How Covid-19 changed the Czech approach to public finance

During the pandemic, the Czech government ended decades of sound economic policy and began spending indiscriminately. The trend might prove hard to reverse.

In a nutshell

- Until recently, Czech public finances were managed in an exemplary fashion

- The pandemic derailed the country’s long tradition of fiscal responsibility

- The population now expects handouts from populist policymakers

Until just recently, the Czech Republic was the darling of the financial markets, at least in Central and Eastern Europe, a region that underwent a difficult and sometimes painful transformation from central planning to a market economy after the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989. Some postcommunist nations made a success of this process, others less so. The Czech Republic features fairly high among the former, alongside countries such as Estonia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia. The growth they enjoyed as a result of restoring the market economy, privatizing state-owned firms and liberalizing all trade and prices, bears comparison with the economic miracle seen in parts of East Asia in the second half of the 20th century.

The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund now classify these countries as advanced, not developing economies. The Czech Republic today ranks among the top 30 most advanced nations of the world in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita at purchasing power parity. The Czechs are now wealthier than the Portuguese, the Spanish and the Cypriots, on a par with the Italians and within range of the French. In 1989, this had been almost unimaginable. Such is the power of market economics, freedom and democracy, and of having the right economic incentives.

A different country

In the eyes of analysts, economists and financial markets, there was one respect in which the Czech Republic was unique. From 1989 onward it was characterized by fundamental macroeconomic stability. Before and after the split of Czechoslovakia in 1993, it was typically conservative, moderate and prudent from the financial, monetary and fiscal perspectives. Unlike the Hungarians and Poles, the Czechs did not experience a “wild” early 1990s with high inflation eroding the value of their savings. Nor did they inherit a heavy national debt burden from the communist era.

Czechs long had a deeply ingrained distaste for inflation. Even the communist government of former Czechoslovakia steered clear of high inflation and large public and private debt.

In that respect, Czechs were even more “German” than the Germans, who acquired strong anti-inflationary instincts before World War II due to their terrible experience with the hyperinflation of the Weimar Republic.

It is very telling that the Czechs are the only nation from the entire former Austro-Hungarian empire to still have a currency called the crown (“koruna” in Czech). Except for the Czech lands, no part of the old monarchy has used a currency of this name continuously since it was introduced by Emperor Franz Joseph I in 1892. Given the country’s long republican tradition, this may seem absurd, as “crown” is a typically monarchical currency name. In Europe, only monarchies (Denmark, Sweden and Norway) or their direct successors (Iceland) have crowns in circulation. But the Czechs have kept the currency name because no inflation or currency reform over those 130 years has been grave enough to cause them to ditch it.

Although Covid-19 was by now less serious, the government started new spending programs, none of which had anything to do with the pandemic anymore.

As a result, the Czech Republic was spared humiliating debt-club discussions, debt write-offs and international market pressure. After the Velvet Revolution, it even managed to avoid foreign currency mortgages and other loans, unlike Austria, Croatia, Hungary and Poland. The Czech National Bank has always tried to maintain low inflation, which in turn has meant low interest rates. As a result, there has never been a “nominal illusion” that foreign currency loans with lower rates are much cheaper. This illusion is always shattered by a subsequent weakening of the exchange rate, as happened in most of the above countries after the 2008 crisis.

I have always felt relief and satisfaction when visiting foreign investors, rating agencies and international institutions that say “the Czech Republic has no problems to address.” There is nothing a policymaker in a small open economy likes to hear more than “your country is economically uninteresting” and “has no major macroeconomic issues.” The best calling card is when journalists do not write about a country of our size, or when “dull and boring” is all, they can say about its economy.

That Czech households have long had a loan-to-deposit ratio below 100 percent (meaning that they have more in savings than in debt) – together with all the abovementioned factors – also explains why there is so little interest in adopting the euro in the Czech Republic. If your monetary policy is working, why change it? Why try to convince a nation of net creditors to take part in currency experiments when there is no reason for them to do so? The Czechs have long been the most euroskeptic of the EU members without a euro opt-out.

