The EU’s new China strategy is stress-tested

When the EU sent warnings to China over its human rights violations, it did not anticipate Beijing to respond with sanctions of its own. The new EU-China strategy of combining cooperation with assertiveness in its relations with the eastern giant may have its limits.

In a nutshell

- In March 2021, the EU imposed its first sanctions against China since 1989

- Beijing responded with countersanctions, putting the EU investment pact at risk

- Germany and France are scrambling to ease the tension

On March 22, 2021, the European Union, acting in concert with the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada, announced sanctions against the People’s Republic of China over the mistreatment of Uighurs in Xinjiang. The EU was sanctioning China for the first time since the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989.

The decision to join in on the measures resulted from Brussel’s new, multifaceted EU-China strategy. Beginning in 2019, the EU gradually replaced its disorientation about China’s global role with policies that treat Beijing as an important partner, but also a systemic rival.

Now, Europe’s approach to China is meant to be competitive when it should be, cooperative when it can be, and hostile when it must be. The United States is pursuing a similar strategy under the administration of President Joe Biden. However, there are significant differences in how the EU and the U.S. define and implement the approach.

Washington has adopted a dynamic stance: the more Beijing contravenes basic universal values in its policies, including human rights, the more vigorously the U.S. will seek to block the activities that could help China become militarily and technologically powerful. The EU-China strategy, on the other hand, does not feature such a direct linkage.

The EU’s shock

The EU China strategy underwent a decisive change when in March the decision to apply sanctions was made. This was based on two factors. Firstly, the Europeans wanted to close ranks with the Biden administration to help it restore the global democratic alliance that functioned before the presidency of Donald Trump (2017-2021).

Secondly, the calibrated measure was not supposed to upset the applecart or interfere with other parts of the bilateral relations agenda, such as the ratification of the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI). The EU only sanctioned four officials and one security agency in China’s Xinjiang province, tellingly omitting, for example, the top communist party official directly responsible for repressions in the region. Overall, the EU meant to signal to Beijing that it should get used to the idea that human rights matter, but hardly anything more than that.

The Chinese side responded forcefully, as if to say, ‘If you punch me once, I’ll punch you back three times’.

In the past, EU member states rarely spoke with one voice on issues concerning China, especially after the Union’s eastward expansion in 2004. However, the decision to join in the sanctions was unanimous, at least officially. Even so, Hungary’s foreign minister criticized the EU afterward, and Chinese officials were doubtlessly pleased to see this kind of internal discord.

