Ethiopia-Somaliland deal risks regional tensions

Ethiopia and Somaliland stand to benefit from the agreement, which will likely reshape geopolitical allegiances across the Horn of Africa.

In a nutshell

- Ethiopia appears willing to recognize Somaliland in exchange for sea access

- The announcement has angered other East African states

- Resentment over this new alliance could reignite conflict in the region

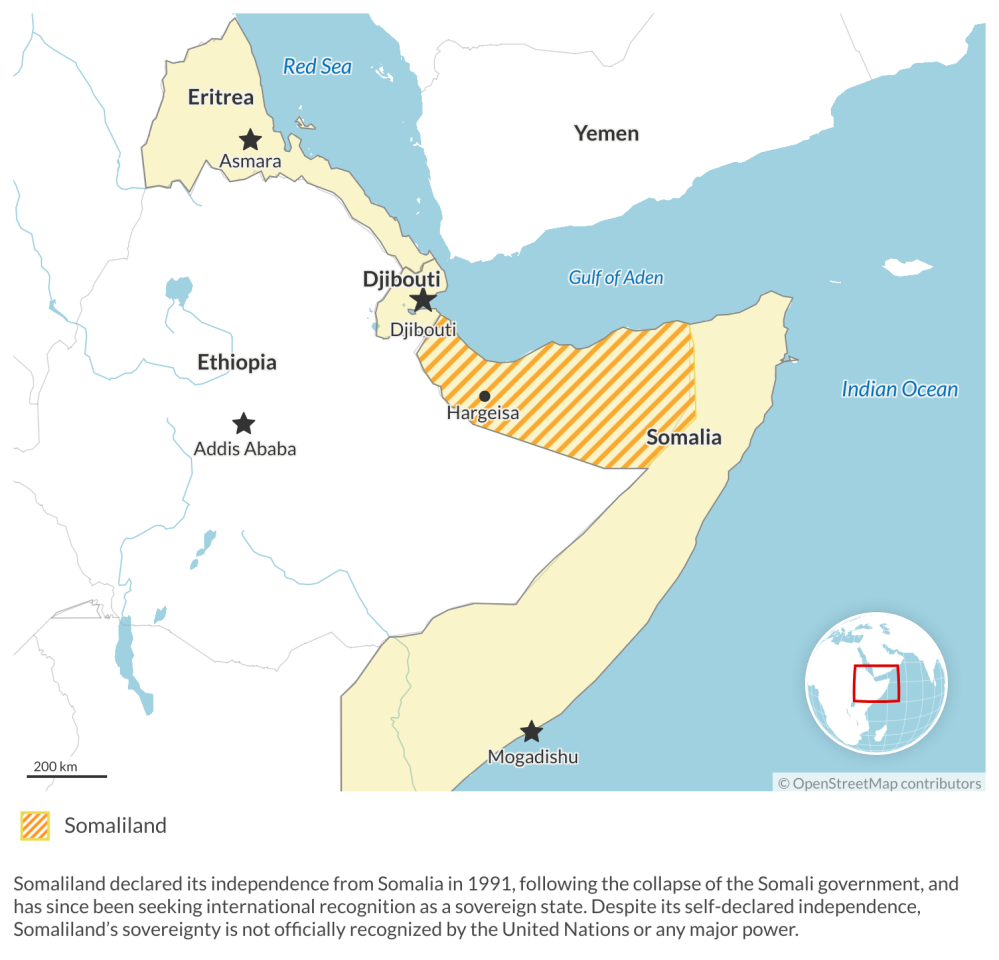

On January 1, 2024, Somaliland President Muse Bihi Abdi announced that an agreement had been reached with Ethiopian President Abiy Ahmed: Somaliland would grant landlocked Ethiopia access to the Gulf of Aden, and Ethiopia would recognize Somaliland as an independent state.

Two days later, Ethiopia issued a more measured statement referring to “an in-depth assessment toward taking a position regarding the efforts of Somaliland to gain recognition.”

The deal would likely benefit both parties. But, even if not fully implemented, it may reshape the balance of power and revive old conflicts in a notably volatile part of Africa.

‘Geographic prison’

For Ethiopia, a regional power with hegemonic ambitions in the Horn of Africa, access to the sea is vital. The country lost its coastline on the Red Sea after the secession of Eritrea in 1993.

Ever since, Ethiopian nationalists have claimed the country was unjustly stripped of its rightful territory. In October 2023, President Abiy Ahmed declared the Red Sea was Ethiopia’s “natural boundary” and claimed that its population cannot live in a “geographic prison.”

Direct access to the Red Sea would also have economic benefits. Over the past decades, Ethiopia relied on Djibouti for the transport of more than 95 percent of its imports and exports. The country, which hosts several foreign military bases, charged Ethiopia more than $1 billion per year in port fees.

Under the deal with Somaliland, Ethiopia would secure less expensive and more reliable access to the Red Sea through the Port of Berbera, leasing a 20-kilometer stretch of coastline for a period of 50 years. The leasing scheme would also allow Ethiopia to build a naval base and develop a commercial port on the strategic Gulf of Aden, an area which, unlike Djibouti, is not – at least not yet – a regional hub.

