A reborn Dominican Republic?

First ruled by various colonial powers, the Dominican Republic was subjected to a long dictatorship after independence. Now, the small nation appears to have successfully sown the seeds of progress, and the business environment is improving at a rapid pace.

In a nutshell

- Dominican history is fraught with crises

- The country seems to have overcome this legacy

- Socioeconomic indicators show progress

The slew of new nations that emerged after World War II spurred a major interest in how states are born. It was widely theorized that salient crises during and after birth were most likely to define peoples’ political memory and political culture.

Seymour Martin Lipset was a major contributor to this debate and used it to illustrate how exceptional the birth of the United States had been. Aside from the positive example of George Washington, it was also noteworthy that the Founding Fathers acted within a framework of established British political and legal institutions. They were all essentially Englishmen.

The many “births” of the Dominican Republic, in contrast, were marked by turmoil. The political culture developed mostly through crises, private and public. Whether under Spanish, Haitian or French rule, or any of the homegrown dictators in between, Dominican history is, in the words of Robert D. Crassweller, “a tale of struggle, the authoritative sorrow and disasters so prolonged that it has no parallel in the annals of the hemisphere.”

Occupation and authoritarianism

In its early days, not only did the nation not have a colonial framework to fall back on, it also lacked an exemplary democratic leader to guide it. Unlike its French neighbor, Spanish Hispaniola was a sparsely populated pastoral and free-grazing territory. Demographic differences between the two would determine much of the national history thereafter.

No sooner had Haiti become independent than it began a series of invasions of Spanish Hispaniola. In 1821 they came to stay. Despite the many attempts to “Haitianize” the population, Dominicans resisted – and that opposition first engendered a sentiment of national identity. Dominican historian Frank Moya Pons maintains that the expulsion of the Haitians in 1844 was because Dominicans considered themselves totally different from the invaders on the basis of “cultural traits such as language, race, religion and domestic habits.” Dominican identity and the country’s first “birth” (independence in 1844) was based on anti-Haitianism.

There is widespread agreement that the American occupation achieved three positive things.

Before the nation could establish itself on a stable foundation, influential actors – fearing another Haitian invasion – invited Spain to annex Spanish Hispaniola. It took a destructive war of restoration to evict the Spaniards and celebrate another “birth” in 1865.

Chaos followed – a war between regional caudillos leading to the rise and fall of 15 different governments followed by another foreign occupation, this time the U.S., from 1916 to1924. Paradoxically, despite the general dislike of and opposition to the Americans, there is widespread agreement that their occupation achieved three positive things: it organized the first precise and irrevocable system of adjudicating land titles; it eliminated the Dominican debt to a number of foreign nationals; and it tamed the political bandits (gavilleros) who perpetually destabilized commerce and agriculture. Unfortunately, there was another result: the creation of the Dominican police force that would become the main pillar of the brutal 30-year dictatorship of Rafael Leonidas Trujillo (1929-1961).

Modern state

With his assassination, there began another debate over how the nation should be reborn. Most scholars believe the Trujillo era left very little in the way of human resources adequate to the needs of a democratic order. In a rare and counterintuitive argument, however, Richard Lee Turits maintains that despite his monumental hubris, Trujillo tried to promote critical elements of the modern state – tourism, trade, foreign and domestic investments. He argues that there is much to the dictator’s claim that in the 30 years of his reign the country achieved financial independence, definite borders (with Haiti), a stronger sense of identity and an enlarged middle class. Fatefully, it was this class that brought about the demise of Trujillo and his era.

President Joaquin Balaguer, who governed between 1960-1962, 1966-1978 and 1986-1996, made a similar argument. He stated that the Trujillo years had “ended the stage of colonialism,” establishing the bases for national stability and national identity as well as an acceptance of foreign investments. During the period Mr. Moya Pons defines as “neo-Trujillismo,” Balaguer managed to avoid any revanchist outrages while moving forward. He erased the legion of Trujillo names, including that of the capital (Ciudad Trujillo became Santo Domingo again). He also nationalized the estimated $500 million of Trujillo holdings.

Facts & figures

Dynamic elite

Dominican author Esteban Rosario describes the upper class of Santiago as English-speaking, well-versed in the U.S.’s commercial culture and open to American and other foreign investments. His findings were confirmed by two Belgian economists who found that among those they termed the “dynamic elite,” 50.4 percent favored foreign investments, 21.7 percent favored state regulations and control, and only 15 percent rejected them.

In many ways, the personal profiles of these elites recently liberated from Trujillo’s all-encompassing monopolies, fits what Alex Inkeles calls “individual modernity,” a sense of personal professional efficiency, autonomy in dealing with authority, and openness to new experiences such as a productive collaboration between the public and private sectors.

A complex system of new parties and new coalitions has proven itself in 13 internationally supervised elections.