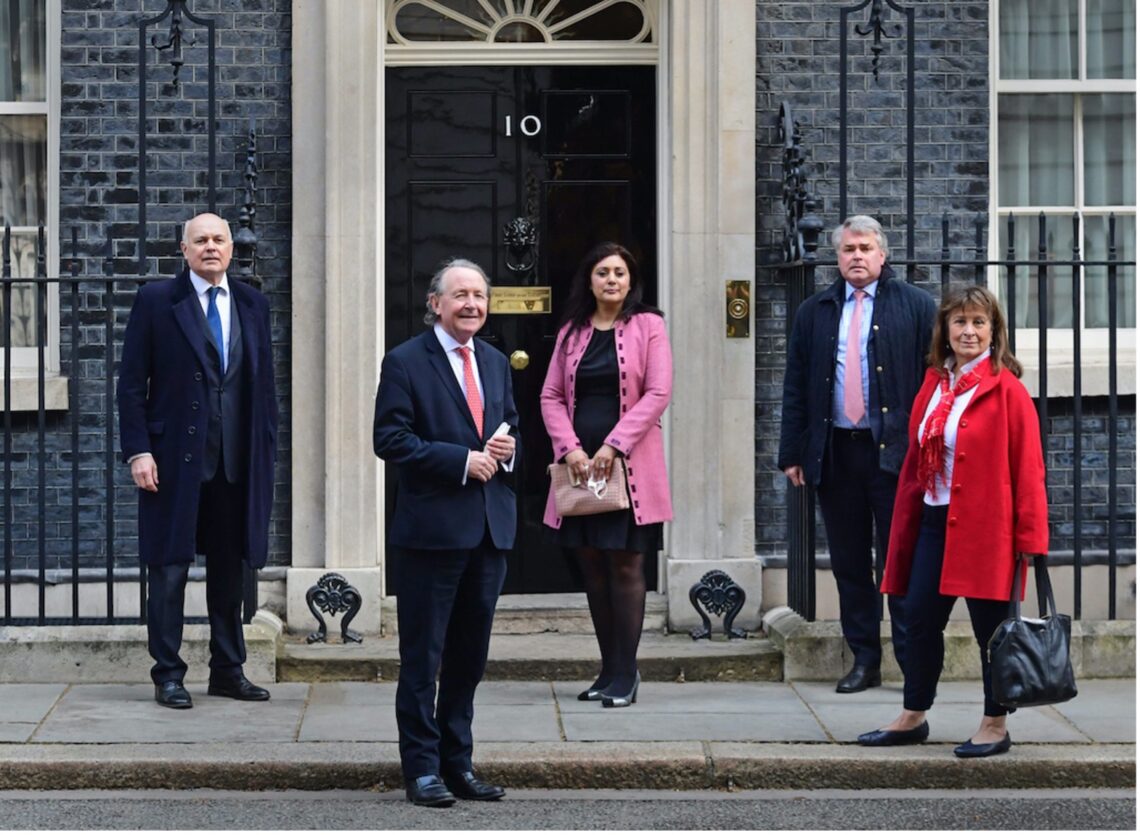

To the EU’s surprise and dismay, the Chinese side responded forcefully, as if to say, “If you punch me once, I’ll punch you back three times.” Only minutes after the European sanctions were announced, Beijing blacklisted five members of the European Parliament and five other officials with their families, who were prohibited from entering China, Hong Kong, and Macao. Also, four institutions on the EU side have been sanctioned. Officials and entities in the UK, U.S. and Canada were sanctioned as well.

Radically different perspectives

Beijing’s political motivation for this countermove can be traced to the exceptional relationship between Chinese President Xi Jinping and the top Chinese Communist Party (CCP) official in Xinjiang.

Chen Quanguo, the autonomous region’s party secretary, had been entrusted by the supreme leader to tackle the problem of “the three forces” (terrorism, separatism, extremism). The central government supports this effort with significant resources: nearly 400 billion yuan ($60 billion) from the central government and more than 15 billion yuan ($2.25 billion) from local governments are allocated to the autonomous region every year.

Secretary Chen claims that his personally designed campaign, launched in 2016, has turned Xinjiang into “one of the most successful human rights stories” in China. The government is preparing to expand it to other regions in the country. This crisis management “success” made Mr. Chen a confidant of President Xi. In October 2017, at the 19th CCP congress, the secretary was elevated to the inner circle of power in the country, becoming a member of the Central Politburo. In 2022, during the 20th congress, he is expected to jump even higher – into the Politburo Standing Committee.

When the sanctions came in March, President Xi was left with no ground to stand on in the party.

In the eyes of President Xi, the EU sanctions that depict the Xinjiang experiment as a crime are an attempt to taint a policy masterpiece that he has supervised personally. That, of course, angered the president.

Also noteworthy was the fact that late last year, Mr. Xi endorsed a speedy signing of the EU-China investment agreement, seeing in it a pro-China shift by the Europeans, swayed from the U.S. orbit under his “guidance.” The Chinese side bit the bullet and made significant concessions to clinch the deal. They were sure it would work for China, as the EU badly needs its vast market, and the pandemic has only deepened the dependence of many European companies on China’s business.

The logic was simple: European companies needed the lifeline of China markets, so the EU was bound to adopt pro-China policies. The CCP advertised CAI among its ranks as a policy breakthrough and another proof of the top leader’s diplomatic acumen. When the sanctions came in March, Mr. Xi was left with no ground to stand on in the party. His response was, “Since you started to smash things, I will smash more than you.”

The fallout of the confrontation

Their hurting pride aside, the Chinese leaders must have considered various consequences of their response to the EU’s modest move; for example, the countersanctions could make CAI’s future even more uncertain. Since the deal was in negotiations for seven years, reactions in Europe were mixed.

