Costa Rica: Challenges to stability mount

Amid the Covid-19 crisis, Costa Rica faces a slowing economy, political fragmentation and violence associated with drug trafficking. Now, measures to contain the pandemic are taking a massive economic toll, smothering its lucrative tourism sector.

In a nutshell

- Costa Rica’s politics have become less stable

- Its economy is slowing and citizen security worsening

- Measures to contain the pandemic have hit hard

For years, Costa Rica has found itself grouped with Chile and Uruguay as one of the three strongest democracies in Latin America. It has solid institutions, a well-developed social welfare system, a stable economy and a citizenry that is proud of its democratic culture, particularly compared with its neighbors.

Extraordinarily, Costa Rica has no permanent standing army. The country has used its soft power to take the lead in regional affairs and demonstrate its geopolitical clout in global institutions. In the 1980s it was instrumental in ending the civil strife tearing apart El Salvador and Guatemala, helping President Oscar Arias win a Nobel Peace Prize in 1987. In the early 2000s, it convinced the United States and other countries in the region to join a free trade agreement (CAFTA-DR). More recently, one of its senior diplomats, Christiana Figueres, led the drive for the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015.

As with Chile and Uruguay, however, signs have appeared that Costa Rica is not immune to the difficulties that are troubling its neighbors. Economic growth has flattened, the quality of employment is deteriorating and the Gini coefficient (which measures inequality in a society) is rising. The two main political parties have fragmented, making governance more complicated. The drug trafficking that has overwhelmed the Northern Triangle countries – El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras – is seeping into the country. Its system is under increasing stress: more than 100,000 Nicaraguans fleeing the repressive regime of President Daniel Ortega have entered the country in the past year, and the COVID-19 pandemic has hit the economy hard.

Political situation

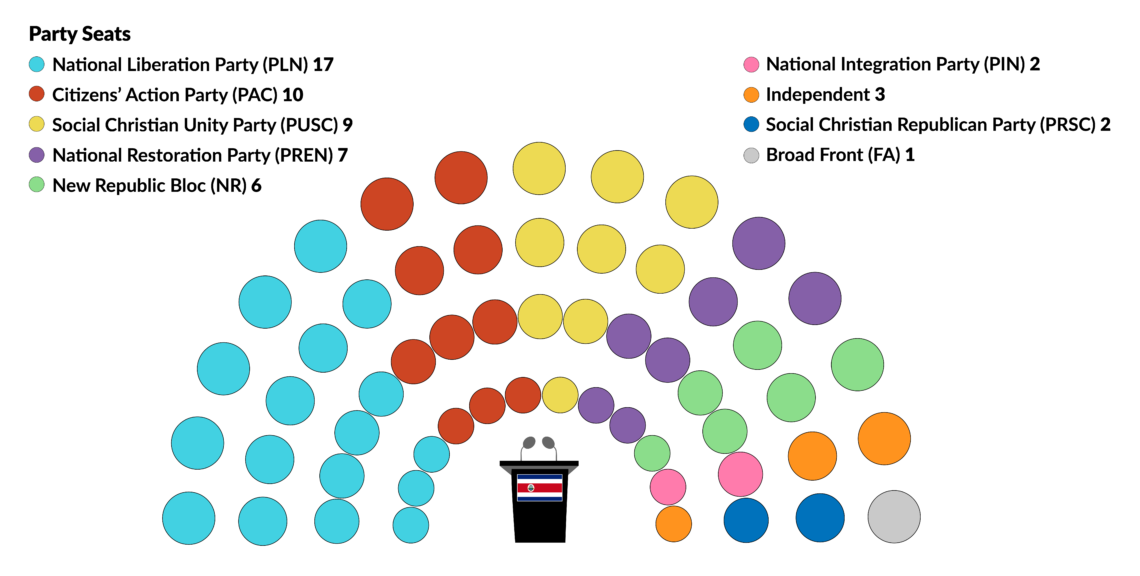

Until recently, the political scene in Costa Rica was dominated by two parties, the left-of-center National Liberation (Partido de Liberacion Nacional, or PLN), and the center-right Social Christian Party (Partido Unidad Social Cristiana, or PUSC). Then, both suffered splits. The group that splintered from the PLN, known as the Citizens’ Action (Partido Accion Ciudadana, or PAC), nominated Luis Guillermo Solis for the 2014 presidential election, which he won. The conservatives also split, with the PUSC’s spinoff called the National Integration Party (Partido Integracion Nacional or PIN).

