The EU strives to avoid another Afghanistan

For jihadist movements celebrating the infidel’s humiliation in Afghanistan, it proves that patience ultimately pays off. For the Western actors engaged in anti-terrorism efforts, the quick fall of Kabul has demonstrated that containment is different from eradication.

In a nutshell

The announced but unexpectedly chaotic withdrawal of Western forces from the “forever war” in Afghanistan raised concerns among those African countries that have relied on international troops to contain the advance of terrorist groups. While recent events are already changing fragile security and political contexts across Africa, they could also have long-term and more diffuse consequences.

Lessons learned

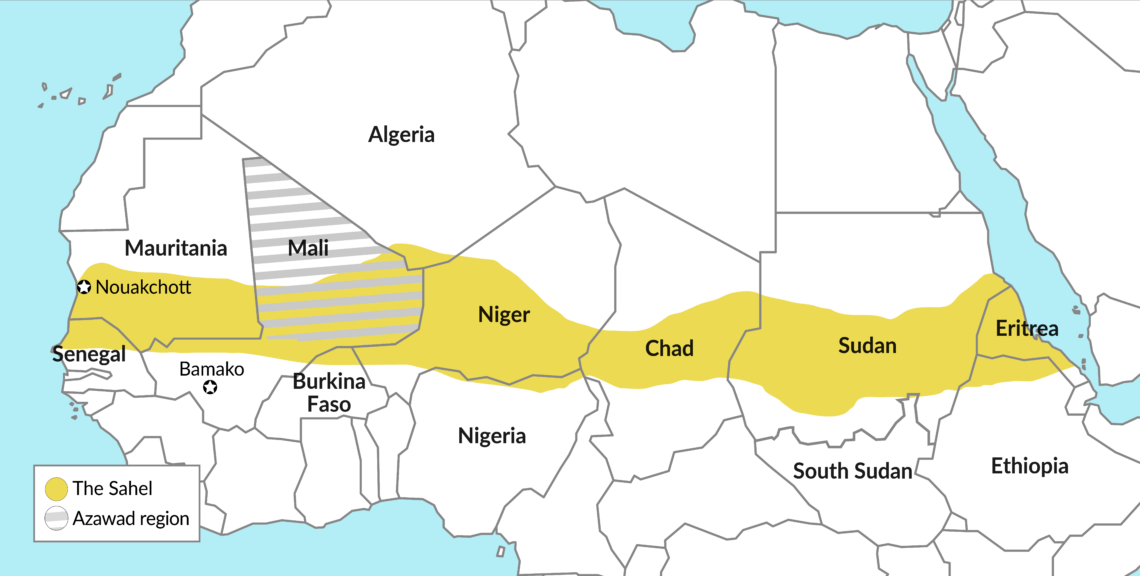

For the past decade, the European Union, particularly France, has assumed a preponderant role in anti-terrorism operations in the Sahel – the region in Africa that forms the border between the Sahara Desert and the savanna. This involvement includes financing mechanisms, training missions and troop deployment. The news, however, is far from encouraging. As terrorist groups expanded their reach within the region, the year 2020 became the deadliest since the conflict began, according to data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), NATO and the African Union (AU).

Of particular concern is the tri-border Azawad region between Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, where there has been an increase in the number and intensity of attacks perpetrated by two terror groups: Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) and the al-Qaeda-affiliated Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin, or JNIM).

The fall of Afghanistan has provided a psychological boost to Islamic extremists all around the world.

For the actors engaged in anti-terrorism efforts, the first lesson from the quick fall of Kabul is that containment is different from eradication. Within the zero-sum logic that often characterizes anti-terrorism efforts, a political or strategic retreat inevitably leads to advances on the opposite side. In contrast, for jihadist movements worldwide celebrating what they consider a humiliation of the infidels, the lesson is that patience ultimately pays off.

In August, in his first public message since 2019, Iyad Ag Ghaly, the Tuareg emir of JNIM, paid tribute to the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan and congratulated the Taliban for “two decades of patience.” For JNIM, the announced termination of Operation Barkhane, the French-led anti-insurgent effort, also amounted to a military triumph.

Many jihadist groups operating in the Sahel had previously pledged allegiance to al-Qaeda or Islamic State (ISIS). As the chief of British intelligence organization MI5 has pointed out, the fall of Afghanistan has provided a psychological boost to Islamic extremists worldwide. However, unlike the Taliban, these groups have no experience whatsoever in ruling and lack access to significant resources, networks of regional support or the military equipment and training required to secure the monopoly of the use of force.

Furthermore, the political context in the Sahel – characterized by extreme unpredictability and multiple divides over various issues – is different from Afghanistan. Jihadist leaders who fought the Soviets in Afghanistan and returned to Africa (namely Somalia, Egypt, Algeria and Libya) to expand the jihad have been an invaluable source of inspiration and played critical roles in consolidating terrorist groups. Today, these allegiances are more volatile and diffuse.

In the case of Somalia, however, the parallels with the situation in Afghanistan are clearer. Al-Shabaab was once the youth militia of the Islamic Courts Union which – despite its brutal principles – brought stability to the country in the early 2000s. At the same time, regardless of massive investment, military engagement and diplomatic efforts, state-building attempts in Somalia have consistently failed amid fragmentation, insecurity and corruption.

Diffuse effects

The Taliban government cannot afford to openly defy regional and international powers. The country is not likely to become a haven for jihadist movements in the short to medium term. However, given that more than half of the new government members face international sanctions, financial support to Afghanistan will be constrained. In this context, it is unlikely that the Taliban will maintain their commitment to banning opium production.

There are multiple intersections between illicit trade and terrorist groups operating in East and West Africa.

