The EU’s imperfect choices on migration from Africa

Immigration will again fuel political tensions across the European Union, and governments will likely try to reduce the pull factors drawing African migrants.

In a nutshell

- The factors sending Africans to Europe will increase in the coming decades

- Expanded free trade could lift economic fortunes across Africa

- Migration will fuel political tensions, with the EU likely taking a harder line

As European Union foreign policy chief Josep Borrell stated in 2020, Europe’s political, economic and security interests are at stake in Africa, especially in migration. The economic impact of migration, for both origin and destination countries, generally tends to be positive. However, as Europe struggles with aging populations and African countries face the challenges of demographic growth, irregular migration flows – and how a growing share of the electorate perceives them – have fueled political tensions across the EU.

A win-win outcome will be difficult to attain. In the short and medium term, the EU will likely address irregular migration by readjusting (and in some cases reducing) the “pull” factors that incentivize migration, increasing border protection measures and establishing partnerships with third countries. But Europe could also play an important role in supporting export-based growth across the African continent, thus reducing migration’s “push” factors in the long run.

Demography and income

Nevertheless, migration push factors in Africa will remain and likely intensify over the next decades. The main reason is simple: economic growth and opportunities are not keeping pace with population growth. The rapid expansion of the global working-age population is shifting from Asia to Africa, and by 2050, more than half of the latter’s population will be under 25 years old.

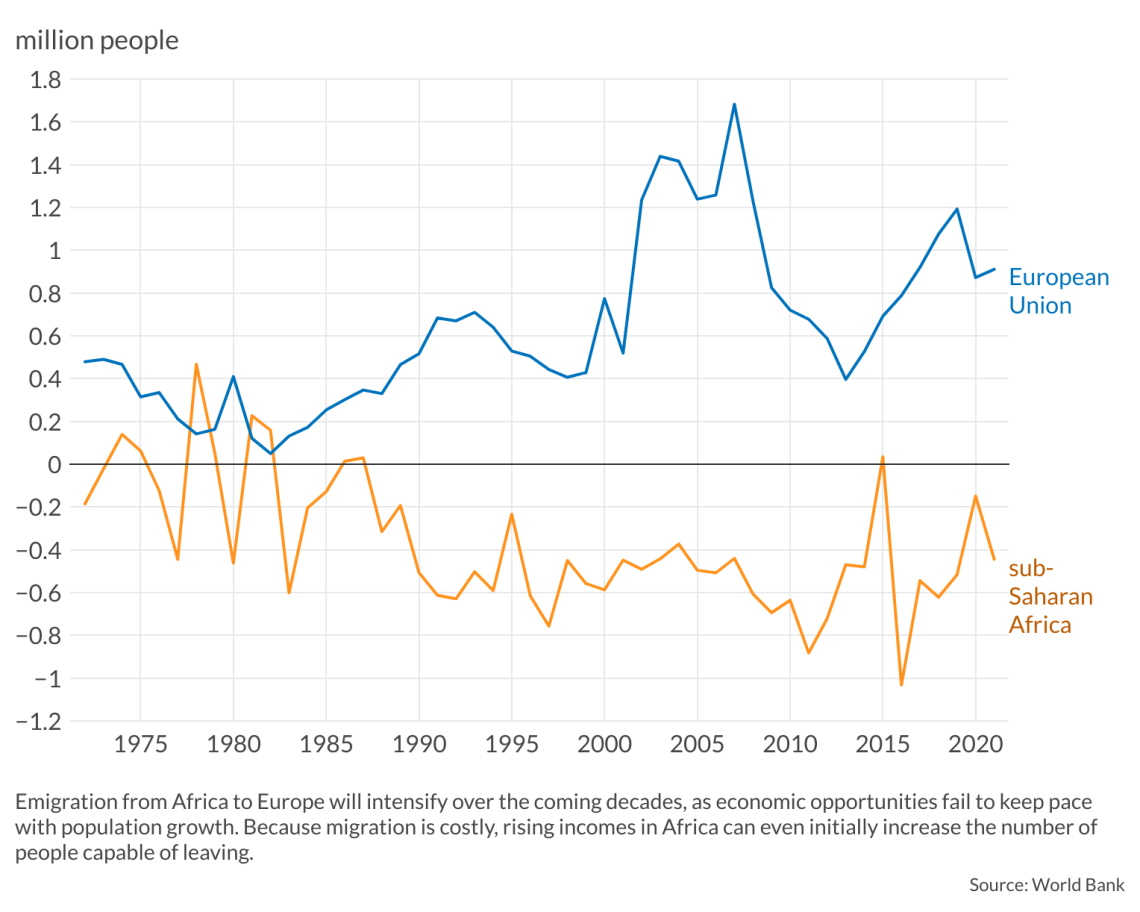

Income disparities between African and European countries will persist over the coming decades. Moreover, migration is costly and often not viable for the poorest. That means that under a scenario of economic growth across Africa, migration to Europe would increase during the initial stage due to enduring income disparities between the two regions.