Good examples of that individual modernity are the country’s free trade zones which, as of 2018, numbered 74 with 673 firms employing 172,000 workers directly and about an equal number indirectly. Sixty percent of the firms are Dominican-owned. Dominican entrepreneurs also took advantage of the trend favoring nearshore manufacturing. This new entrepreneurial spirit has led Dominicans to make productive use of the country’s annual $5.5 billion in remittances, as well as of the opportunities offered by the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR). Domestic investments in the all-important tourism sector have also paid off handsomely.

The airport in the major tourist development in Punta Cana, built by the private sector, is now the busiest in the country. Important aspects of this culture of modernity are slowly seeping down to the general public. Illiteracy is declining and women are entering the workforce in greater numbers. Also demonstrating close public, private and international coordination is the successful vaccination program against Covid-19. The Dominican Republic is currently the third-most inoculated society (after Chile and Uruguay) in the hemisphere. Every worker in the tourist sector was vaccinated – a necessity as the sector undergoes a resurgence.

Finally, and crucially, a complex system of new parties and new coalitions has proven itself in 13 consecutive, internationally supervised elections. National elections are festive affairs as this author observed on two occasions.

Great strides

There is no naysaying the very real strides and successful policy choices of the “reborn” Dominican Republic’s leadership. It proves that entrepreneurship under a pluralist democracy is superior to development under tyranny. That Dominicans themselves are open about their reservations and criticisms of the pace of the change proves just how far the country’s democracy has come.

The present economy minister, university professor Miguel Ceara Hatton, argues that the country has made great strides in economic development but lags badly in terms of “quality of life,” access to clean water, decent public transportation, and adequate educational and public health standards. Additionally, he, like many others, is concerned with corruption.

Much of the ongoing success will depend on whether such an attitude becomes an integral part of the political culture.

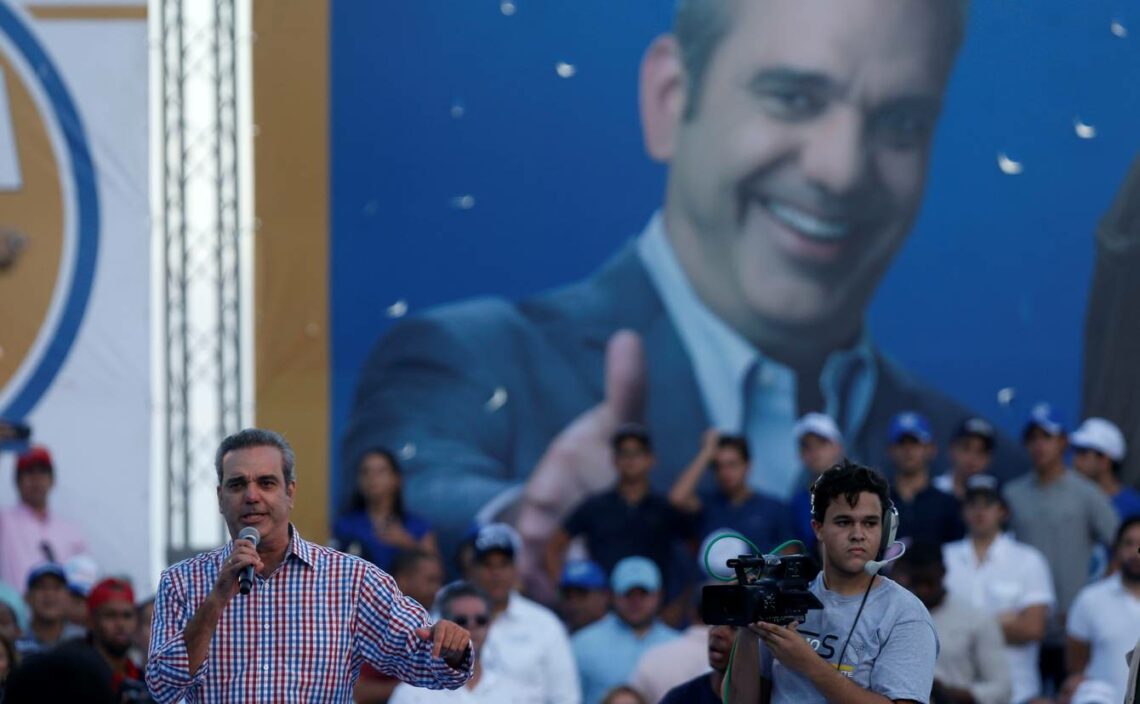

Transparency International ranks the Dominican Republic low in terms of corruption perception: 137 of 180 countries (along with Liberia and Paraguay). The Heritage Foundation concludes that “[c]orruption remains a serious systemic problem at all levels of the government judiciary and security forces, and in the private sector as well.” Evidence that much of the public agrees with this assessment was the 2020 election of Luis A. Abinader, who campaigned on an anti-corruption platform. Beyond being an issue of public morality, he argued that the problems of transparency and accountability were vital issues of national security and economic viability.

Much of the ongoing success of the “reborn” Dominican Republic will depend on whether such an attitude becomes an integral part of the modern political culture.