Covid-19: The impact on East Asia

The Covid-19 crisis has reduced China’s economic clout in Asia. Many states will look to diversify their economies away from the aspiring regional hegemon. It could provide an opportunity for Japan, which could step into the vacuum as an influential regional power.

In a nutshell

- The coronavirus crisis has revealed flaws in the Chinese system

- The high costs could force Beijing to pull back internationally

- Japan could benefit from increased clout and investment

This is the first in a new GIS series on the consequences of the COVID-19 crisis. It looks beyond the short-term impact of the pandemic, instead examining the strategic geopolitical and economic effects that will inevitably be felt further in the future.

Whatever the short-term impacts of the coronavirus crisis are on the global and national economies, we can already see some long-term effects. Many of the most important among them are geopolitical.

First, the coronavirus crisis has led to a substantial loss of face and prestige for the People’s Republic of China. While many observers are impressed by China’s efforts to contain and overcome this health crisis, the Chinese political system failed its people, particularly at the beginning of the crisis. As with the 2002-2004 SARS outbreak, the initial response of the authorities to the new coronavirus in December 2019 was woefully inadequate and harmful. Systemic failures contributed to the spread of the disease, leaving the country with enormous human and economic costs.

The rapid spread and high death toll exposed the inadequacies of the Chinese health system and reminded the world that for the vast majority of its population, the People’s Republic is still a developing country. The crisis also revealed severe deficiencies. Though a huge population can be an asset, when a crisis hits, it can become a liability.

The world has seen that China is not the almighty superpower many of its new leaders had claimed it is.

Most importantly, the quick spread of the virus, the necessary lockdown of millions of people and the country’s unprepared leadership were a humiliation that will not be easily forgotten. The world has seen that China is not the almighty superpower many of its new leaders had claimed it is.

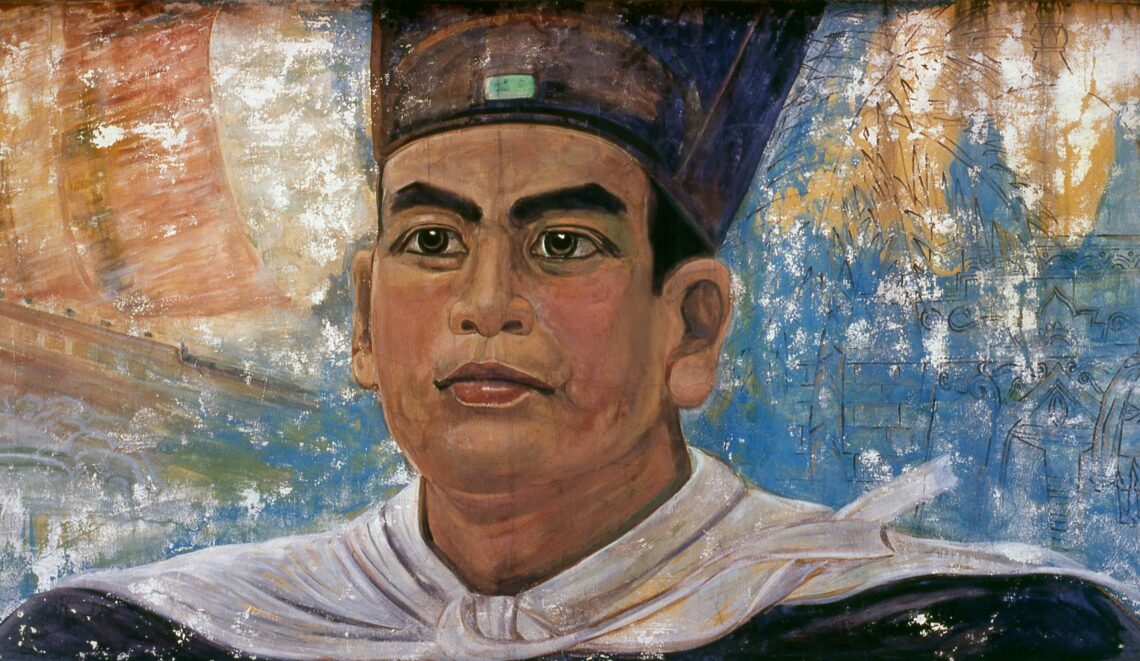

A Zheng He moment?

The great Chinese reformer Deng Xiaoping had admonished his countrymen to be pragmatic and cautious. His slogans were, “bide your time” and “hide your strength.” In recent times, most notably since President Xi Jinping has become the all-powerful leader of the country, China has been showing the world a bolder face – expanding its military, economic and political power.

The new ambitions, manifest in gigantic projects such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) as well as costly investments in overseas, require vast sums of money. Already before the outbreak of the coronavirus, there were indications of “imperial overstretch,” be it in political spats with BRI project host countries or mismanagement and financial complications.

It is still unclear how much economic damage the crisis has done to the Chinese economy. The price tag will certainly be substantial. Beijing will need huge sums of money to assist the companies, communities and individuals that have suffered from the financial fallout of the crisis.