The financial crisis did not alter this mentality – quite the reverse. Even the sharp economic contraction of 2009, when GDP fell by almost 5 percent, did not dull the Czech instinct for good housekeeping. The fiscally responsible center-right government of Prime Minister Petr Necas and Finance Minister Miroslav Kalousek was brought down by a political scandal in 2013, but even so, managed to stabilize public finances with unpopular measures and put them back on a sustainable path after two recessions. The country even scored a record-high rating of AA- with both Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s.

The Czech Republic remained among the seven least indebted countries of the EU. After the period of prosperity between 2014 and 2020, and thanks to low interest rates and simultaneous growth in nominal GDP, it even brought its public debt down toward 30 percent of GDP in 2019. This was at a time when many eurozone countries were no longer able to keep their debt ratios sustainably below 60 percent of GDP – the level that eurozone members themselves had set as a safe upper limit.

Post-Covid reality

In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic turned Czech fiscal and monetary history on its head. In the Czech Republic, just like elsewhere, massive compensation schemes were introduced during the first wave of infections. And in the Czech Republic, just like elsewhere, the prevailing view was that the overriding need was to keep demand strong, as the demand crisis of 2008-2009 looked set to repeat itself.

By the end of 2020, though, it had become clear that the problem was of a rather different nature. Demand remained strong, but thanks only to huge public spending. A double amendment of the Budget Responsibility Act first softened and then entirely deactivated the fiscal rules for the structural deficit, which are meant to keep public finances manageable.

People were paid for work they did not do, firms for goods they did not make, and service providers for services they did not provide. Working from home became the rule rather than the exception. The economy was running at 75 percent, but everyone was getting paid as before. A systematic process of “lethargization” of the population began, primarily at the expense of the public. Public finances became a black hole in which anything could be hidden. It was as if an abstemious man had discovered a secret stash of alcohol, got a taste for it, and now could not walk away. Where in the past, parliament had wrangled over single billions of crowns, all of a sudden hundreds of billions did not matter.

As if that was not enough, the populist section of the political leadership, beguiled by how nicely things were working on debt, began to step on the accelerator. Although Covid-19 was by now less serious, or even immaterial, the government started to hand out gifts – one-off benefits and extra pension hikes, bonuses for civil servants, and more and more new spending programs, none of which had anything to do with the pandemic anymore. Society discovered another, darker side to its psyche – the free rider. Work less and get more became the motto. Politicians who could not offer this were unelectable. To cap it all, a massive personal income tax cut was passed at the end of 2020, adding to the fiscal stimulation of the economy. With supply, production and logistics at a standstill, this inevitably led in 2021 to an unprecedented combination of high inflation (currently around 17 percent) and dramatically high public budget deficits (-6 percent) due to rising expenditure and falling revenue.

The way back will not be easy, especially at a time of extraordinary costs caused by the war in Ukraine.