However, the Chinese side believes that Germany and Europe’s other industrial states are more anxious than China to get the CAI passed early. If this happens, European companies in China will be able to free themselves of the straitjacket of government-imposed joint ventures and begin to function as wholly foreign-owned enterprises. The German carmaker Volkswagen that operates a large plant in Shanghai, for example, has declared its readiness to invest billions of euros into electric vehicle production there if CAI is ratified. The second VW plant would churn out electric cars and rival Tesla Inc.’s base in the city.

The Chinese automakers that benefit from their joint ventures with VW, BMW and Mercedes-Benz are begging Beijing to maintain the status quo or give them a cushion period because their technologies are still no match for those of the foreign partners. Chinese companies will not complain if the CAI ratification process is delayed.

Those who dare challenge Chinese interests, as defined by the CCP, can face serious consequences.

President Xi doubled up in the sanctions game also because of his firm belief that the West is already past its prime while China will be number one in the world soon. This cocky attitude is most evident in the ramping up of China’s so-called wolf-warrior diplomacy.

China vilified the West in 2020 on such matters as the origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus (alleging it had come from Western military labs). Yet, Beijing has not been trying to spawn political change outside China. This year it has begun, however, to attempt to interfere with the West’s civil society organizations and scholars – such as those at the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), Europe’s leading think tank in the field – and intimidate those who show China in a bad light.

The message to the West is clear: democratic liberties and academic freedom do not apply to matters important to China. Those who dare challenge Chinese interests, as defined by the CCP, can face serious consequences. Again, this marks a deciding turning point in the EU China strategy