Facts & figures

Somaliland

Somaliland, unlike the Italian colony of Somalia, was a British protectorate until 1960. After gaining independence on June 26 of that year, Somaliland was an independent and sovereign state for just five days. On July 1, the country voluntarily merged with the Italian-administered Somali territory, giving birth to the Republic of Somalia.

But in 1991, after a brutal war between the Somaliland-based Somali National Movement and Somalia’s Siad Barre regime, Somaliland declared independence again. And, since then, it has tried – and to a large extent, succeeded – to meet the requirements of a de facto modern and sovereign state.

Without international recognition, the state-building process in Somaliland has been a bottom-up process. So far, it has successfully integrated traditional authorities and Western-style institutions. With a population of 5.7 million, Somaliland has its own constitution, passport, army and currency. It also has a government, a president, as well as regular direct elections – unlike Somalia.

However, there are limits to sovereignty without recognition by other actors of the international system. Without official statehood, Somaliland cannot receive the financing and aid it needs to develop economically.

The deal between Ethiopia and Somaliland has several cooperation clauses, including some that would bring investment to the Berbera port and along the Berbera-Hargeisa-Wajaale trade corridor. Somaliland would gain a stake in Ethiopian airlines and closer military cooperation with Ethiopia. All of these have the potential to boost the region’s economy. However, the real question is whether Ethiopia will officially recognize Somaliland’s independence. The matter has become more pressing and complex after the recent discovery of oil reserves off the Somaliland coast.

Shockwaves across the Horn of Africa

The deal was met with enthusiasm in Somaliland, but also triggered protests. The defense minister resigned, declaring that allowing Ethiopian troops into Somaliland posed a vital threat to national security.

Somalia declared the deal null and void and called it a direct attack on its sovereignty and territorial integrity. The agreement openly defies the “One-Somalia” policy and weakens Mogadishu’s stabilization efforts.

In 2006, Ethiopia significantly influenced the outcome of conflict in Somalia by defeating the Islamic Courts Union, a group that held control over parts of the country. Not surprisingly, terrorist group al-Shabaab claims that Ethiopia is an invader. The group has vocally denounced the deal and will likely exploit it to expose the weaknesses of the federal government. But the Somali government may find itself between a rock and a hard place. Defying Addis Ababa could have consequences for Somali security, considering Ethiopian troops constitute one of the largest contingents among peacekeeping groups in the country.

Facts & figures

Egypt, which has an ongoing dispute with Ethiopia over the Nile waters and fears competition in the Red Sea, sees the deal as an attempt by Addis Ababa to destabilize the region and assert its hegemony. Ethiopia’s ambitions have also reignited old tensions with neighboring Eritrea, which has sought rapprochement with Mogadishu.

The African Union, in turn, has also expressed concern and urged all parties to exercise “restraint and de-escalate.” After the recent wave of military coups, the organization fears the creation of yet another nexus of instability in the Horn of Africa, or the setting of a precedent for a secessionist movement. (Still, in 2005, an African Union fact-finding mission concluded that Somaliland’s claim was “historically unique” and “self-justified.”)

For the United States and the United Kingdom, which invested heavily in Somalia’s stabilization, the deal poses a challenge. For historical and geopolitical reasons, both countries have engaged with leaders in Somaliland, but always fell short of officially recognizing it as a country. Somali and Somaliland diasporas are also important actors in both countries, capable of putting pressure on political decision-makers.

Scenarios

The agreement has unleashed new tensions in a region torn apart by war and insurgency, where political instability remains a root cause of poverty and displacement. Two main scenarios should be considered.

More likely: Increased tensions

Under a first, more likely scenario, Ethiopia’s hegemonic ambitions and Somaliland’s push for recognition will increase geopolitical tensions and alter regional allegiances. Mogadishu and Cairo will grow closer, and Addis Ababa will clash with Eritrea again. Moreover, rivalries between Djibouti and Somaliland will likely intensify. The deal may also weaken the ongoing state-building process in Somalia.

There have been signs of friction already. Somalia has turned back an Ethiopian plane headed to Somaliland. Still, the most likely outcome would stop short of a regional conflict. While Somaliland would not achieve international recognition, it would also not be integrated into Somalia, remaining a hybrid entity.

Less likely: Regional conflict

Under a second, less likely, scenario, rising tensions would lead to a regional conflict involving several actors, likely resulting in further fragmentation. This could be triggered by Abiy Ahmed’s decision to revive Ethiopian nationalism by rallying Ethiopians against an external enemy.

Alternatively, Egypt could conclude that Ethiopia’s ambitions in the Red Sea (including a military base) are an existential threat to its national security. Like the Nile, the Red Sea is vital for Egypt, with revenues from the Suez Canal amounting to more than $9 billion in 2023.

Domestic conflicts could also spark a regional war: for example, an escalation of the armed clashes in the disputed city of Las Anod, located along the oil-rich Nugaal Valley between Somaliland and Puntland, or al-Shabaab attacks in Ethiopia.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.