Hoping for a soft landing in the global economy

The war on inflation is unlikely to trigger a global recession, but one could still take place because of other problems in the international economy.

In a nutshell

- Low inflation is not enough to ensure a resumption of robust economic growth

- Excessive public debt, regulation and taxation are deterring private investment

- Policymakers have convinced entrepreneurs that inflation will drop further

In contrast with earlier predictions, most pundits now believe that the fight against inflation will not produce widespread recession. Current worries focus on the consequences of the Chinese slowdown rather than on the performance of the Western economies. Yet, growth in the West remains far from stellar. In the United States, gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to increase less than 2 percent in 2023 and less than 1 percent in 2024, while GDP growth in the 27-nation European Union is expected to be about 1 percent in 2023 and 1.5 percent the following year.

Most forecasters take a demand-driven approach. Aggregate demand (consumption plus investments) is strong and supply has followed, while higher interest rates have not wreaked havoc. Shocks like Russia’s war on Ukraine and supply-chain problems related to Covid-19 have failed to be the much-feared hard knocks.

Within this context, American GDP in coming years may be saddled by lower private consumption, which will suffer from debt servicing and lower government expenditure (tighter budgets). Meanwhile, the dynamic of EU growth will show the opposite signs for rather vague reasons, which include lower energy prices, expansionary programs promoted by Brussels and the anticipation that nominal interest rates have almost peaked and spared the most fragile member states. In fact, one suspects that most observers simply hope that in 2024, Germany will return to growth and lead Europe out of stagnation. In truth, this may be an exercise in wishful thinking.

This report argues that although the war against inflation is unlikely to trigger a global recession, one could still take place for other reasons.

More by Enrico Colombatto

Reassessing the dollar’s global status

Americans need a new debt ceiling again

Expect neither a recovery nor a recession

The relationship between growth and inflation

Let us first examine the relationship between growth and inflation. Growth is defined by the value of production, which in turn is propelled by the quantity and quality of fixed investments (equipment and machinery). There is no doubt that those who risk their capital in long-term production ventures like sound money. Inflation and interest rate manipulation are the opposite of sound money. Inflation is bad for growth, and all efforts to get rid of it are welcome, period. Yet, low inflation is still inflation.

Moreover, monetary conditions that emerge during a war against inflation are transient. Buyers’ purchasing power and preferences remain unstable, and producers are exceedingly vulnerable to mistakes, such as the wrong choice of products and production volumes. If producers believe that regulation and fiscal policies (taxes and subsidies) also become more volatile when inflation is high, then their entrepreneurial spirits will suffer even more.

The good news is that central bankers have succeeded in persuading entrepreneurs that inflation is under control and will drop below 3 percent before long. That does not mean that the entrepreneurs are correct, but it means that they are willing to take chances, replace their obsolete equipment and prudently expand production. This explains why the fight against inflation has not discouraged wealth creation and has avoided episodes of brutal recession.

As mentioned earlier, high interest rates and the end of loose monetary policy are unlikely to lead to recession. Yet, recession remains a possibility for at least three interconnected reasons: a public debt crisis, flagging private investment and excessive regulation and taxation.