Because of his weak position, the president has had difficulty getting fiscal discipline measures through the congress.

Current President Carlos Alvarado Quesada, also of the PAC, barely won the 2018 election, beating Fabricio Alvarado (his fifth-cousin) from the Christian National Restoration Party (Partido Restauracion Nacional, or PRN). The elections for the legislature were also polarized and fragmented. The PAC has only 10 of the 57 seats in the legislature. The biggest bloc is the PLN, with 17 seats and tends to back the president.

On the other side, however, are the PRN, with 14 seats, the PUSC with nine, and two other evangelical parties with six seats among them. These groups could form a razor-thin majority if they ever agreed to do so. Fortunately for President Alvarado, that appears unlikely.

Facts & figures

Because of his weak position, the president has had difficulty getting fiscal discipline measures through the congress. The opposition objects to his proposed cuts in social benefits.

President Alvarado faces two main political threats. The first is mass protests, which, though unusual for Costa Rica, began occurring last year. The second is the Justice Department’s investigations into alleged corruption. The protests have occurred in various cities and have included student groups and transport unions. Three ex-presidents face corruption allegations: Mr. Arias, Mr. Solis and Laura Chinchilla.

The Justice Department investigated President Alvarado over suspicions that a data-analysis unit run by his administration violated personal privacy laws. Prosecutors even raided the president’s office in February. Several cabinet members resigned. The allegations have eroded public confidence in the government.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has given President Alvarado some respite from these investigations. He has moved rapidly to deal with the epidemic through executive orders enhancing social benefits and by regularly providing the public with information about the epidemic. Opinion polls show that most of the public supports the measures the government is taking.

Economy and citizen security

Costa Rica’s economy was doing relatively well until growth began to slow three years ago. Along with a strong tourism industry, the country’s reputation for stability and the rule of law, and a small but vibrant technology sector, had produced a broad middle class. The United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean now predicts that the economy will decline by as much as 2 percent this year, taking the impact of the pandemic into account.

