Neither peace nor war in Ethiopia

Ethiopia’s war is ending, but peace is not yet within reach. Many of the issues that sparked the conflict remain unsolved, and while Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has the upper hand now, this may not last.

In a nutshell

- Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed is in a strong position

- He will need to consider the other side’s demands

- Otherwise, conflict could break out once again

What Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed first described as a “law and order” operation has turned into one of the most brutal conflicts of 2021.

The country’s model of ethnic federalism appears to be rapidly disintegrating. Localized clashes have given way to a near-total war in which everyone has chosen a side, splitting the country’s political elite, civil society, private sector and diaspora. On the battlefield, the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF), the Eritrea Defense Forces (EDF) and Amhara militias have formed an informal allegiance against the Tigray Defense Force (TDF) and the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA). Across the regions ravaged by conflict, local militias have emerged.

In May 2021, the parliament designated the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) a terrorist organization. Then in June, after regaining control of most of the Tigray region, Abiy Ahmed scored a resounding victory: he was reelected, and his Prosperity Party won 410 of the 436 seats in federal parliament. In November, however, after gaining control of the entirety of the Tigray region, the TPLF and its militias launched an offensive in the Amhara and Afar regions and began marching toward the federal capital, Addis Ababa.

Tigray forces retreated a few weeks later and announced the withdrawal of all forces from Amhara and Afar. The war that has killed tens of thousands and displaced more than 2 million people may be about to end, but bitter political tensions remain.

Political and military advantage

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s political advantage results from several factors.

The first is that, while he is often pictured as the instigator of the conflict on the international scene, many in Ethiopia see TPLF as the aggressor.

After the overthrow of the Mengistu regime in 1991, and through the leadership structures of the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRD), the TPLF assumed a key role in military, political and economic affairs. This hegemony was weakened by the death of Prime Minister Meles Zenawi in 2012, and effectively ended with the rise of Abiy Ahmed in 2018. While the EPRDF rule was characterized by economic growth, progress, and relative stability, it was also marked by repression and power imbalances that fueled resentment among the country’s two largest ethnolinguistic groups, the Amhara and the Oromo.

Ahmed’s vision of Ethiopia as a unitary and centralized state resonates with many Ethiopians.

After coming to power, Abiy Ahmed dismantled the TPLF elite by reducing the presence of Tigrayans in the military, removing them from senior positions in state companies (through accusations of corruption) and creating the Prosperity Party. While the means were questionable, most Ethiopians approved of such changes. But inevitably, the TPLF came to see these moves as a political crackdown, concluding that the federal government was an existential threat.

A second reason for Abiy Ahmed’s success is his appetite for change. He came to power when the country was on the verge of collapse amid economic challenges, ethnic tensions, and a wave of violent protests. His initial reforms – including the release of political prisoners, a peace agreement with Eritrea and plans to open the aviation and telecom sectors to foreign investors – generated a wave of optimism and support that went beyond Ethiopia and created high hopes for change in the country.

Last but not least, Abiy Ahmed’s vision of Ethiopia as a unitary and centralized state, anchored in a nationalism forged in a shared “glorious past,” resonates with many Ethiopians.

Popular support combined with strategic allegiances, in turn, translated into military advantages. While severely affected by the conflict, the ENDF’s support base remains larger than that of the TDF. Moreover, the TDF decision to attack Amhara and Afar – two regions involved in land disputes and ethnic tensions with the Tigray – fueled hostility against the TPLF and generated momentum for Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who called on every able-bodied citizen to join the war effort.

Facts & figures

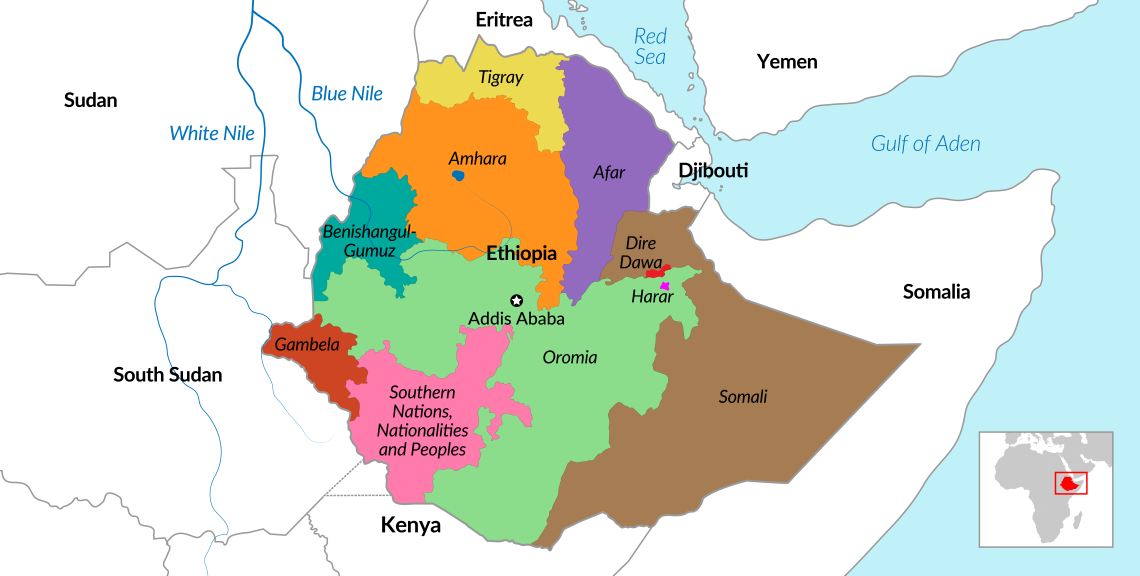

Ethiopia: A federal state, but for how long?

