Stable Uruguay has developed-nation aspirations

The citizens of middle-income Uruguay want living standards typical of more developed countries, and have elected Luis Lacalle Pou as their new president to achieve that goal. Radical politicians on both the right and the left could hamstring his government.

In a nutshell

- President-elect Luis Lacalle Pou represents the center-right

- In recent years, crime in Uruguay has risen and the economy slowed

- Passing legislation may require the new president to work with hardliners

Many years ago, when I was working in Argentina for some months, the country was going through one of the crises that have marked its history for the past several decades. As I mentioned in a recent report on that country, the current crisis has many of the same characteristics – multiple exchange rates, high inflation, constant efforts to exchange pesos for dollars and to get the dollars out of the country.

To keep ahead of the galloping inflation at that time, I sold my U.S. dollar checks in the well-guarded back office of an exchange company. Those checks always came back endorsed by a bank in Uruguay. One day, I took the ferry across the River Plate to Montevideo, the capital of Uruguay, and found myself in another world: calm, quiet, a bit run-down but with a stable exchange rate and a remarkably calm populace. In conversation with a friend who held an important position in the local government, I suggested that the future of Uruguay could be as the Singapore of Latin America. He laughed at me.

Today, Uruguay still distinguishes itself from the rest of the region by its stability. Montevideo, the capital, still looks a bit run-down. On the other hand, the skyscrapers and beaches in Punta del Este are anything but neglected, as they represent safe havens for Brazilians and Argentines who want to get their money out of their own countries and park it somewhere. It isn’t Singapore, yet it is what I had in mind for Uruguay four decades ago.

Factional politics

Today, Uruguay also stands out from the rest of South America in that there have been no protests in the streets. Nevertheless, it would be wrong to conclude that the country is without its problems. In the recent elections in October 2019 (for the legislature and the first round for president) and November (the second round for president), the voters expressed their discontent with the incumbent center-left government that had been in power for 15 years, the Broad Front (in Spanish Frente Amplio, or FA) by electing a center-right government.

Luis Lacalle Pou promised to be tougher on crime, friendlier to the private sector and to reform the bloated public sector.

The winning candidate was Luis Lacalle Pou of the National Party. He promised to be tougher on crime, friendlier to the private sector and to reform the bloated public sector, which not only weighs heavily on the national budget, but also complicates business activity.

The problems facing President-elect Lacalle Pou when he takes office on March 1, 2020, are manifold. To begin with, he won the election by forming a “multicolor” coalition with four other parties on the right: the Colorado, Open Cabildo, the Independent Party and Party of the People. Open Cabildo (Cabildo Abierto in Spanish, roughly translating as “town hall meeting”) is a small, new party led by a former chief of the country’s army, Carlos Manini Rios, who is noted for his radical statements.