Facts & figures

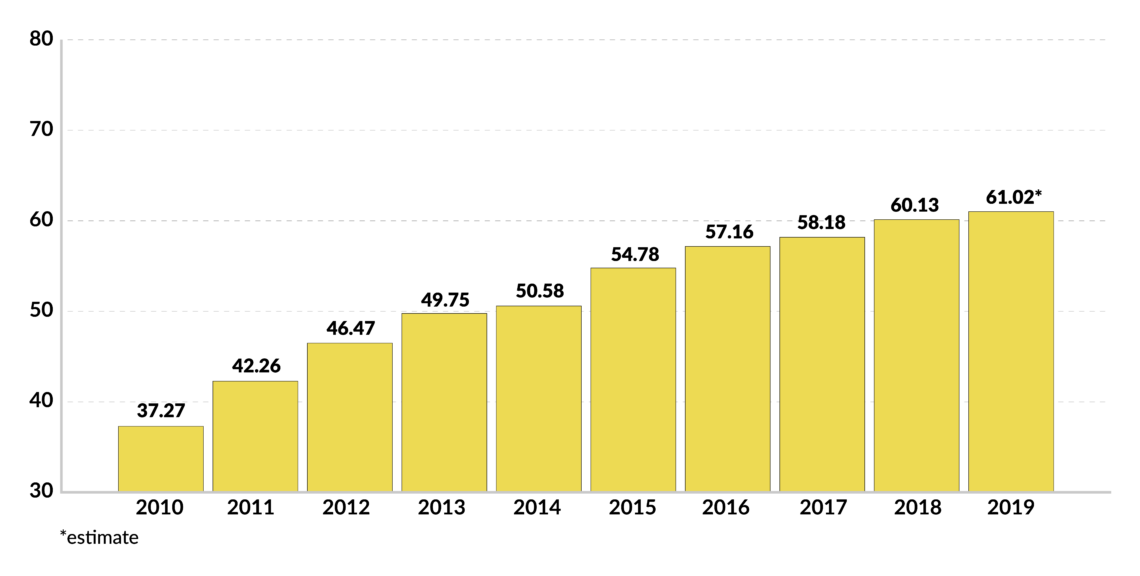

To maintain the country’s generous social welfare program, the state has increased borrowing: the external debt has more than doubled since 2010 and is predicted to reach 60 percent of gross domestic product by the end of this year. The slowdown has affected virtually all the biggest contributors to the economy, including agriculture, forestry, mining, manufacturing and construction, among others. Tourism had been holding up until the outbreak of COVID-19. Now that industry is taking a huge hit.

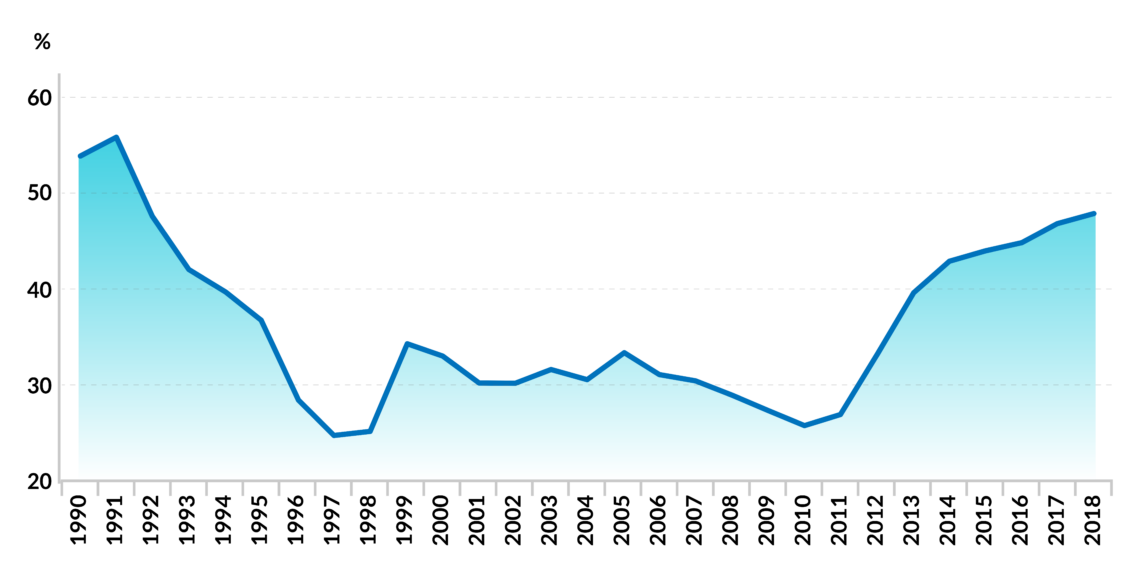

The sluggish economy has led to a deterioration in consumer demand and in retail lending, which has been central to Costa Ricans’ way of life. Unemployment has reached 12 percent, while the quality of employment has deteriorated. This syndrome affects the most vulnerable in the society, especially those outside the major cities. The rising Gini coefficient reflects the slow decline in the quality of life. Through it all, the government has maintained sufficient fiscal stability to keep the value of the currency, the colon, stable against the dollar. Costa Rica has one of the lowest inflation rates in the region.