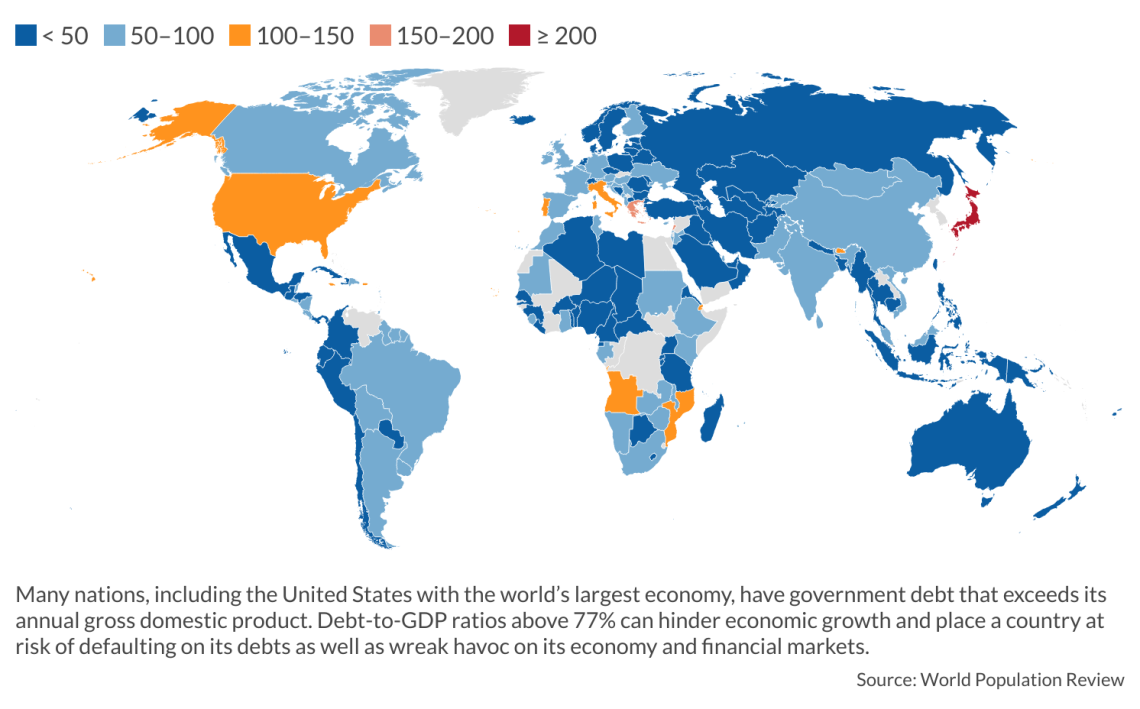

In the recent past, increasingly larger public expenditure has played a key role in ensuring that low growth or stagnation did not appear in official figures and qualify as a recession. As a result, the public finance situation has remained critical in several large Western economies and, in some cases, has deteriorated.

Facts & figures

Will nations cut public debt and spending?

Will politicians do what it takes and cut public expenditure when elections are around the corner, both in the U.S. and the EU? If they do not, three equally alarming possibilities open up.

The first possibility is that if taxation rises, household savings will suffer, and the resources available for private investments will dry up. Some observers will describe the consequences as an aggregate demand problem and perhaps ask for even heavier government intervention to stimulate the economy. In fact, production and productivity would drop (recession) and inflation would possibly follow.

Second, if public debt rises and authorities resort to printing money to finance it, inflation will accelerate. Policymakers’ credibility will be shattered, and uncertainty will cripple economic activities. That would not be a recession. It will be a meltdown.

Finally, if public debt rises and governments try to finance it through the market, interest rates will increase. Once again, households’ savings will finance public spending rather than entrepreneurial ideas.

The problem with regulation and corporatism

Regulation is on the rise. Recommendations to expand economic freedom have been pushed aside to benefit corporatism, a framework in which governments and powerful economic incumbents collude to prevent competition. Today, in some industries like banking, energy and agriculture, corporatism is already the norm.

Regulation is a heavy burden for all producers. Compliance is expensive, and uncertainty about future regulation adds to entrepreneurial risk. In other words, regulation is inefficient, but since some producers suffer more than others, regulators always find vociferous supporters – those who collude with the regulators – and meet disorganized and dispersed opponents.

Regulation tends to increase with inflation: those who lose from rising prices ask for government help and protection, while those who win strive to lock in their rents. Political pressure for administrative solutions builds up, government bureaucracy expands and bureaucrats churn out even more regulation to justify their role, regardless of the outcome.

The good news is that the successful fight against inflation tends to slow down the rise in bureaucratic expansion. Regrettably, however, the widespread belief in grand governmental designs (such as NextGenerationEU) plays a more significant role than inflation. It strengthens the corporatist drive and opens new horizons for regulatory expansion. Regulators could easily be the kiss of death for Western growth and fighting inflation will not stop their advance.

Scenarios

Avoiding a crash will require a reversal of trends

The fight against inflation benefits growth and certainly contributes to achieving a soft landing. Yet, it would be a mistake to believe that growth will resume once the war on high inflation is won. Growth results from the interaction of innovation, competition, profit-seeking, entrepreneurial spirits and, as mentioned earlier, the presence of enough private savings to finance private investments.

All these components do not appear on the Western leaders’ checklists. Nowadays, innovation is justified if promoted and approved by government agencies. Corporatism has replaced competition, profit-seeking is despised, households’ wealth is only tolerated if it can be used to finance public expenditure and entrepreneurial spirits are mobilized to obtain privileges and deterred from productive purposes.

Hence, future scenarios will be characterized by one clear issue and many ambiguities.

What’s clear is that if the trend is not reversed, limited productive investments will transform a soft landing into a soft crash. That applies to Europe and the U.S. and has nothing to do with the consequences of a tighter-than-desirable money supply, weak aggregate demand or energy prices. These prices will probably rise and affect production in various industries only because governments have persuaded fossil-fuel producers to stop investing and increasing supply.

The search for new scapegoats will soon intensify.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.