Averting a full-blown gas crisis in Europe

European gas markets ended 2022 in much better shape than they had been during the catastrophic first quarter. But they are not out of the woods yet.

In a nutshell

- Gas prices fell in Europe by the end of 2022; many hope the worst is over

- Governments across the EU adopted measures to reduce consumption

- Also, the EU focused on filling its gas storage ahead of winter

- Gas supplies from the Americas, particularly the U.S., saw a big increase

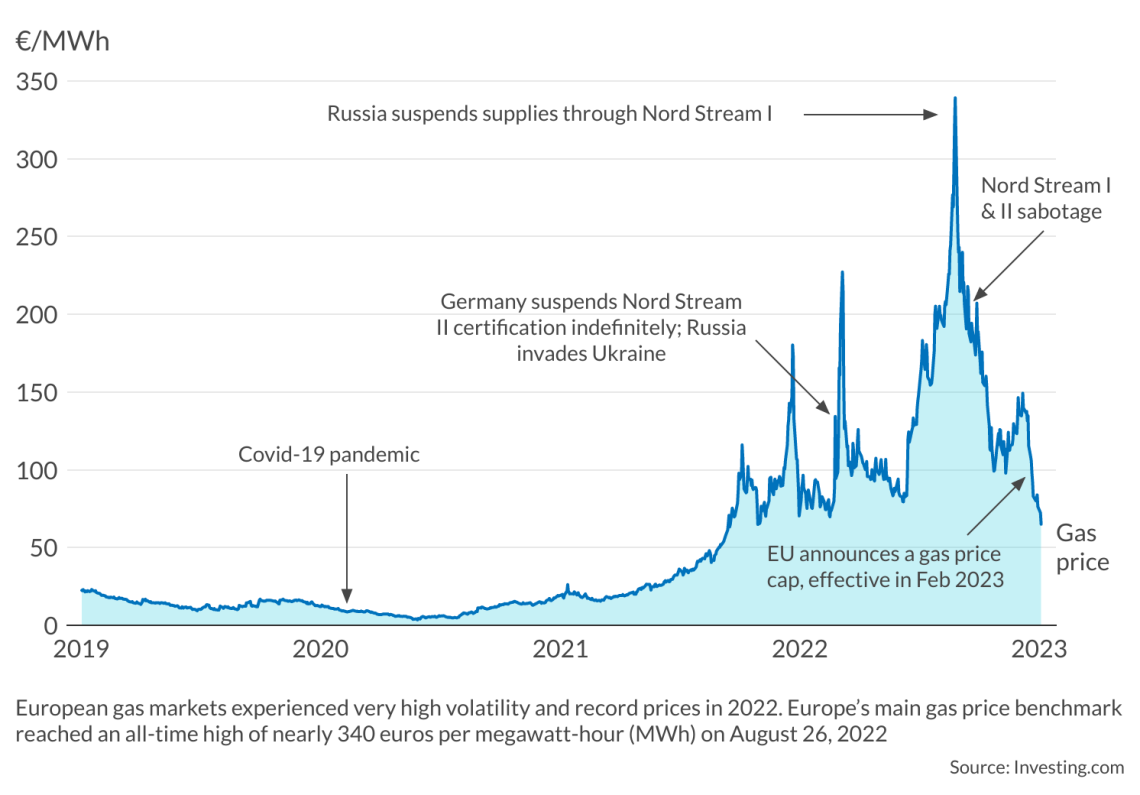

The year 2022 was terrible for European gas markets, with notable volatility and record gas prices. The Dutch Title Transfer Facility (TTF), the continent’s leading gas price benchmark, reached an all-time high of nearly 340 euros per megawatt-hour (MWh) on August 26, 2022 – an increase of more than 320 percent compared to the beginning of the year and 640 percent compared to August the previous year. Prices then fell by almost 340 percent by the end of the year.

Cocktail of coincidences and gas market evolution

This roller coaster led to an annual average price in 2022 that was six times the 2017-2021 average (around 23 euros per MWh), resulting from a cocktail of factors happening simultaneously. Some were unusual coincidences, such as the heat wave and drought, which limited the supplies of alternative sources to natural gas (primarily hydropower in Norway) and affected nuclear power generation in France, which had to shut down some of its reactors due to planned or emergency maintenance.

Other factors were part of the natural evolution of gas markets, with the growth of liquefied natural gas (LNG) connecting hitherto disconnected markets. In that respect, the high demand in Asia during the winter of 2021-2022 attracted more LNG supplies to the region and subsequently put upward pressure on European prices as supplies tightened.