Facts & figures

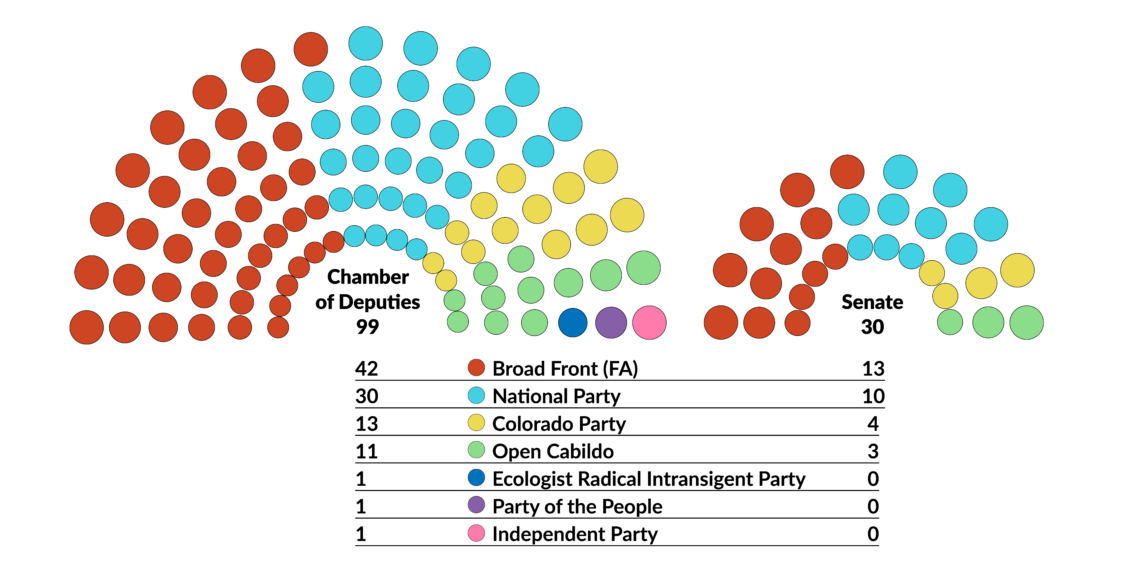

Without the votes Mr. Manini Rios commands and the votes of the Colorado Party in the legislature, Mr. Lacalle Pou will not be able to govern. His party has 10 seats of the 30 total in the Senate. The Colorado Party has four and Open Cabildo has three, while the opposition FA has 13. Of the 99 total seats in the lower house, the Chamber of Deputies, the National Party has 30, Colorado has 13, and Cabildo Abierto has 11. The three other tiny parties – the Party of the People, the Independence Party and the Ecology Party – have one seat each. While the smaller parties have few votes in the legislature, their presence and positions will be noted in the president’s cabinet and elsewhere in the executive branch.

The FA opposition is itself split into fragments. The three main groups are Tupamaros, Communists and Socialists, which control most, but not all, of the opposition seats. Danilo Astori, a respected, moderate voice, has a seat in the Senate. Mr. Astori served twice as economy minister and as vice president under former President Jose Mujica (2010-2015). Together, the various opposition groups – all linked to the FA – represent 42 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 13 in the Senate. There are elements that have become radicalized over the past few years. Many of them are unhappy with the outgoing FA government, and they are unlikely to cooperate with the new government in passing legislation.

Economic difficulties

Mr. Lacalle Pou’s other big challenge is that the country’s economy scarcely grew in 2019 and 2020 is not looking much better: its gross domestic product (GDP) is forecast to grow by barely 1 percent. The fiscal deficit is at 5 percent of GDP. The president-elect has said that as soon as he takes office, he will present Congress with an emergency plan to deal with these issues.

Uruguay is essentially an exporter of agricultural commodities, for which international market prices have held flat over the past few years. They are about a third lower than their peak at the beginning of the last decade, a peak which funded the FA’s generous social programs.

If commodity prices do not improve, it will be hard to cover the deficit, much less maintain the country’s welfare programs.

In the short term, the global economy appears to be slowing down, while the trade conflict between the United States and China complicates the situation in the international market. If commodity prices do not improve and economic activity does not increase, it will be hard to find the money to cover the deficit, much less maintain the country’s welfare programs. Those programs are among the most generous in Latin America and most Uruguayans take them for granted.

Facts & figures

Under current circumstances, the social welfare system in not sustainable. President-elect Lacalle Pou has said he wants to reform the public sector. This may save the country some money, but it will also open a Pandora’s box of political complications. He also wants to reform the pension system. As anyone in Europe or in Brazil can tell you, that will not be easy.