The “Mandate of Heaven” – the ancient justification for the rule of a leader over China – which supposedly predisposes the Communist Party of China to rule the country, rests on robust economic growth, a substantial increase in prosperity and competent, efficient governance. A prolonged economic downturn and severe social distress could lead to a systemic collapse. The Chinese government is fully aware of this threat, which is why it will use all of the tools at its disposal – financial, social and political – to keep the country under control.

The Communist Party is not a monolith. It contains various groups with varying philosophies. One group is strongly nationalist: its members will press the leadership to focus on the welfare of the people and the military strength of the country. They will demand new priorities for the usage of government finances. They will find support for their position that China should not squander valuable financial means on overseas adventures, most notably in Africa.

In the early years of the Ming Dynasty, from 1405 onward, the Middle Kingdom sent several huge naval fleets under the leadership of admiral Zheng He into the Indian Ocean. The expeditions did not lead to the establishment of Chinese colonies. They served to spread the fame and prestige of China and its “Son of Heaven” on the imperial throne. Suddenly, in 1433, the expeditions stopped. There are several theories as to why. One is that they had simply become too expensive and the money spent on them did not bring the desired rewards.

Only time will tell whether the coronavirus crisis will eventually lead to a Zheng He moment. Certainly, China is too intertwined with the global economy to withdraw into a protectionist shell. The question of how scarce financial resources will be allocated in the future, however, remains wide open.

Japan steps in

All this leads us to the question of how geopolitics in East Asia will play out over the next several years. Currently, Sino-Japanese relations are improving. China, which has to focus on the enormous task of overcoming the socioeconomic impact of the crisis, has no interest in increased instability on the Korean Peninsula. Beijing may even demand more obedience from Pyongyang in return for the food and energy supplies it provides North Korea, which is once again in the midst of a hunger crisis.

Japan and South Korea, in particular, have been shaken by the fragility of supply chains. Once the present crisis is behind us, they will have to reconsider their dependence on China. Diversification will become the new watchword. Relying so much on trade with China, which over the past 30 years had become the factory of the world, was easy and profitable. Yet the present crisis has awakened the world to the danger of focusing too much on one producer and one market.

Japan and South Korea will have to reconsider their dependence on China. Diversification will be the new watchword.

The geopolitical implications of these shifts will make Japan reconsider its engagement overseas. As could be seen in recent years, the country’s shrinking and aging population has already pushed major Japanese companies to search for new markets and investment opportunities abroad. Southeast Asia and India offer huge markets and substantial demands for catching up in infrastructure. Further afield, Africa and Latin America could enter into Japan’s focus. In all these areas, Japan can profit from China having less means at its disposal for further overseas expansion, at least in the foreseeable future.

This scenario also implies significant security challenges. Japanese strategists see two possible long-term reactions within China to this new situation. On one hand, the nationalists’ influence in China could significantly increase. On the other, the country could turn inward. Both developments would hurt Japan. With a rare state visit of President Xi Jinping to Japan in the offing, it is unlikely that Beijing will take any extreme steps for now.

Japan is almost certainly already in a recession – after one quarter of negative economic growth at the end of 2019, it is likely to experience more shrinkage in the first quarter of 2020, especially with the coronavirus crisis affecting the global economy. Nevertheless, it will still have a major role to play in the global recovery, which will depend on four pillars: the United States, China, the European Union and Japan.

The Bank of Japan has already announced that it will do everything in its power to temper the effects of the crisis. In this endeavor, it faces two major difficulties. First, historically low interest rates limit the bank’s scope for action. Second, the dip into negative growth in the last quarter of 2019 was largely caused by domestic factors, most notably by the increase in the consumption tax. The Japanese economy had entered the coronavirus crisis in an already weakened state.

Disengagement

Looking beyond the immediate future, Japan has to face a new scenario as a result of the rapid disentanglement of the U.S. and Chinese economies. This process is not a temporary bump in the road caused by the Trump administration’s ad hoc decisions in the U.S.-China trade dispute. Whether President Donald Trump wins a second term or not, fundamental changes have taken place in the relations between the world’s two largest economies.

The exodus of American companies from mainland China will have gained additional momentum through the disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic. The shock of highly vulnerable supply chains is bound to hurt, as more and more decision makers worry that China will again be subject to large-scale health emergencies.

Japan has to face a new scenario as a result of the rapid disentanglement of the U.S. and Chinese economies.

The redirection of U.S. corporate involvement away from China may not be as dramatic as it currently looks. But it will be substantial, and it will have geopolitical implications for Japan. With China becoming less attractive for U.S. businesses, Japan could gain more attention in Washington. American companies will be looking for more opportunities in Japan, not necessarily in its domestic market, but in its technological prowess and its substantial innovative capacities.

The coronavirus crisis has revealed serious flaws in the Chinese economy and China’s political and administrative structure, increasing its risk profile and enhancing Japan’s image as a reliable alternative. While the production of cheap goods has already begun to move to countries like Vietnam, Myanmar and Bangladesh, Japan will be attractive for high-tech industries, artificial intelligence, robotics and life sciences. In all of these areas, the U.S. and other industrialized nations are already wary of the security threat posed by China gaining a dominant position in the market.