The escalating chip war between China and the West

U.S.-led efforts to throttle China’s chip industry will likely push Beijing to become more self-sufficient, as technology and national security become increasingly intertwined.

In a nutshell

- Western chip sanctions are unlikely to moderate China’s ambitions

- China cannot quickly replace its semiconductor supply from Taiwan

- Technology and national security will become more deeply intertwined

China seeks to position itself as the world’s leading science and technology superpower as part of its “comprehensive national security” strategy, introduced in 2014. Its course has been strengthened by the United States’ efforts to curb investments in selected Chinese tech companies and sensitive technology exports, and by its imposition of tighter trade restrictions to slow China’s rise.

Semiconductor microchips are at the center of Beijing’s economic security strategies, as they are needed for all present and emerging civilian and military technologies. They will help decide whether China achieves its geo-economic and geopolitical goals over the coming decades and replaces the U.S. as the dominant superpower and leader of the present global order.

China has already outpaced many technology forecasts from American intelligence and Western industry analyses. At this current pace – and given its position among the most important trade partners of the G7 countries – attempts to use traditional arms control methods and other multilateral regimes to contain critical dual-use technologies have become increasingly ineffective.

China is also an autocratic regime and a revisionist power with imperial ambitions and territorial claims not based on international law. It has blurred the lines between civilian and military uses of technology. Its “military-civil fusion” program forces Chinese companies to share all technologies and experiences with the People’s Liberation Army. Even many larger civilian infrastructure projects, both domestically and those of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), are designed for both civilian and potential military use.

Western sanctions and export controls have not only had negative impacts in China, but on Western companies as well.

Escalating U.S. restrictions

When U.S. President Joe Biden entered office in 2021, concerns were growing that emerging Western technologies had helped China become a serious military rival, one potentially ready to soon surpass the U.S. as the leading artificial intelligence superpower. After decades of promoting globalization and trade liberalization, the U.S. and the European Union are now making economic security a transatlantic priority. This shift followed China’s stealing of Western assets, technologies and patents under the cover of “joint” ventures and projects with foreign entities. In addition, over the last decade the West has increasingly seen supply chain disruptions in medical equipment, semiconductors and critical raw materials.

In August 2022, the Biden administration enacted the CHIPS Act to boost domestic semiconductor production and international competition, aiming to reduce its dependence on imports and exposure to supply disruption, as well as to protect the semiconductor manufacturing process from sabotage. Two months later, the White House announced a mix of sanctions and control instruments to defend U.S. intellectual property and national security and make it harder for Beijing to obtain or produce advanced chips. These include exports of equipment for producing chips at miniaturization levels at or below 14/16 nanometers. Industry experts believe that China has the technical know-how to produce advanced chips but still lacks the commercial ability to scale up production.

At present, the U.S. has a 10 percent global share in semiconductor production but dominates the value chain by 39 percent (rising to 53 percent together with Japan, Europe, South Korea and Taiwan). While the U.S. leads the upstream integrated circuit design process, the Netherlands and Japan have strong positions in midstream integrated circuit manufacturing as well as in packaging and testing.