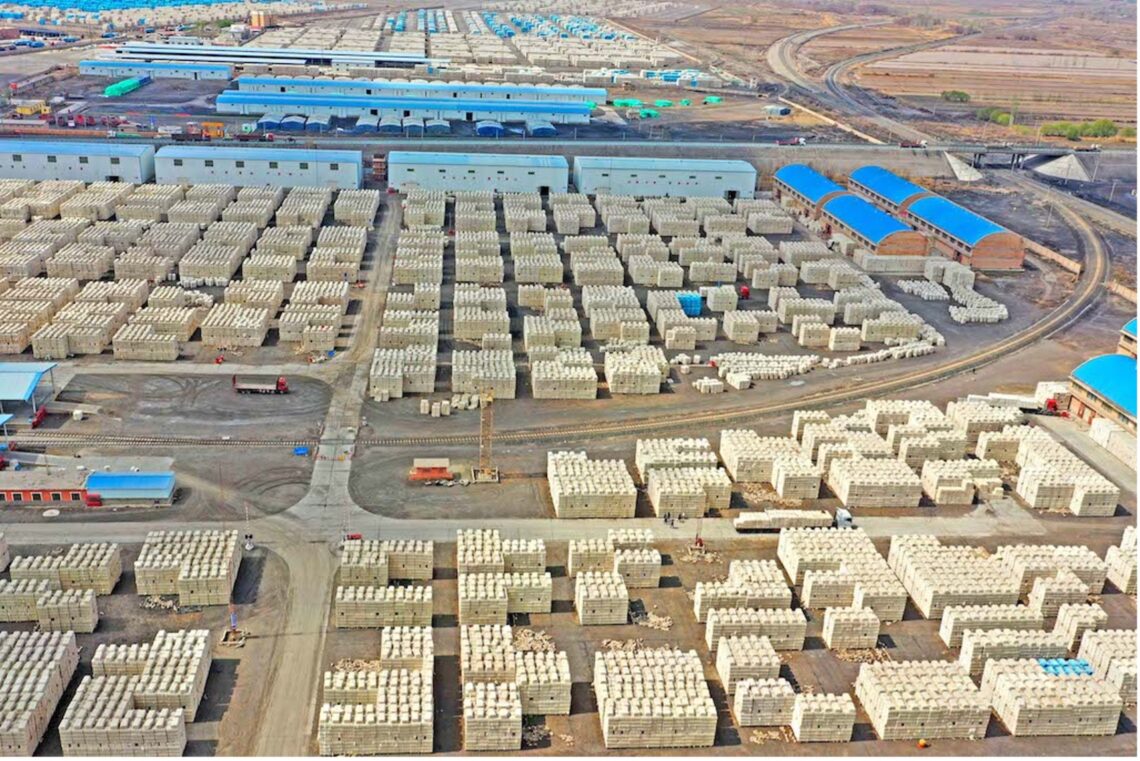

China’s cotton business: a pivotal factor in the EU China strategy

The above rule extends to the economic realm, even if enforcement takes a different form there. After reports of forced labor in Xinjiang hit the international media, many leading fashion brands changed their arrangements with Xinjiang-based cotton suppliers or cut ties with the region entirely. Responding to the allegation with angry denials, the Chinese government incited young consumers to launch a boycott campaign against Western brands such as H&M, Adidas, Lacoste, Ralph Lauren, Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger and the like.

Notably, this campaign is different from the previous boycotts of Japanese products, South Korean appliances or Carrefour stores. Firms such as H&M and Nike sell their wares in China, but significant parts of what comes off their assembly lines in that country are exported. And this is where the Better Cotton Initiative (BCI), a nonprofit governance organization with more than 2,000 participating companies, comes into play.

The organization runs the world’s most extensive cotton sustainability program and sets benchmarks for the industry’s standards including corporate social responsibility (CSR). However, China categorically prohibits any foreign companies from banning products such as Xinjiang cotton on human rights grounds. As a result, Beijing is trying to create its own standards and set up a competing association called Future Cotton.

The boycott campaign hurt many companies enough to make them bow to Beijing. To avoid further trouble, the BCI website removed its 2020 report on forced labor in Xinjiang and the call for boycotting its cotton. The organization stands by its CSR standards, but it is not clear how long it will be able to do so in China.

Germany may play a considerable role in the search for a way out of the dead end.

International companies that are less dependent on China’s domestic market, however, have started reevaluating their business environment and considering moving their supply chains elsewhere. Many Western companies have already postponed their expansion plans in China, and a few are already transferring their manufacturing operations to other countries.

Seeking a way out

The mutual sanctioning caused much tension between the EU and China, thereby putting unprecedented pressure on the EU-China strategy. The rupture can only heal over time. One thing is certain: both sides need each other, and they seek solutions.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and President Xi spoke on the phone on April 7, some two weeks after the crisis started. According to the Chinese foreign ministry’s official statement, it was the chancellor’s initiative. Indeed, Germany may play a considerable role in the search for a way out of the dead end. The CAI has given its industrial sector and its chancellor a good deal of hope; Germany relies heavily on China for trade. And in the view of the CCP, Germany and France are anti-American, which creates openings and opportunities for China.

At the same time, President Xi apparently does not see the EU as a mature political organization. During the phone call, he expressed hope that the Europeans would “make correct judgment independently” when the EU-China strategy is facing “various challenges.” These remarks show Mr. Xi’s determination to prevent Europe from joining the U.S-led coalition of democracies ready to challenge China on such issues as human rights and territorial disputes. China’s leader appears to believe that the EU’s participation in the collective sanctions was due to U.S. pressure.

That phone conversation shows Berlin and Beijing are straining to protect their mutual relationship. President Xi may be ready to give up on the EU, but he does not want to “lose” Germany – one of the few countries remaining in the Western world that make significant technology transfers. And China has been Germany’s largest trading partner for five consecutive years.

The next round of Sino-German governmental consultations, held since 2011, remains on the schedule. Also, both sides are looking forward to celebrating next year’s 50th anniversary of their diplomatic relations. The event may give some insight into how Ms. Merkel’s successor will handle this relationship.

In the meantime, China is also making quiet efforts to ease the tension. At the peak of the boycott, Premier Li Keqiang paid visits to companies in the supply chain of the Western fashion firms involved in the conflict, signaling the government’s desire to retain Western capital invested in China. But Beijing’s interest in Western business and technologies notwithstanding, China is indifferent to the EU’s Xinjiang human rights grievances.

France, too, has been trying to ease the atmosphere. President Emmanuel Macron attended a climate video summit with the Chinese and German leaders on April 16. The event’s timing deliberately preempted the launching of the U.S. climate cooperation meeting with China.

China sees its policy in Xinjiang as a success; the EU sees it as a blatant human rights violation.