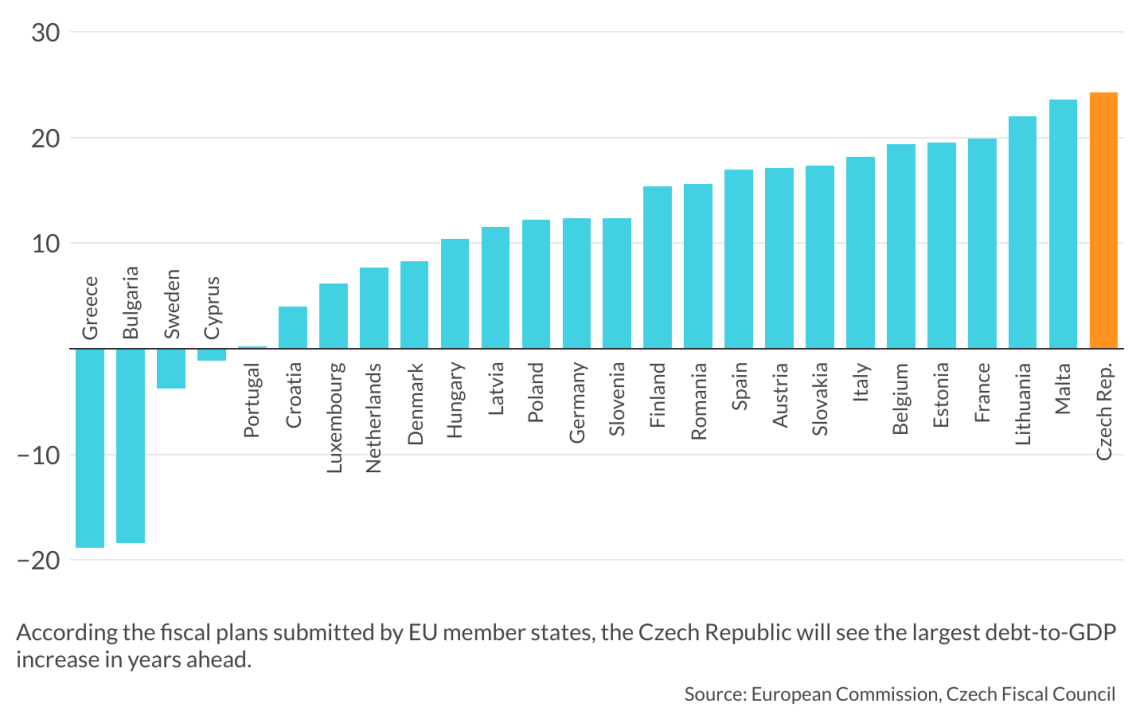

The southern countries of the eurozone suddenly began to look less like cautionary tales and more like close neighbors and friends. Greece had a deficit similar to the Czech Republic. A huge structural deficit – a systematic imbalance between expenditure and revenue of about 3 percent of GDP – formed. No one knows how to get rid of this, because easy-money populism has taken over the entire political scene and cannot be switched off. Almost unbelievable, the previously moderate and prudent Czech Republic is also now bottom of the class in terms of the 2019-2024 outlooks in the Convergence Programmes that all EU member states have to submit to the European Commission (see table). The ratio of public debt to GDP in the Czech Republic has meanwhile increased by a full 10 percentage points in just two years (2020–2021).

The way back will not be easy, especially at a time of extraordinary costs caused by the war in Ukraine. We will need to switch back to the other side of the Czech national brain, the side containing the financial conservatism of past decades. But it will hurt.

Scenarios

The first scenario is that the scary public finance outlook will induce the government to change tack on fiscal policy. In 2021, a moderate center-right coalition running on a platform of ending unbridled debt defeated the populist coalition that had been in power at the time of Covid-19. It even overhauled the 2022 budget. However, the attack on Ukraine and the related migration, energy and inflation crisis has dramatically complicated the opportunity to put public budgets on a sound footing in the near term. Everyone wants new spending, compensation and money. People also want the government to cut taxes, especially indirect ones. On top of that, even one of the ruling parties supported tax cuts at the time of Covid-19. However, it is possible that budgets will return to a sustainable path within three years. The probability of this scenario is 40 percent.

The second scenario is one of continued and growing populism leading to a gradual collapse of public finances in the medium term. New waves of cheap political promises can be expected as the number of senior citizens completely dependent on the state pension rises and the easy-to-manipulate free-rider phenomenon grows. The majority feel that they are unfairly contributing more than others to the public coffers. People are easily won over by the argument that it is possible to take even more and contribute even less with no visible consequences in the short term, especially with local and presidential elections looming. In such a case, public finance would continue to “fly on autopilot,” with no one knowing where the nearest mountains on the flight path are. The probability of this scenario is 60 percent.