COVID-19 and the future of central banking

As the covid crisis freezes large swaths of the economy, the world’s three most important central banks find themselves under tremendous political pressure to flood the markets with easy money again. Their approaches may prove significantly different.

In a nutshell

- Central banks are devising responses to economic dislocations triggered by Covid

- China may be tempted to use the emergency to cull its economy’s weak sectors

- In the U.S., the Fed meekly focuses on trying to prevent recession in an election year

The new variety of coronavirus, code-named COVID-19, has taken practically everybody by surprise. Financial markets have seen massive sell-offs, as is usual at times of great uncertainty. Policymakers have generally responded too late – but wasted no time in advocating more debt-financed government expenditure. The purpose was, of course, to restart the economy and compensate for the economic losses associated with the restrictive measures adopted during the past few weeks. Once again, the European Union has highlighted its limitations by not being able to agree on a common vision. Ultimately, despite their considerable shortcomings, the Chinese have taken the lead and the world follows.

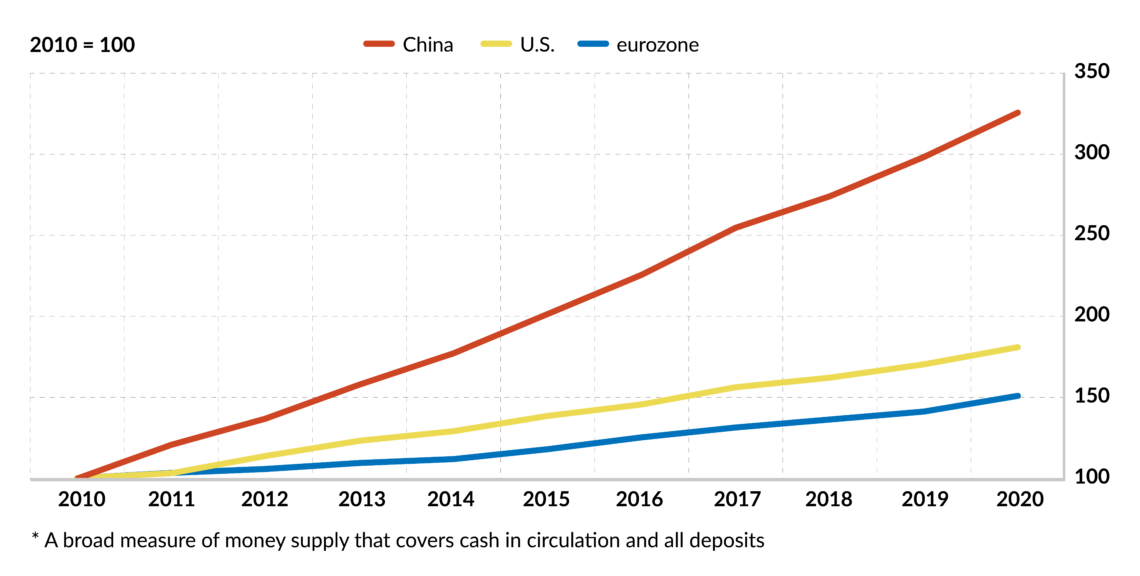

The pandemic brought other surprises as well, with one related to the role of central banking and monetary policy. In mid-February 2020, public opinion, politicians and financial investors were persuaded that central banks would step in and do “whatever it takes” (to utilize former European Central Bank President Mario Draghi’s famous phrase) to bring major economies back on track during a crisis. The belief was not a figment of the masses’ imagination. If one considers the three main economic blocs – the United States, China and Europe – their monetary policy record is unambiguous: they all engaged in easy credit and money printing to sustain growth and avoid bankruptcies and defaults. This time around, however, things may be different. Here are the scenarios we might face in the near future.

China: Chance to get stronger

China always resorted to lax monetary policy by offsetting the losses incurred by commercial banks lending money to unprofitable state-affiliated businesses. The ultimate goal was to prop up growth and make sure that slowdowns would be soft landings rather than crashes. Will Beijing act in similar fashion this time and do “what it takes” to soften the COVID-19 blow? The answer is, not necessarily.

The ruling party might instruct the central bank to inject enough money to keep the 2020 rate of growth at about 5 percent.

If Beijing is ready to acknowledge that a significant portion of the Chinese economy is fragile and that a major shake-up is in order to prune sluggish sectors – the construction industry, for example – the coronavirus could be a tempting excuse. The central government could thus help selected areas and companies (the supposed winners) and let many losers sink. If so, the 2020 growth rate could drop to about 3 percent. Social tensions associated with such a surgery could be mitigated, or even averted, under the shield of a propaganda campaign invoking national solidarity and patriotic cohesion in the face of a major threat. At the same time, government control over citizens’ lives would increase through measures introduced to fight the virus.

Put differently, the ruling party might indeed instruct the central bank to inject enough money to keep the 2020 rate of growth at about 5 percent. (Forget the official projections mentioning a 5.5-6 percent range.) However, it might also adopt a different strategy: pick its winners, stop the rise in inflation provoked by the widespread disruptions in supply chains and abandon many losers to their fate.