However, the geopolitical factor and the subsequent politicization and weaponization of natural gas have played the biggest roles. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 opened a new chapter in both regional and global markets, as the European Union’s most important gas supplier for decades deliberately curtailed its exports to the continent in response to sanctions, while the EU embarked on a frenzy to replace that loss and fill its storage ahead of the heating season.

Read more of Europe's gas saga

Europe turns to Algeria for natural gas

So far, European gas markets have started 2023 on a surer footing; many believe the worst is over. As a regulator, Germany’s Federal Network Agency put it, a gas shortage is increasingly “unlikely,” with the situation less tense than at the beginning of the winter. Nonetheless, gas markets are still in a high-price environment, and volatility is expected to continue, albeit probably less dramatically than what we saw last year. The situation remains precarious, but a full-blown crisis may have been averted.

Facts & figures

Warm spell to the rescue

Several factors that have shaped European gas markets last year, especially since the summer, can help clarify their likely course this year.

One of the essential applications of natural gas is in space heating, and subsequently, gas demand is seasonal, typically increasing in winter. The warmer-than-usual weather that Europe has experienced since last autumn has been a blessing for the region. Many European cities saw record-high temperatures, particularly in December and January.

According to the World Meteorological Organization, Dresden-Hosterwitz in Germany experienced 19.4 degrees Celsius on December 31 last year, breaking the record of 17.7 degrees last seen on December 5, 1961, while Warsaw, Poland, saw 18.9 degrees on January 1 this year compared to the previous record of 13.8 degrees recorded in January 1993. Bilbao in Spain hit 25.1 degrees on the first day of 2023, edging out the previous January record of 24.4 degrees just in 2022, rendering obsolete the government emergency measure announced in August last year that prohibited heating to be set above 19 degrees.

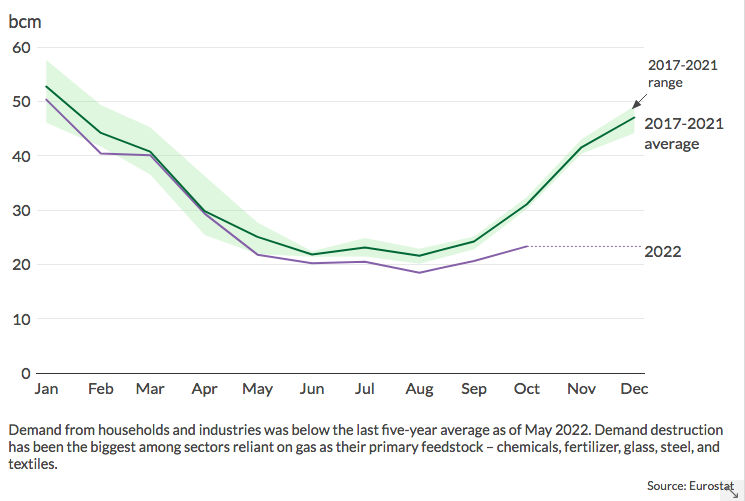

Even a slight temperature variation can significantly impact gas demand and prices. A study on the United Kingdom’s gas market estimates that a 1 degree Celsius reduction in daily temperature typically gives up to a 4 percent increase in gas demand. According to the think tank Bruegel, European demand in October 2022 was 27 percent, in November 24 percent, and in December 13 percent lower than the previous year, partly attributed to the warmer weather.

Significant demand destruction

Demand from households and industries reacted to the elevated prices and has been below the last five-year average as of May 2022. One International Monetary Fund (IMF) study estimates that demand destruction is likely to prove more significant among industries such as chemicals, fertilizer, glass, steel and textiles – all highly reliant on gas as their primary feedstock – than in households. Those industries are exposed to global competition; they are thus more sensitive to an increase in the cost of gas and are forced to respond by cutting production and gas use.

Governments across the EU also adopted several measures to reduce local consumption, including switching off streetlights and hot water in public buildings. The EU agreed on a joint target to cut gas consumption by 15 percent between August 2022 and the end of March 2023, compared to their average consumption in the past five years. The efforts are paying off.

Qatar builds up its gas muscle

It is still being determined how much of that demand is structural and therefore permanent, hence unlikely to bounce back if prices decline. But those who invested in non-gas boilers because of the crisis are unlikely to switch back once gas prices fall.

