, the UAE is not the first oil and gas producer to host a COP. Past examples include the Netherlands (COP6, 2000), Canada (COP11, 2005), the United Kingdom (COP26, 2021), Egypt (COP27, 2022), and then-OPEC members Indonesia (COP13, 2007) and Qatar (COP18, 2012). Nor was this the first time an oil official helmed the conference. Abdullah bin Hamad Al-Attiyah, president of COP18, had served as Qatar’s minister of energy and industry and as head of Qatar Petroleum (now Qatar Energy).

Facts & figures

The economic structures of the COP28 host country – where oil is the backbone industry – may have helped shape the final UAE Consensus, particularly in the attempt to balance the divergent needs of various players, including those dependent on fossil fuel revenues.

Early wins

The first significant achievement at COP28 was a multinational agreement on the mechanics of the Loss and Damage Fund, which was agreed to at COP27 but with no clear framework over its structure, who should pay into it or which countries would benefit.

The idea of a global fund to provide financial assistance for developing countries most affected by climate change is not new; it was initially put forward by the small island nation of Vanuatu, which raised the question of who should foot the bill for climate catastrophes. At COP28, it was agreed that the World Bank would host the fund for four years and would target small island states and the least developed countries. Nineteen nations made commitments toward the fund, totaling $792 million.

Also in the early days of the summit, more than 20 countries, including the U.S., UAE and the United Kingdom, launched the Declaration to Triple Nuclear Energy – recognizing the critical role of nuclear energy in achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and limiting global warming to an increase of 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels (per the 2015 Paris Agreement goals). The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) described the initiative as “nothing short of a historic milestone and a reflection of how much perspectives have changed.” Notably, the UAE is the only Arab country with an operational nuclear power plant.

Success criteria

Ahead of COP28, the International Energy Agency (IEA) outlined five critical objectives against which the outcomes of the meeting should be measured:

- A tripling of global renewable power capacity

- A doubling of the rate of energy efficiency improvements

- Commitments by the fossil fuel industry, especially oil and gas companies, to align their activities with the Paris Agreement, starting with 75 percent cuts to operational methane emissions

- Commitments to ensuring an orderly decline in the use of fossil fuels, including an end to new approvals of unabated coal-fired power plants

- The establishment of large-scale financing mechanisms to triple clean energy investment in emerging and developing economies

COP28 delivered on the first two criteria, which are those that were assigned a clear, tangible deadline in the ultimate agreements. With respect to the third point, the COP28 Presidency and Saudi Arabia launched the Oil and Gas Decarbonization Charter (OGDC) on December 2. It was joined by 50 oil and gas companies representing over 40 percent of global oil production, and with national oil companies representing a majority of signatories – the largest-ever number to commit to a decarbonization initiative. The charter formalizes industry calls for oil and gas companies to reach net zero by 2050, aim for near-zero upstream methane emissions by 2030, and achieve zero routine flaring by 2030.

COP28 also met the fourth IEA metric, though it eschewed terms such as “phaseout” or “phasedown,” except in the context of unabated coal power. (The agreement refers to “accelerating efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power,” meaning coal burning without carbon capture and storage.)

Some partial breakthroughs were achieved on the final objective. For instance, a Global Climate Finance Framework was launched with a focus on access to finance, but it was only signed by 13 countries (including the U.S., India, France and the UAE). While the declaration recognizes the need to invest some $5-7 trillion annually in greening the global economy by 2030, it acknowledges that a significant portion of the financing needed for climate action will come from domestic savings and efficient fiscal incentives, in addition to the important role of private sector finance and carbon markets. As Fatih Birol, executive director of the IEA, stated: “Pleased to see most IEA pillars reflected, though greater efforts are needed on finance for developing economies.”

Facts & figures

- The Conference of Parties (COP) is an annual climate summit where UN member states gather to assess progress on climate change and develop plans for action. It is held under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC), a cross-national body whose goals are to acknowledge the climate change problem and stabilize greenhouse gas emissions.

- Member countries have equal voting power, regardless of their size, and decisions are consensus-based.

- Each year, a different country hosts the COP and assumes its presidency (with 2020 an exception due to Covid-19).

- The first COP meeting was held in Berlin, Germany, in March 1995.

- The oil sector accounts for a quarter of the UAE’s gross domestic product (GDP), 60 percent of government revenues and 51 percent of merchandise exports.

Stepping forward

COP28 was not the climate summit that many may have hoped for. Several objections can be made, particularly over the lack of tangible targets and the widespread use of general or vague terminology that can be subject to different interpretations. For example, the deal recognizes that “transitional fuels” can play a role in facilitating the energy transition while ensuring energy security, but it does not define what constitutes a transitional fuel.

However, on balance, the meeting was an important step forward. Its debates and outcomes reflect the dynamics of the world we live in, competing perspectives and priorities, and the complex nature of the energy transition today. COP28 acknowledged the underlying conditions each country faces while making room for flexibility in achieving the greening of the world’s energy mix. It called on parties to “contribute to the following global efforts, in a nationally determined manner, taking into account the Paris Agreement and their different national circumstances, pathways and approaches.”

Some see weakness in such a statement; others see pragmatism. But in the end, the success of any climate gathering rests not in promises, no matter how bold, but in action and delivery.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.