Facts & figures

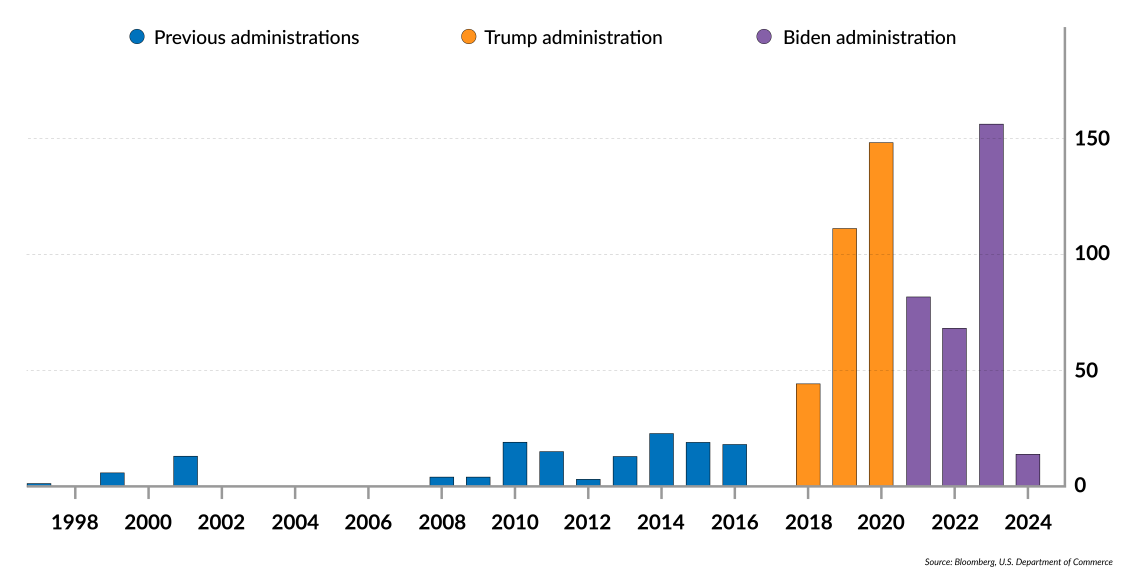

Chinese listings on U.S. Entity List, by administration

The Biden administration has laid out a “small yard, high fence” policy for exporting highly advanced technologies and semiconductor chips with military applications to China. As U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan put it in April 2023: “Our objective is not autarky – it’s resilience and security in our supply chains.” The government has also tightened the screening of foreign investments in critical sectors, like semiconductors. This follows the EU’s policies of “de-risking and diversifying” without “decoupling,” and tries to close loopholes in its sanctions over AI chip exports.

The U.S. has also strengthened its cooperation and sanctions coordination with Japan and the Netherlands, among others, to strengthen export controls on high-performance semiconductor manufacturing equipment. Companies of these two U.S. allies together produce a large share of the manufacturing equipment globally in the sector’s key supply chains. But neither U.S. nor Japanese export controls currently restrict the supply of older generation chips to China.

Meanwhile, the U.S. has proposed a “Chip 4 Alliance” with Japan, South Korea and Taiwan to make East Asia’s semiconductor supply chain more resilient. Taiwan produces 92 percent of the world’s most sophisticated chips at 3-5 nanometers and 80 percent at 7 nanometers and below. Its combination of technology leadership, supplier diversity and resilience in the global semiconductor industry is unique. It can hardly be copied elsewhere in the short or medium term.

Chinese countermeasures

Since 2015, Chinese President Xi Jinping has called for a national strategy to achieve self-reliance by reducing China’s dependence on Western imports of critical technologies and their components.

In contrast to the EU and the U.S., China is not just following a de-risking strategy, which seeks to reduce overdependencies and political-economic vulnerabilities. Instead, Beijing has adopted a decoupling policy from Western dependencies by seeking “technology autarky.” President Xi has also pushed companies to increase Western dependence on China, to weaken transatlantic ties and the West’s global influence.

The very notion of de-risking stands in direct conflict with China’s geo-economic and geopolitical ambitions: Beijing has perceived U.S. sanctions as a declaration of economic hostilities, given that semiconductors are China’s technological Achilles’ heel and most significant import item, even ahead of fossil fuels.

Beijing’s 2015 Made in China strategy had already defined a goal of increasing chip self-reliance from 10 percent to 70 percent by 2025 (though that has already proven unrealistic). Later, the target was adjusted to 75 percent by 2030. Beijing has invested some $150 billion in its semiconductor industry including research and development facilities since 2015 – more than any other economy. Not long ago it was thought that China’s Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC) would need seven years to catch up with today’s Western technology leaders. But SMIC and Huawei Technologies Co. have progressed quickly, using American technology to make advanced 7-nanometer chips in 2023.

In retaliation for U.S. sanctions, China has considered new restrictions on its rare earth exports. It controls 80 percent of the worldwide refining capacity for these minerals, which are essential for high-tech weaponry as well as batteries, screens and many other high-tech products. But any such export reductions might accelerate U.S. and EU reshoring, onshoring and friend-shoring manufacturing projects, as was the case with Japan in 2012.

Facts & figures

China-Japan rare earths dispute

- Year: 2010 (unofficially)

- Event: China restricted rare earth exports to Japan (falling short of a complete ban). This action coincided with a maritime dispute.

- Impact on Japan: Though China downplays the action, it spurred Japan to diversify its rare earth supply chain, leading to increased “near-shoring” – manufacturing in nearby countries – by 2012.