U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry was very coldly received in Shanghai when he landed on April 14 as part of the preparations for President Biden’s virtual climate summit later in the month. That was in stark contrast to how China treated the meeting with the leaders of Germany and France.

A possible solution to the sticky situation related to Xinjiang

China sees its policy in Xinjiang as a success; the EU sees it as a blatant human rights violation. There seem to be only two ways to solve this problem. Beijing could allow an independent investigation in the province by either the United Nations or the EU. However, in today’s China, where national sovereignty trumps all other concerns, the likelihood of the government approving a fully independent investigation is slim.

Another approach, a more promising one, is creating at least a measure of mutual understanding. The EU could adopt a more neutral stance on the origins and outcomes of the Xinjiang issue. If, for example, the Europeans continued not to use such loaded terms as “genocide” and “concentration camps” in their rhetoric and added a clear condemnation of terrorist acts in the province, China’s political elites might reciprocate with some moderation. According to official figures, in Xinjiang, 615 people died in so-called terrorist incidents (presumably including the suppression of terrorist groups) between 1990-2016. Unofficial sources give much higher numbers of casualties. And arguably, integration in a huge multi-ethnic country is not an easy task.

The Chinese authorities rely on repression, intimidation, indoctrination, surveillance and material inducements in their pursuit of multiethnic “modernization.” The policy is no different from the official approach to dissidents among the Han Chinese. (Undeniably, minorities face the additional problem of cultural and religious alienation.) It is hard to imagine that outside sanctions will change the authorities’ modus operandi fundamentally.

Scenarios

The West’s optimistic scenario (probably too good to be true)

China could reluctantly adapt to the carrot-and-stick strategies of the West. The EU, like the U.S., would link gradually its industrial and trade policies to human rights issues. Beijing would abandon its attempts to intervene in the activities of academic and legal institutions in the West. The EU China strategy entails close cooperation on mitigating climate change. The investment agreement would be ratified by EU member countries and implemented during 2022, primarily due to a strong political push from Germany and France. EU member states, and especially the German industry, would reap the benefits of CAI. However, this would not stop China’s ongoing efforts to acquire advanced Western technologies by any means.

Also, the EU would come to accept that China will not give up on its system of subsidies and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in plotting strategies for its economy. These are critical devices in Beijing’s economic policy toolbox. Chinese companies, especially SOEs, would continue to rely on the state’s help after CAI is implemented, particularly when it comes to investments in cutting-edge technology areas via mergers and acquisitions of European companies.

But even in those circumstances, the G7 countries that have vowed recently to take joint action to halt China's “harmful industrial subsidies and other business practices that hinder market competition” would discover that this is a tall order. Even a fully functional CAI would not solve all the problems of China’s preferences for subsidies and other contentious matters.

A less rosy picture of the future

Chinese leaders could stick to their guns. They would continue defying new EU-China strategy. Beijing’s propaganda attacks and intimidation attempts in Europe would continue unabated. The CAI would fall victim to the deteriorating political environment and would not be ratified. China would resort to its plan B and reach out directly to big European companies, offering them incentives to continue business as usual, at the same time ridiculing the EU’s “incompetence.”

As a result of the political confrontation and technological “decoupling” between the U.S. and China, European companies would be faced with a choice between two markets, two supply chains and competing technical standards. The pressure in the European industries to compromise and help the Chinese side meet its technological needs would keep increasing.

The EU’s strategic position has already been undermined by China’s consistent policy of establishing economic and political footholds in Europe. Since 2013, China has bought significant shares in 14 European ports. The Republic of Montenegro in the Balkans, a candidate for EU membership, is gasping for breath under the crushing weight of its debt to China. Also, in 2019 Italy agreed to join President Xi’s ambitious and very political Belt and Road connectivity project without as little as consulting with Brussels. And lately, Serbia and Hungary often seem to act like Beijing supporters.

This step-by-step encroachment policy is likely to continue in the coming years. And Chancellor Merkel, who has had a great influence on the EU decision making, could be replaced by a true supporter of her policy but lacking much sway in the EU. In that case, the EU could be marginalized. The relations resulting from the new EU-China strategy would give way to bilateral contacts between China and individual European states and their companies.