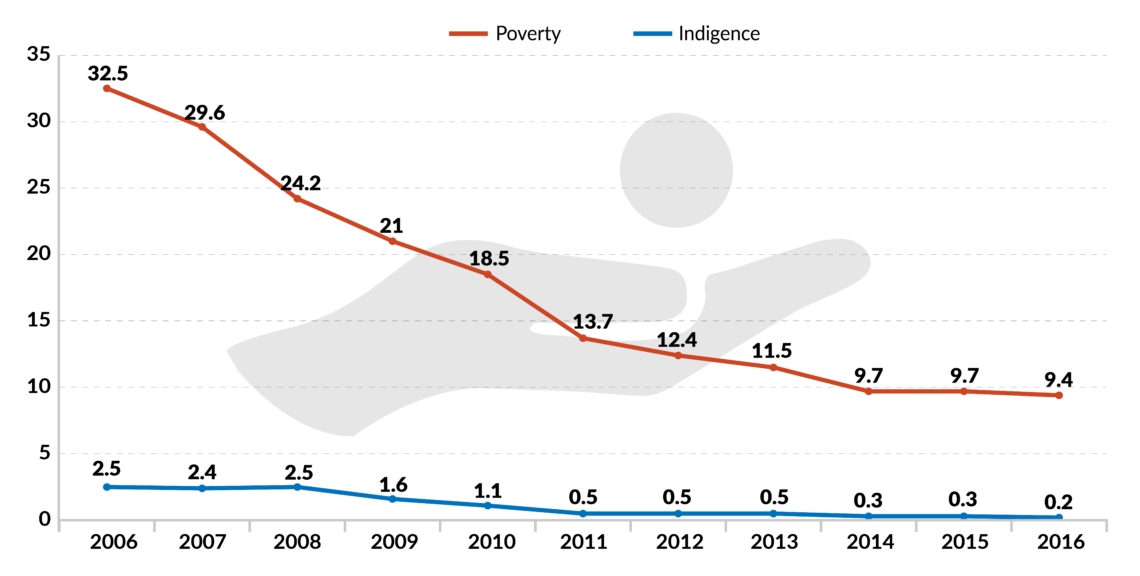

Uruguayans are accustomed to a rate of inflation around 7 to 8 percent, much lower than their neighbors in Argentina and Brazil. They are also used to a declining poverty rate, already among the lowest in the hemisphere, and the virtual nonexistence of extreme poverty. The reduction of poverty and indigence is one of the FA governments’ great successes. Mr. Lacalle Pou will have to consider this as he tries to make the economy more market-friendly.

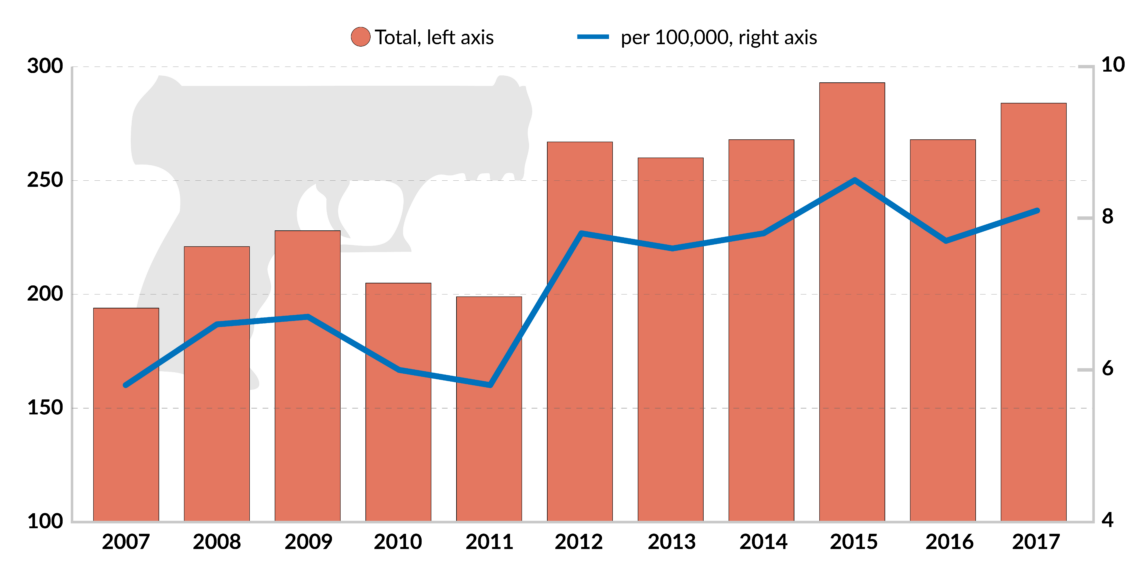

Rising crime

One of Mr. Lacalle Pou’s strongest campaign arguments was that he would deal with the growing sense of citizen insecurity. This was General Manini Rios’s main argument and the president-elect will have to address the issue. Citizen insecurity in Uruguay is an anomaly in comparison to the rest of Latin America, where homicide rates have risen as high as 100 per 100,000, compared to the 8 per 100,000 in Uruguay. The problem in Uruguay is that for several decades – a lifetime for most voters – the rate was in the range of 5 or 6 per 100,000. So the homicide rate in Uruguay has jumped by a third over the past decade. That has caught the voters’ attention.

Facts & figures

It didn’t help the FA in the last elections that in August, there was a massive drug bust of 4.6 tons of cocaine in the Hamburg harbor on a vessel that had come from Montevideo. A similar incident took place in Montevideo in December, not long after the second round of the presidential election. The six tons captured in the second bust were said to be worth more than $1 billion on the black market. Uruguay may have become a major transit area for cocaine on its way to Europe.

The chief political problem in dealing with this sense of insecurity is that the more conservative elements in the new government will want to attack the problem with more police and harsher penalties, while the FA, especially its more radical elements, believe that the way to deal with crime is by addressing what they consider its causes: poverty and other social indignities.

Improving competitiveness

In the long term, growth and development in Uruguay will depend on improving the economy’s competitiveness: its ability to sustainably generate high levels of income and employment with equity and inclusion. Uruguay certainly has stable institutions, the best level of equality in Latin America and a relatively well-educated workforce. However, the failed efforts of successive administrations to reform the public sector have had a profound negative impact on entrepreneurial behavior, especially foreign direct investment bringing innovation, and have also had the effect of linking production to the most traditional sectors of the economy, such as agriculture, tourism, and more recently, paper pulp, since these sectors are competitive enough to tolerate an inefficient public sector.