Facts & figures

Critical EU success: nearly full gas storage

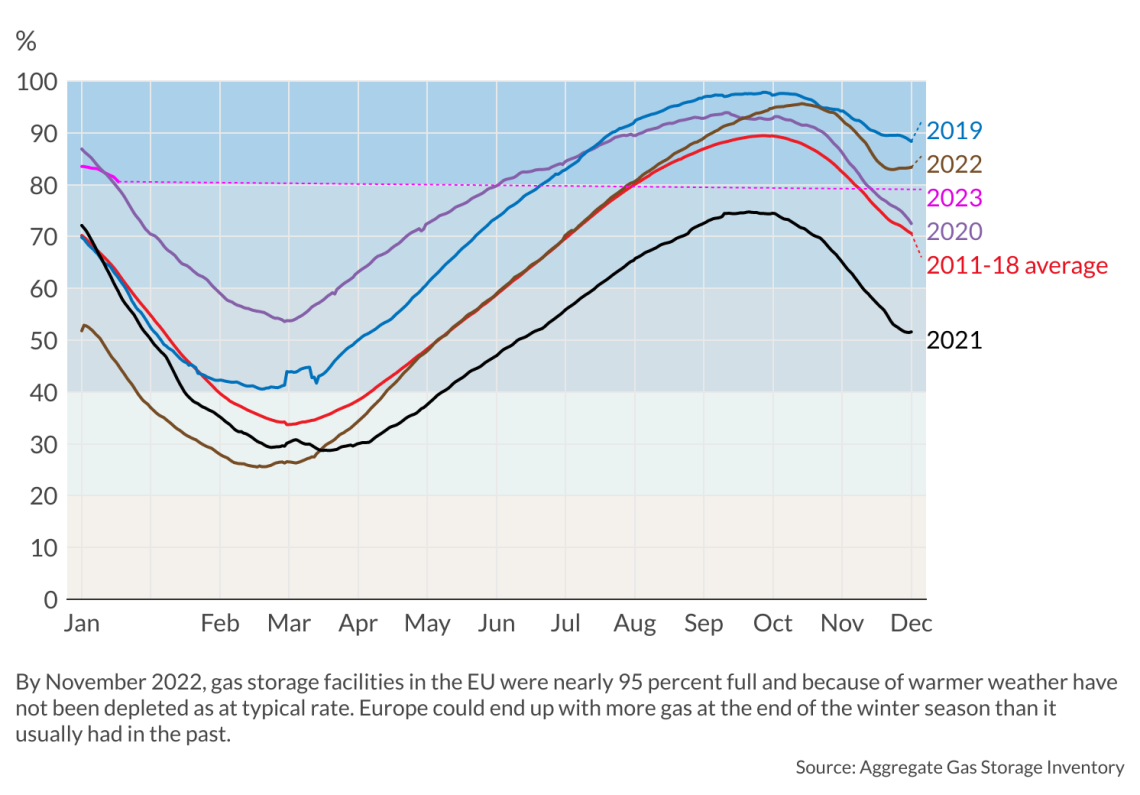

Weaker demand means less drawdown on storage, which plays a vital role in balancing markets during winter because they are used as a buffer at times of high demand and potentially tight supply.

Fearing the risk of supply disruptions soon after Russia invaded Ukraine, the EU aggressively focused on filling its gas storage ahead of winter. This fear partly explains the rapid increase in prices up to summer 2022, especially since 2021 storage levels across the region were well below the typical levels. At the beginning of 2022, they were hovering at only around 50 percent, compared to 75 percent the previous year.

By November 2022, EU gas storage levels hit nearly 95 percent, allowing the EU to enter the winter season with a larger buffer. Furthermore, because of the warmer weather, European gas storage levels have not been depleted as one would normally expect. Depending on the weather during the coming few weeks, Europe could end up with more gas at the end of the winter season than usual, thereby avoiding a repeat of last year’s frenzy.