There are many reasons for these disparities, and while Africa is a highly diverse continent, two factors stand out. First, late colonialism deeply affected African nation-building and state-formation processes and, consequently, governance patterns. In South Africa, for example, a national “state of disaster” was recently declared over persisting power shortages caused by poor governance and rampant corruption. In Sahelian countries, state fragility is one of the root causes of chronic violence.

The EU may be pressed to curb its protectionist instincts, reducing the regulatory hurdles that block African products from the European market.

A second factor is that African economies, unlike their Asian counterparts, could not benefit from the post-Cold War period of hyper-globalization that helped lift millions out of poverty. Without economic transformation – through industrial and agricultural revolutions, for example – the problems of low productivity and unemployment will likely remain. By 2047, according to the Institute for Security Studies, Africa is expected to account for a quarter of the world’s population – but less than 6 percent of the global economy.

The paths toward accelerated growth and development vary by country. In some cases, as in Rwanda, it was possible to move directly to a service- and knowledge-based economy. However, this kind of leapfrogging demands adequate digital infrastructure and technical innovation, while the services sector has less potential to increase productivity and create jobs. For countries with a vast territory and a large and growing workforce, like Nigeria, this may not be a solution.

Trade partners

At the same time, an increase in intra-regional and inter-regional trade has the potential to accelerate export-led growth and expand economic opportunities across Africa, especially after the enactment of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). While many of the reasons behind Africa’s poor trade performance can only be addressed by African countries, Europe could play a prominent role as the largest market for African exports during a period characterized by regionalization rather than globalization.

For decades, the approach to Africa’s economic challenges from Europe – both that of the EU and that of individual member states – has focused more on aid than trade. Aid, however, does not itself deliver (and may hinder) economic transformation processes. A growing consensus, already expressed in the Africa-EU Strategy, is that trade may be a decisive factor.

Read a related report by Teresa Nogueira Pinto

The UK-Rwanda deal: Risky attempt to curb illegal immigration

Another reality is that Africa and the EU are not equal trade partners. One obstacle is political in nature. Despite the idea of a “partnership of equals,” the EU continues to impose a political agenda going well beyond trade issues, using grand strategies like the European Green Deal. These efforts may do more harm than good even if driven by good intentions. In the long term, free trade could have a more significant and sustainable impact on African governance than external impositions while respecting African countries’ sovereignty and agency.

Moreover, the EU may be pressed to curb its protectionist instincts and reduce the regulatory hurdles that block African products from the European market. Agricultural subsidies notably distort trade. The EU’s rules-of-origin regime also remains complex and excessively demanding. European efforts to promote commerce with and within Africa must be grounded on reality; bans on agrochemicals, for example, are a double-edged sword, as they may compromise agricultural productivity in countries vulnerable to food insecurity. Likewise, the EU’s push for organic farming in Africa must not ignore that only 0.2 percent of the continent’s farmland is certified for this type of production.

Cautionary tale

Europe’s concerns with African economies are intimately connected with migration, which now drives its approach to the African continent. That is particularly visible in the Sahel, which became a top priority in the EU foreign agenda after the disintegration of Libya.

The EU approach has been determined by fears of large-scale irregular migration, which intensified after the 2014-15 migration crisis. To be sure, Sahelian countries are not the leading countries of origin of African migrants trying to get to Europe; the primary countries are Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria, followed by sub-Saharan African states like Senegal, Ivory Coast, Nigeria, Guinea and the Gambia.

Migration remains out of reach for most living in the very poor Sahel region. However, state fragility, terrorism, organized crime, communal violence and food insecurity have substantially increased in the number of internally displaced people and refugees within the region.