Facts & figures

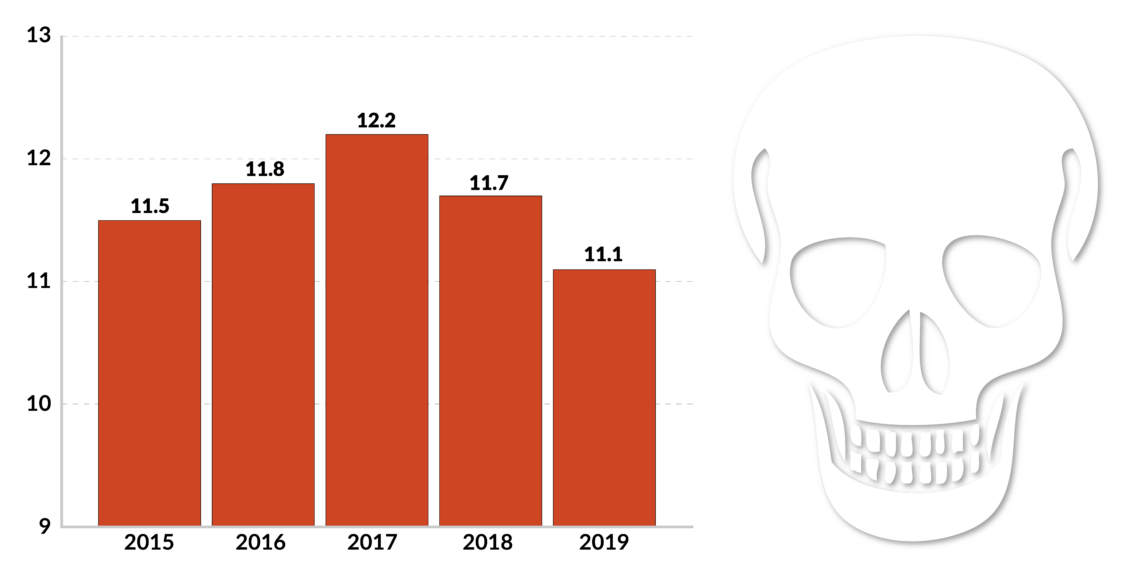

For many years, Costa Rica has been one of the safest countries in all of Latin America. Over the past decade, that sense of security has eroded as international drug trafficking and the criminality associated with it, especially violence, have increased. Even though the homicide rate has declined over the past two years and remains much lower than in the Northern Triangle, recent polling indicates that there is a sense of growing insecurity.

COVID-19

A bright spot in Costa Rica’s otherwise murky horizon is that the country has one of the most robust public health systems in the region. Experts consider it one of the best in the world in terms of quality, cost and coverage. This is the result of consistently high investment in healthcare, both private and public.

To its credit, the Alvarado government was the first in Central America to report a case of the virus. From the very beginning, the government began to take safety measures. Along with calling for social distancing, imposing stay-at-home orders and closing public spaces, the government created an emergency committee to monitor the situation. The president and the health minister regularly appear on television to offer updates.

The government has introduced a plan to supplement salaries and provide extra funds for pensioners.

The government has introduced a plan to supplement salaries and provide extra funds for pensioners. It has also established a special capital fund for those whose workday has been limited by the quarantine. So far, the population has responded positively, though social distancing and self-quarantine are difficult for those in precarious housing or where access to water is severely limited.

Facts & figures

Even with these efforts, the pandemic will cause severe economic pain in the coming months. Important industries like tourism and retail will suffer the most, but the contraction will hit all sectors. In the long run, the measures the government is taking now will raise the debt load – both public and private – so that even after the cruelest effects of the pandemic have passed, there will be costs associated with it for years.

Scenarios

So far, President Alvarado has shown constructive leadership in dealing with the pandemic and its economic impact. In this, of course, he is supported by one of the most robust health systems in Latin America. Because of this infrastructure and the government’s quick reaction, Costa Rica is likely to suffer less than its neighbors.

The mechanisms that President Alvarado has put in place to communicate with the population and address the economic effects will increase support for the government through the next three to six months of the crisis. It will receive a further boost since the traditional parties – PLN and USC – have agreed to suspend their attacks on the administration. Most parties support the economic package.

A less likely scenario is that President Alvarado would not be able to maintain his leadership and the public health system collapses. That would lead to a period of political instability and economic stagnation.

Once the spread of the disease begins to slow, the political situation will become more complicated. Then, President Alvarado will be faced with an economy even weaker than it was before the crisis. There will be no assurances that the external environment, especially Chinese investment, will provide the stimulus the economy needs to grow.

Two factors will determine the pace of recovery after the pandemic has eased: Chinese eagerness to return to investment projects in Costa Rica and how quickly tourists from the U.S., Canada and Europe can return to enjoying the country’s beaches and national parks.

The latter will partly depend on how quickly those places begin allowing international travel. The process should begin next month and would immediately have a positive impact on Costa Rica.