Regional and international shifts

Abrupt changes in Ethiopia’s internal situation have gone hand in hand with important shifts at the regional and international levels. The country is in a strategic location in the Horn of Africa and has been an important ally of the United States since the 1990s.

The first substantial change was the peace agreement with Eritrea, followed by an agreement on regional cooperation between Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia. Relations with Sudan, in turn, became more tense over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam and renewed border clashes in the disputed Al Fushqa region. Ethiopia has accused the Sudanese military, whose leadership is close to the TPLF, of taking advantage of the war to occupy disputed land.

On the international stage, the war has driven a wedge between the federal government and Western players. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed claims that Western interference in the conflict is a form of “humanitarian imperialism,” which violates the country’s sovereignty. The European Union’s threats to impose sanctions, as well as the U.S.’s decision to remove Ethiopia from the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), are seen by Addis Ababa as a manifestation of support for the TPLF.

Like in the Sahel, resentment against the West is increasing among some segments of the population. In May, a demonstration convened under the slogan “Our voice for freedom and sovereignty.” Protesters waved Russian flags and carried pictures of Xi Jinping.

Addis Ababa, perceiving the West to be hostile to its cause, turned east in search of diplomatic and material support. In early December 2021, when the war was at a critical moment, China’s foreign minister visited Ethiopia in a clear show of support to the government.

Russia, like China, represents the interests of the Ethiopian regime in the United Nations Security Council, and Moscow has recently signed a military cooperation agreement with Ethiopia. Iran, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates have also allegedly provided military materiel, including the drones that were decisive in disrupting the TDF supply route and stopping Tigray forces’ advance toward the capital.

No peace in sight

While the war may soon be over, the political forces behind it are still in place, threatening the perspective of sustainable peace.

The perceived political and military advantages of the federal government have allowed it to dictate terms, including “absolute respect” for the principle of territorial sovereignty. However, triumphs often turn into liabilities.

The fact that significant parts of the population, particularly among key constituencies like the Amhara, blame the TPLF for the conflict will put additional pressure on peace negotiations. In Tigray, resentment toward the federal government has only increased. Addis Ababa is now between a rock and a hard place. While refraining from attacking the TDF in Tigray is the only way to end the conflict, there is little room for meaningful negotiations. The TPLF is still labeled a terrorist organization. A state of emergency is still in place, granting the government the authority to detain people based on vague criteria. Overall, tensions persist as both sides stick to inflammatory rhetoric.

Regardless of the political outcome, Ethiopia will likely continue to strengthen ties with the East to the detriment of the West.

Moreover, the federal government will find it difficult to accommodate the demands of its allies. For Eritrea’s President Isaias Afwerki, the recent conflict presented an opportunity to neutralize the TPLF, a longtime enemy of the Eritrean regime. Asmara has no interest in ending the war, much less in a peace process that includes accountability for the atrocities committed during the conflict, with Eritrea risking further sanctions and condemnation.

On the other hand, Amhara regional forces, who are also accused of committing atrocities against Tigrayans, will likely resist any form of dialogue with the TPLF. Furthermore, there is no obvious resolution to the tensions created by the fact that Amhara officials have occupied portions of disputed land in western and southern Tigray. In such cases, the establishment of joint administrations could provide some stability in the short term, but it is not a long-term solution.

Scenarios

The most likely scenario is one of prolonged political negotiations, accompanied by sporadic clashes that may turn into a war of attrition.

On the political front, the government has announced the launch of the National Dialogue Commission. While this initiative may appease Western demands for peace, its impact will be limited. It does not, at least not for the moment, include the TPLF or the OLA.

An amnesty for those involved in the conflict could be declared. While this might dissuade armed leaders from engaging in further conflict, it would not be very popular. The federal government will ultimately have to address the claims of the TPLF and of the OLA, and the millions of Ethiopians they represent. While the Oromo played a vital role in Abiy Ahmed’s ascent to power, Oromo movements and, in particular, the Oromo youth have been targeted by the central government.

The most challenging issue remains the future of Ethiopia’s federalism. In the multinational state, ethnic and identity politics will continue to threaten stability and progress. Tensions between those who call for a strong and unitary state cemented around a common Ethiopian identity and those who defend a decentralized federation will persist.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed represents the first group, vowing to “make Ethiopia great again.” The last elections proved that he still enjoys considerable popular support. Leadership change remains unlikely in the short to medium term.

The formation of a transitional government and the holding of secession referendums (in accordance with article 39 of the constitution) seems unlikely. Negotiations will probably take place while the TPLF has the capacity and the motives to regroup, renew allegiances with other groups and prepare for war.

Regardless of the political outcome, Ethiopia will likely continue to strengthen ties with the East to the detriment of the West, reinforcing a trend that is already evident in the Sahel. The rising influence of countries like Iran, Turkey, and the UAE in the Horn of Africa – through Ethiopia – could affect the geopolitical balance in the Red Sea and reverse Israel’s diplomatic gains in the region.

Finally, while unlikely, the scenario of disintegration must be considered. If negotiations fail amid rising popular resentment, both sides may see renewed war as the best solution. Total war would have devastating humanitarian consequences in Ethiopia and beyond, leading to massive disruption in the Horn of Africa, a region characterized by chronic instability, violence, and displacement.