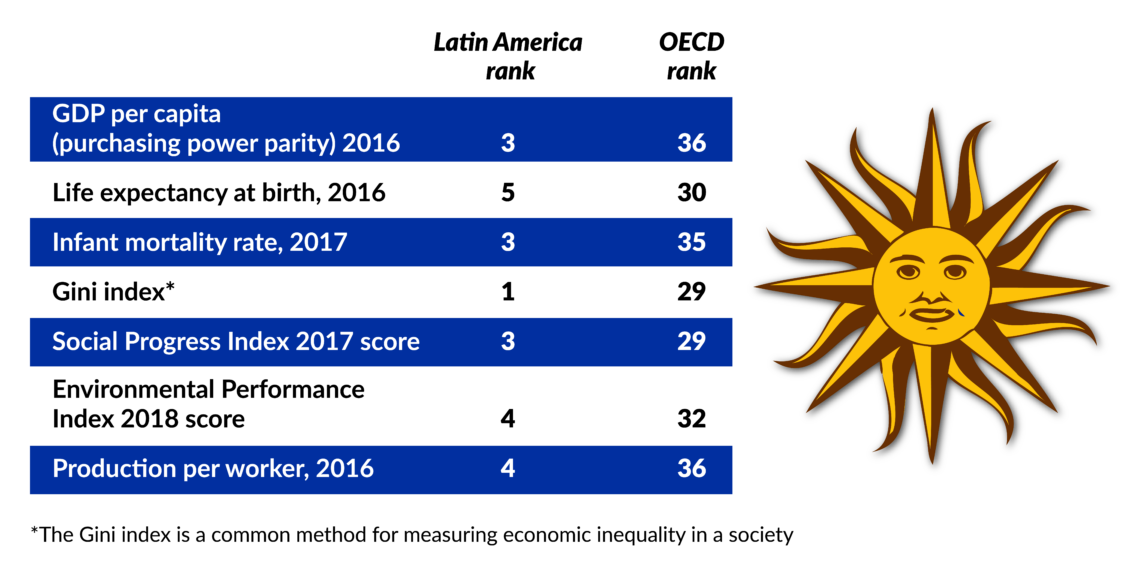

Facts & figures

In a recent study by the Catholic University of Uruguay, six macroeconomic indicators were used to evaluate the competitiveness of an economy: inflation rate, fiscal deficit, unemployment, sustainability of the public debt, volatility of the real exchange rate, and the ability to preserve the “investment grade” qualification for its public debt. According to the study, the first four have deteriorated over the past decade. If the volatility of the real exchange rate were to follow, the situation will eventually have a negative impact on the nation’s investment ranking.

That would pitch Uruguay into a vicious circle hindering its ability to modernize, diversify and compete in the international market. It is modest consolation to realize that Uruguay actually measures up well with other countries in the region. When it is compared with other countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), however, it does not fare as well.

Mr. Lacalle Pou’s challenge is to satisfy social demands typical of developed countries in a still-developing, middle-income country.

Scenarios

Over the next three to six months, the new Lacalle Pou government will present its emergency plan to Congress. In the most likely scenario, it will pass, though after a heated debate in which there might be some modifications that lessen the impact of austerity on welfare programs in the short term. The legislation will not have an immediate effect on the economy. Instead, it will probably continue to plod along at its current, low rate of growth, at least until the second half of the year.

It is also likely that the new government will attempt to demonstrate its resolve through some measures designed to improve the sense of citizen security, such as increased police presence in the streets of Montevideo and other cities.

How quickly the new government in Argentina brings its economy into order will affect the Lacalle Pou government. It is also likely that the new government, recognizing the importance of making Uruguay more competitive in the international market, will do everything it can to preserve the institutional stability of the country even during a period of a sluggish economy. This leaves Mr. Lacalle Pou with the same long-term challenge as that faced by previous FA governments: how to satisfy social demands typical of developed countries in a still-developing, middle-income country.

The less likely scenario is that Mr. Manini Rios will prove to be an uncontrollable and unreliable coalition partner. If that happens, Mr. Lacalle Pou will find it extremely difficult to get his economic reforms through the legislature without some adjustments designed to placate Open Cabildo. That will embolden the opposition to block his efforts at reform and extend the period of delicate fiscal instability that proved so debilitating to the FA government in its last few years in power.