Besides minerals and private donations, heroin has been a critical source of funding for the Taliban. Poppy cultivation occupied 224,000 hectares in 2020 (a 37 percent increase compared to the previous year) and represented half of the country’s agricultural output. Afghanistan now accounts for over 80 percent of the global supply of opium and heroin. Some experts believe that the Taliban may try to diversify by further scaling up the production of methamphetamine, made through processing the wild ephedra plant widely available in the country. If heroin and methamphetamines remain the primary source of funding for the Taliban, the effects will be felt in Africa.

Since 2015, trafficking routes into the West have moved from the Balkans to East and Southern Africa. Zanzibar and Mombasa are now vital transit points for traffickers. In Kenya, the consumption of hard drugs among the youth has significantly increased.

A rise in the volume of drug trafficking and illicit financial flows would have powerful negative consequences for development and stabilization in a continent of porous borders, chronic unemployment and lack of opportunities for the young. There are multiple intersections between illicit trade and terrorist groups operating in East and West Africa, in the Horn and the Sahel.

Regional and international dilemmas

The Afghan debacle comes when important state actors are reducing their anti-terrorism efforts across the so-called “arc of instability” that stretches from the Sahel to the Horn of Africa.

Facts & figures

Following the sudden death of President Idris Deby on April 20, 2021, and faced with mounting internal security risks, Chad withdrew half of its G5 Sahel contingent deployed in the critical tri-border area. (The force comprises units from Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger.) Less than two months later, on June 11, French President Emmanuel Macron declared that Operation Barkhane, launched in 2014, would end “in an orderly fashion” by early 2022. The 5,100 French troops in the Sahel would gradually be redeployed.

Now, Paris is focusing on consolidating a new international coalition responsible for counterterrorism operations in the region. The new alliance is to emerge from the France-led EU Task Force Takuba created in 2020 to assist the Malian government. Based in Niamey, Takuba comprises units from several European countries. It has had an initial mandate for three years and is now supporting the G5 Sahel initiative.

In the last days of the administration of Donald Trump (2017-2021), the U.S. withdrew from Somalia, a country that may become an epicenter for global jihad. President Joe Biden has acknowledged that the terrorist threat “has metastasized well beyond Afghanistan.” The U.S. is now committed to “surgical” and remote approaches, as seen in recent drone strikes against al-Shabaab targets in Somalia.

Under this most likely scenario, the Afghan debacle will bring the return of realpolitik.

For China, which has vast interests across the continent and has to a great extent been a free rider of international and regional counterterrorism efforts, this is not necessarily good news. Beijing, however, is unlikely to replace the void left by other actors.

One global player, however, seems willing to increase its military footprint in Africa. Russia has been signing military agreements and deploying forces across the continent, including in Mali, where a Russian private military contractor may become responsible for the security of the military junta that has held power since the May coup.

Scenarios

Africa and the Sahel will feel the impact of the Taliban’s rise to power in multiple short-, medium- and long-term ways. The outcomes will be determined not only by the events in Afghanistan itself but, mainly, by the decisions of key actors – including jihadist leaders, African governments, and international players. From this background, two scenarios emerge.

Under this most likely scenario, the Afghan debacle will bring the return of realpolitik. Like in Iraq, events in Afghanistan have demonstrated that foreign-led state-building is an inglorious endeavor unlikely to succeed. The foreign-led projects, shielded by the military and seen by locals as an occupying force, carry exorbitant financial, political and human costs that make them unsustainable in the long run.

The above does not imply that international actors are also going to retreat from the Sahel. This is the case not least because these actors, and especially the EU, are aware of the costs of a scenario in which the region disintegrates further, and terrorist attacks escalate. However, political decisions will be pragmatic, based on the principle that politics is often about the art of the possible. Internal politics will also play its part: already on the campaign trail, President Macron will continue to pressure the EU to assume more responsibility for containing terrorism and preventing crises prevention in the Sahel.

The EU can be expected to do so through a more military-based approach, as evidenced by the Takuba force. While maintaining a low profile politically, Brussels will continue to complement this military intervention with financial assistance to the region’s countries. The leading foreign donor in the Sahel, the EU has provided more than 3.4 billion euros for various development programs since 2014. Now, the deployment of a Pan-European force in a volatile operations theater puts EU military autonomy to an important test. A strong EU presence on the ground is also critical to containing Russia’s ambitions in the region. For its part, benefiting from growing anti-French (and “anti-imperialistic”) sentiment, Moscow will likely seek to build its image as an agent of the region’s stabilization.

For political leaders in the Sahel and beyond, the return of pragmatism may pave the way for dialogue and negotiations with insurgents and even jihadist movements whose hopes for political recognition are enhanced after the victory of the Taliban.

Under this scenario, the terrorist threat would be contained but not eradicated. Such containment is a necessary, though not sufficient, condition for the next step: spurring state-building processes locally and political stabilization in the Sahel.

The establishment of legitimate and efficient governments and disciplined, effective security forces are conditions for stabilization. However, considering the security challenges, political divides and the widespread poverty that characterize the Sahel, these conditions are unlikely to be met in the short to medium term. While ongoing instability is very likely, it may remain contained to specific locations or spread throughout the region, with further human and political costs.

While less likely, the scenario of widespread chaos – unleashed, for example, by disintegration in Mali or Chad and the expansion of terrorist groups into Benin and Ivory Coast – remains probable. Such a development would lead to the further deterioration of the security outlook. Its characteristics would be the strengthening of transnational terrorist networks, expansion of organized crime and trafficking routes, massive displacement and the further increase of refugee flows trying to escape deadly violence.