The Sahel region provides a cautionary tale about excessive interference, the limited impact of aid and the collateral effects of far-reaching agendas designed and imposed by external actors. Despite initial successes, the efforts to stabilize the region since 2012 – led by France, the EU and the United Nations – have largely failed. These failures, combined with perceptions of illegitimate foreign interference, led to rising anti-France and anti-Western feelings and violent anti-UN protests. These sentiments were then successfully exploited by other foreign actors willing to operate in the region, like Russia’s Wagner Group. Not surprisingly, this has provoked anxiety among European decision makers.

Electoral backlash

Regarding the pull factors, the EU focuses on creating conditions for legal migration, as evidenced by the 9.9 billion-euro budget allocated to the Asylum, Migration, and Integration Fund (2021-27).

However, political decision makers acknowledge that migration is no longer a marginal issue in European politics, with opposition to illegal migration reflected in electoral results across the continent. That has provoked changes in several countries. In Italy and Austria, governments have been elected on the promise of containing illegal immigration. In Sweden, Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson of the Moderate Party has described immigration as “unsustainable” and announced a “paradigm shift” to affect family reunification and rules for gaining citizenship. The government has also launched an informational campaign targeting potential asylum seekers.

Facts & figures

In several countries, concerns about rising irregular migration and how the public perceives it may fuel nationalism and radicalization. After the announcement of a controversial asylum partnership between the United Kingdom and Rwanda, the German government appointed a Special Commissioner for Migration in charge of addressing asylum requests (which numbered 244,000 in 2022), increasing regular migration and “significantly” reducing irregular migration. Policy responses discussed include quotas for legal immigrants and the return of people rescued from the Mediterranean Sea to countries in North Africa, where their asylum procedures would be processed in exchange for benefits such as advantages in visa applications or better trade relations.

Scenarios

A mutually satisfactory outcome between Africa and the EU is unlikely, at least in the short and medium term. In several African economies, remittances have become the largest source of external financing, outpacing aid and investment flows. Many regimes see emigration as a release valve amid high youth unemployment and political discontent. And while migration tends to benefit both origin and destination countries, illegal flows are increasingly perceived as a political risk across the EU.

Migration is driven mainly by economics, and, in the short to medium term, higher food and energy prices across Africa will remain important push factors. Refugee flows into the EU are expected to increase following the devastating earthquakes in Syria and Turkey.

Paradigm shift

Under this most likely scenario, collective efforts to manage asylum applications, reduce irregular flows and secure European borders will intensify, through partnerships with third countries, strengthening the Frontex border agency and its deployments abroad. EU member states will increasingly introduce policies to reduce illegal immigration while adapting migrant flows to specific economic needs. More countries will follow the UK’s lead in attempting to externalize the management of asylum requirements and irregular flows.

Increasingly, refugees, asylum seekers and economic migrants will be treated differently. Several states will likely adopt legislation to make sure that the profile of economic migrants matches the needs of the host country. In France, for example, immigration law will provide for the creation of residence permits for “professions under strain.” Germany is simplifying immigration rules for skilled workers and introducing a points-based system that mandates knowledge of the German language.

This scenario has two main risks. For one, schemes to attract migrants into specific sectors will be ineffective without more flexible labor markets. And – as seen after the disintegration of Libya – externalizing migration controls creates vulnerabilities for European security and weakens European soft power by creating the appearance of a double standard.

Disincentivizing migration

Under a second scenario, individual EU countries would adopt measures to contain illegal migration and reduce migration overall. While unlikely, this could be triggered by disruptions – such as a significant increase in anti-migration protests amid rising economic discontent and political polarization. Some countries may follow the example of Denmark, where the governing coalition (including Social Democrats, Liberals and Moderates) has described some areas of the country as “parallel societies.” The government is introducing restrictions on migration and a “zero refugee” policy, defining the Syrian capital of Damascus as a “safe zone” where migrants can return.

Under this scenario, EU relations with African countries would be strained. African economies would suffer, as Europe is the primary source of migrant remittances into the continent.

Incentivizing migration

Under a third scenario, EU countries would act in accordance with the approach proposed by the UN Global Compact for Migration. Refugee status would be expanded to include climate refugees. At the moment, such an approach is mostly the exception. In Portugal, where the number of both regular and irregular migrants has been increasing, more open immigration policies have recently been implemented to mitigate the effects of aging demographics.

Considering the current political context throughout Europe and the growing perception that border control is fundamental to sovereignty, this is the least likely course forward. It could lead to further social and political tensions, with many Europeans believing that their nations have reached the capacity to receive and integrate migrants.