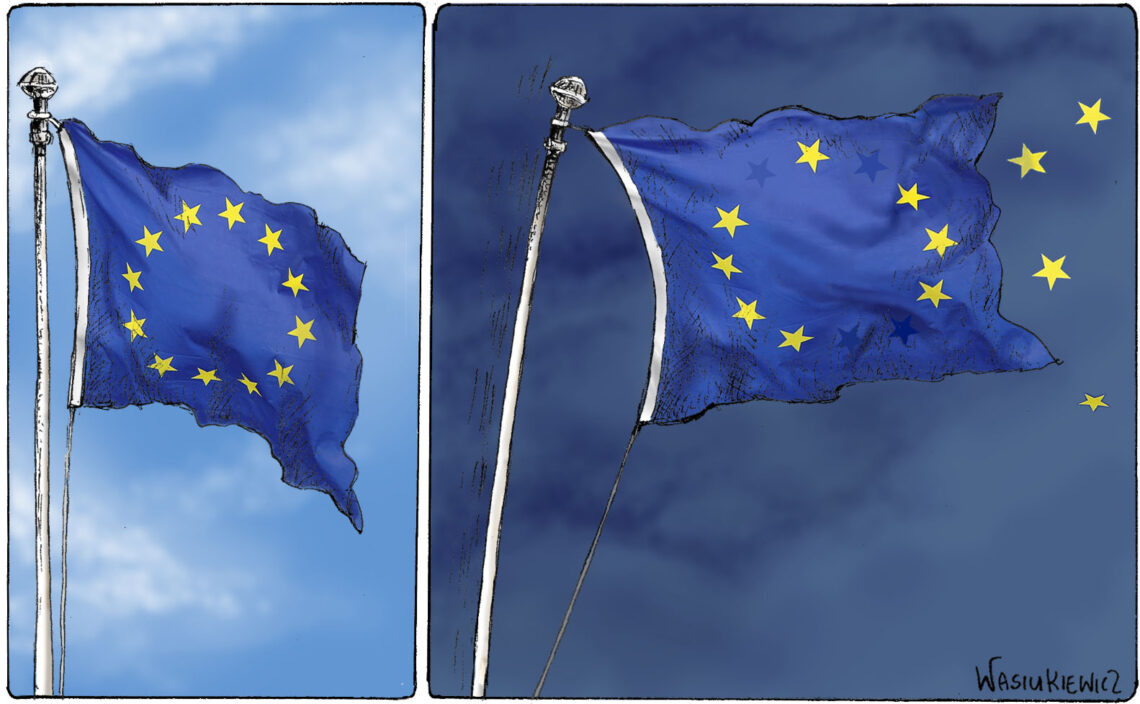

Emerging contours of a weakened Europe

Covid-19 has had a profound effect on Europe, not only bringing changes that no one thought possible just months ago but deepening divisions and intensifying acrimony between EU countries. With these ruptures laid bare, the bloc again faces an existential crisis.

In a nutshell

- The Covid-19 crisis has weakened the legitimacy of EU institutions

- Countries are fending for themselves at the expense of partners

- Divisions between member states are deepening

This report is part of a GIS series on the consequences of the COVID-19 coronavirus crisis. It looks beyond the short-term impact of the pandemic, instead examining the strategic geopolitical and economic effects that will inevitably be felt further in the future.

During the memorable month of March 2020, Europe was transformed in ways that no one would have believed possible just a few weeks before. The coronavirus outbreak had all the trimmings of a classic black swan event. Beyond the enormous economic consequences, the crisis will likely bring severe political disruptions. Many governments will be held to account for having been ill-prepared and for having wasted valuable time before taking decisive action.

When the crisis erupted in China, Europe watched in bewilderment as Beijing imposed draconian measures to contain the virus. The conventional wisdom was that such actions would be unthinkable in Europe. Populations used to open societies and democratic government would simply not tolerate the restrictions. At the outset of March, that was still the general belief. By the end of March, most of Europe was on lockdown, with at best hazy notions of when normalcy might return.

By then, the political agenda had become focused on how to restrain the spread of the virus without triggering economic depression. As the number of new infections grew, the previously “existential” problems of the European Union disappeared from public discourse. Brexit, the rise of populism and even negotiations about a new budget were seemingly not on anyone’s mind.

Jacques Delors warned that if the EU failed to unite it would face not only a health crisis but an existential threat.

Looking forward, the main question is what European consolidation might look like after the coronavirus crisis. Will it be possible to resurrect the vision of “one Europe whole and free”? Or will the outcome be a deeply fragmented continent, marked by border controls, resentment between EU member states, nationalist outrage against migrants and a proliferation of authoritarian government?

Loss of legitimacy

At the end of March, the widely respected former European Commission President Jacques Delors, aged 91, issued a stark warning. Should the EU fail to unite in the face of the public health disaster, it would suffer a crisis far worse than the euro crunch and the refugee chaos, he said. He had good reason to express such concern.

The EU had been shown to be if not irrelevant then at least a spectacular no-show. As borders were being closed, the fundamental principle of free movement was cast aside. Brussels did manage to ensure that borders would remain open for the movement of goods, but despite recommendations to the contrary from the World Health Organization, most countries closed their borders for the movement of people.