Will this hard-lending scenario materialize, hidden behind the veil of the coronavirus? We believe that two variables will matter. The first: the party cares about its support among the population and, more importantly, it needs to be on a solid footing with its own members. The pandemic could be handy as an excuse to silence dissent, but the final political outcome is far from certain. This could lead Beijing to decide against rocking the boat.

The second variable has to do with demography. China’s population, while aging overall, contains a large cohort of young, educated, ambitious and entrepreneurial people who are eager to make careers and money in the world of business. The more this group will be pushing from below for opportunities, the easier it will be for the political leaders to remove part of the safety net on which the old companies are thriving and make room for new, possibly more competitive firms. This would be good not only for China.

The U.S.: The elections, stupid!

At the beginning of March, the Federal Reserve Board (Fed) resisted President Donald Trump’s request for lowering interest rates to keep Wall Street happy and ensure sustained growth. Despite Mr. Trump’s earlier assurances that the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) would rise by 4 percent in 2020, qualified observers were far less buoyant. By December 2019, growth predictions were hardly reaching 2.5 percent.

The incumbent U.S. president needs a healthy-looking economy by the end of the year, when elections will take place.

However, the picture has become darker since then and the Fed seems to have changed its tack. After keeping a low profile for weeks, Chairman Jerome Powell responded to Dow Jones drops of about 30 percent in March with the announcement that the Fed would inject liquidity to the amount of $1.5 trillion “to address highly unusual disruptions.” More injections will follow.

Put differently, the incumbent U.S. president needs a healthy-looking economy by the end of the year, when elections will take place. He will probably continue putting pressure on the Fed, and the Fed will oblige. If the crunch gets worse and recovery is far away, Chairman Powell will have no desire to be cast as the main culprit for all sorts of economic misfortune. On the other hand, if the situation were to improve relatively quickly and Wall Street recovers a substantial portion of the recent losses, Mr. Powell will be the hero of the day, and Americans might remember it four years from now.

Summarizing the argument thus far, we shall soon see which way Chinese monetary policy will go, and we already know what the Fed is doing and where the U.S. policy is headed.

The eurozone: Lagarde’s moment

Frankfurt and Brussels are question marks. The public was expecting (and hoping) that the ECB would simply replicate Mario Draghi’s strategies. Easy credit and generous money printing were his default solutions to critical situations like weak banks, unsustainable public debt and sluggish growth. Indeed, COVID-19 may easily affect banks and public finance, and bring European growth into negative territory. Recent predictions put it at -5 percent.

ECB President Lagarde was absolutely right, even though she changed her mind a week later.

Economic activity in the old continent was already in trouble before the pandemic. Many companies may be unable to absorb the latest blow and go bankrupt. Their creditors (including the banking system) will suffer accordingly. Massive increases in public expenditure are certainly about to be launched, but investors will soon start wondering about public-debt sustainability in a number of countries. This issue, for a while dormant, will return as another source of concern.

Shortly before mid-March, new ECB President Christine Lagarde declared her board had unanimously agreed that central bankers should refrain from bailing out companies and governments, and that, therefore, no special money-printing program was planned. Even though Ms. Lagarde is exceptionally well acquainted with the Union’s political codes and jargon, the statement was surprisingly blunt. It prompted vehement demands for policy change, in the name of European solidarity. Yet the president was absolutely right, even though she changed her mind a week later.

The statute of the ECB is explicit. The bank can regulate the world of finance and do whatever it takes to preserve the purchasing power of the euro. It would be rather adventurous to claim that since refraining from another massive run of the printing presses could lead to a disintegration of the euro, such printing is the ECB’s duty. In fact, Mr. Draghi had set a dangerous precedent by de facto involving the ECB in fiscal policy. A bad precedent should not bind his successors.

Regrettably, Ms. Lagarde soon undercut her initial message by promising to inject new liquidity into the eurozone’s economy (which is equivalent to buying treasury bills). And, of course, the European Commission stepped in promising that member countries in need would get everything they asked for, regardless of what Frankfurt thinks of it. But it is unclear where the money will come from: new national indebtedness? Ms. Lagarde? Both?

Scenarios

We predict business as usual with regard to monetary policy in the U.S. (President Trump and Wall Street will be happy.) We may see even more money printing in China, possibly leading to currency tensions between Washington and Beijing (both currencies will necessarily weaken).

However, Beijing could also engage in relatively tight monetary policy as an instrument to improve efficiency in troubled industries. Finally, and regardless of Ms. Lagarde’s final opinion about the role of central banking, COVID-19 might persuade recalcitrant EU members to give more powers to Brussels in exchange for EU guarantees on their national debts. Fiscal harmonization is at hand.

In the meantime, one thing is certain. The Maastricht Treaty provisions are about to be taken from the shelf where they were put in 2008 and thrown in the dustbin.