- Note: The exact details of the export restrictions remain debated.

China has banned the import of purchased products from U.S. memory chipmaker Micron for its critical infrastructure and other domestic sectors since May 2023 because of “serious security risks.” Micron was producing a quarter of the world’s DRAM memory chips, and China accounted for almost 11 percent of its sales in 2022. In 2023, it also imported a record amount of semiconductor equipment from the Netherlands, Singapore and Taiwan ahead of the implementation of new U.S. export restrictions. Last summer, China added another $41 billion to its China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment State Fund, launched in 2014 to boost its chip industry.

Last July, Beijing restricted its exports of two key metals, gallium and germanium, widely used in semiconductors and electric vehicles. While Chinese leaders seek to improve their bargaining power toward the U.S. in the short term, these policies also highlight its efforts to become the world’s most important supplier of many critical raw materials (CRM) and refined products. Beijing seeks to control the most important technology and value chains to support its strategy of asymmetric interdependence. China has already used its existing rare earth supply monopoly to extort Japan in 2010, when it stopped exports of rare earth elements over a territorial conflict.

Beijing has hit out at Western companies from all sectors and might further escalate tensions in the coming years. Its anti-espionage laws have been broadened since 2023 to cover the ill-defined “threats to national security.” In 2022, a Chinese government directive adopted a document referred to as “Delete A,” meaning “Delete America.” The program requires state-owned companies in finance, energy and other sectors to replace foreign software in their information technology systems. It includes over 60 of China’s 100 largest listed companies.

China also seeks to dominate the “legacy chip ecosystem” (those produced with older process nodes). This could enable China to turn off older chips in Western critical infrastructure and smart devices as well as open backdoors for state-supported espionage.

Scenarios

Less likely: The West retreats from sanctions

Western sanctions and export controls have not only had negative impacts in China, but on Western companies as well. As the Chinese market consumes 40 percent of the worldwide chip supply, any export ban of chips to China will inevitably have repercussions on the world economy.

The present Western chip restrictions are not likely to succeed in convincing China to moderate its geo-economic and geopolitical ambitions to become self-reliant in semiconductor chips. In the medium term, Chinese technology companies could become more independent by accelerating their own development in areas such as AI, allowing them to become much freer from Western control and influence. Hence, they could also become more dangerous in the long term.

To ward against this outcome, the U.S. and its allies could revoke their chip sanctions toward China in the hopes of moderating Beijing’s policies.

Moderately likely: Tensions lead to a full U.S.-China decoupling

In another scenario, the West will try to intensify sanctions to contain China economically, technologically and militarily. This could ultimately decouple the West from China, thereby ending the era of globalized trade.

Any reshoring projects for expanding U.S. and European semiconductor production capacities will demand massive upfront investments. Chip manufacturing costs are estimated to be 50 percent higher in the U.S. than in Taiwan due to higher labor and other cost factors.

It might only be a matter of time for China to catch up to the U.S., though it could face further U.S. embargoes until it does. SMIC was able to acquire spare parts and technical services to maintain its 7-nanometer production facility, despite the latest enhanced export controls and enforcements. Supporters of the U.S. restrictions hope that SMIC will run out of its stockpiles and material supplies before it can manufacture cutting-edge chips. But Huawei and SMIC are planning to produce the advanced, 5-nanometer ASCEND 920 chip – which would narrow the gap with the West’s cutting-edge 3-nanometer AI chips and with the prospect of 2-nanometer chips.

Most likely: Escalating chip race

For the time being, China cannot replace its semiconductor supply from Taiwan, as it would hurt its national economy and increase the cost of its geo-economic competition with the U.S. A military invasion of Taiwan and the subsequent semiconductor supply disruption would certainly also raise the costs for Beijing.

If the U.S., the EU, Japan and other Western countries want to avoid a complete decoupling, they will have to balance their economic security interests against overly protectionist and mercantilist policies, which can lead to inefficiencies, higher costs and stifled innovation.

At the same time, Beijing’s more aggressive policies of “economic coercion” for self-sufficiency and decoupling from the West are not likely to deter many other countries from joining U.S. sanctions and export control efforts. They will rather produce the opposite effect, by escalating the global battle for the world’s most advanced semiconductors and chips. In the future, technology and national security will become ever more deeply intertwined in a fragmented world.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.