Even worse for the legitimacy of the EU was that several member states moved so quickly to protect their national interests by imposing prohibitions on the export of crucial medical supplies. Again, Brussels managed to roll back some of the restrictions and to restore the free movement of goods. However, the belief in a common market of reliable suppliers has likely taken a serious hit.

When EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen finally tried to exert some leadership by calling for a discussion on an exit strategy from the lockdowns, she immediately took heavy criticism from some of the worst-hit countries, including, significantly, France.

The uneven damage the virus has wrought on countries and the barely perceptible willingness of those in better shape to help the worst afflicted will mar prospects for restoring a climate of cooperation across Europe. It was telling that despite the extreme gravity of the situation in countries like Italy and Spain, EU leaders took ample time to hammer out a rescue package.

Although the numbers involved are mind-boggling, interpretations of the package’s deliberately woolly wording have varied. Spain and Italy want the EU to issue debt in the form of special “coronabonds,” yet Austria, Germany and the Netherlands oppose the move. Memories of animosity over the euro crisis bailouts have come back to haunt relations between north and south.

While Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte has warned that the COVID-19 crisis could cause the EU to fail, opposition politician Matteo Salvini threatens to force that very outcome. Never much of a friend of Brussels, he has intensified his rhetoric, referring to the EU as a “den of snakes and jackals.” Once the crisis is over, he will likely campaign for a return to power of his Lega party on a virulent anti-EU platform, potentially even calling for an Italian exit.

Though the likelihood of Italy leaving the EU – triggering a collapse for the European project as a whole – is probably remote, the enmity is indicative of how challenging it will be to restore a semblance of unity of purpose.

Less clout

When Europe emerges from the coronavirus crisis, the landscape will look fundamentally different than it did at the outset of 2020. Most importantly, the EU’s geopolitical clout will have taken a serious hit. With the United Kingdom likely having left the EU without a deal, and with government debt having spiked in countries across the continent, Brussels will find it difficult to stand up to a resurgent China.

Beijing has already shown a desire to pull individual countries away from the EU. Lately, it made a big splash sending emergency medical aid to Italy. Although Russia would surely love to follow that lead, its own domestic problems will probably constrain the Kremlin’s ability to execute its strategy of divide and conquer. In contrast, the threat that China will increase its footprint in Europe is considerable.

Other factors will exacerbate European weakness. Some governments will receive a boost in legitimacy from having taken speedy, successful action to combat the virus, while others will face heavy criticism for having been too slow. The quality of governance will decline, probably precipitously so.

Beijing has already shown a desire to pull individual countries away from the EU.

A key question will be how much verve is left in the Franco-German tandem. While France will surely work to resume leadership, its insistence on protecting itself before coming to the aid of its southern neighbor will taint Paris’ ambition. In Germany, the question of who will succeed Angela Merkel as chancellor will remain an open issue, making her a lame duck and adding to confusion over Berlin’s role.

In Central Europe, Hungary will feel vindicated in its early insistence on closed borders and ethnic homogeneity. By mid-April, Hungary had only 1,579 confirmed cases and 134 deaths, with a daily rate of new infections in the dozens. These figures stood in stark contrast to the frightening numbers recorded in core EU member states like France, Germany and Italy. Prime Minister Viktor Orban had no problem securing emergency powers from parliament that allow him to rule the country by decree indefinitely.

A ruling by the European Court in early April determined that in refusing to accept migrant quotas, Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic had broken EU law. If Brussels keeps trying to impose penalties for these offenses, it will deepen resentment and prompt the governments of Poland and Hungary to lock arms.

In the Nordic region, Sweden will face the consequences of its long-standing practice of moral grandstanding, of its contrary policy of open borders, of welcoming asylum seekers and of implementing minimal restrictions to combat the coronavirus.

Nearby countries had already watched in shock as Stockholm’s open-migration policy led to a significant rise in violent crime. Denmark even introduced border controls in 2019. In 2020, the spread of the coronavirus prompted Sweden’s neighbors to swiftly close their borders. Unperturbed, the Swedish government still allowed flights from heavily infected Iran to land, with no passenger screening upon arrival.

Patching the wounds

These illustrations – of a widening rift between Europe’s north and south, a sputtering Franco-German tandem, growing estrangement between Central Europe and Brussels, and deep divisions within the Nordic region – show just how hard it will be to put Humpty Dumpty back together again.

The challenge will be to convince member states that it should be trusted to prevent renewed export restrictions if need be.

One case in point is whether Brussels can build EU-wide policies to prepare for the next pandemic. The challenge will be to convince member states that it should be trusted to prevent renewed export restrictions if need be. The countries that can build their own capabilities will be more likely to follow the UK’s lead in doing so.

Another challenge is border controls. Although the jury is still out on whether closed borders have helped slow the virus, there can be little doubt that the measure has caused a serious drop in organized crime, as international gangs can no longer move drugs, trafficked people and criminal loot freely across borders. Some countries will likely be hesitant to reopen the sluice gates for such activities.

A third challenge will be to deal with resurgent nationalism. If it turns out that poorly integrated and severely overcrowded migrant communities have added to the spread of COVID-19 infections, then this will provide a boost to anti-immigrant parties across the continent, from Lega in Italy to the National Rally in France and the Alternative for Germany (AfD).

With so much on its plate, the European Commission’s biggest challenge will be to convince member states that giving it even more money is the best way to provide security and prosperity for all. It promises to be a hard sell indeed.