Facts & figures

Crowded gas terminals in Europe

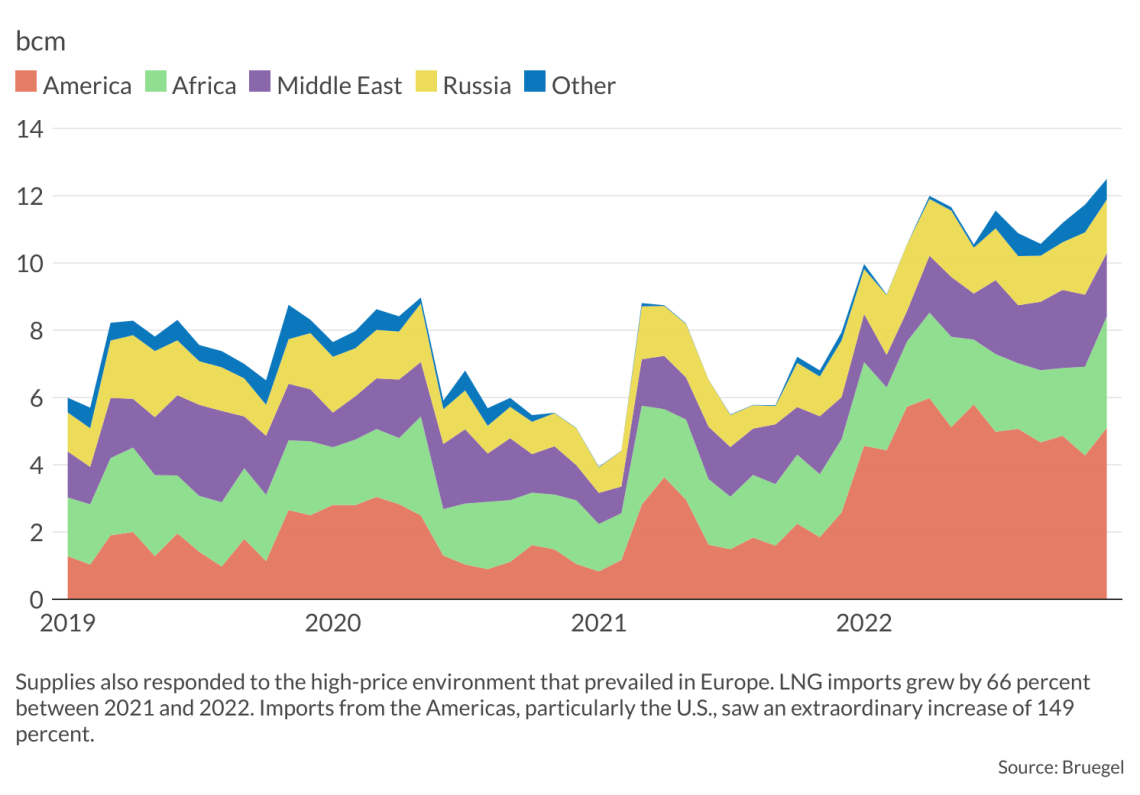

Supplies also responded to the high-price environment that prevailed in Europe. LNG supplies grew by 66 percent between 2021 and 2022, reaching a record level of 132 billion cubic meters (bcm) – or around 40 percent of the EU’s gas imports (compared to 23 percent in 2021).

Supplies from the Americas, particularly the United States, saw the biggest increase (149 percent) to reach 61 bcm. LNG exports from other suppliers increased as well: 24 percent from the Middle East and 19 percent from Africa. But the most controversial increase has been from Russia (36 percent), which is still clinging to its most important market – that is, Europe – but gradually shifting from pipeline to LNG trade, giving it greater flexibility to target different markets.

Facts & figures

The influx of LNG toward Europe faced limited import capacity, which resulted in congestion around existing terminals. In October, 60 LNG ships (10 percent of the global LNG fleet) were waiting to unload their cargo.

Norway’s oil fund braces for climate challenges

Should the EU expand its LNG import facilities, gas supplies will likely respond faster to market signals. Germany, which until last year did not have such a facility, announced it would invest in two permanent land-based import terminals while leasing five floating units to be deployed starting from the end of 2022. The country’s ability to build a floating LNG terminal in the northern port city of Wilhelmshaven – in a record-breaking time of fewer than 10 months – clearly shows that infrastructure can be developed if the political will is there to facilitate it.

Europe is not out of the woods yet

China’s zero-Covid policy was a blessing in disguise for Europe as it helped keep Asian gas prices more tamed compared to what European markets saw, thereby supporting the flow of LNG toward the latter premium market. However, the sudden abandonment of that policy in December 2022 has left many in Europe fearing a strong rebound in Chinese demand for various commodities, particularly energy.

Depending on whether such a scenario materializes and when it happens, Europe may be up for stiff competition for the same pool of supplies. LNG supplies take time to increase, given the capital intensity of the investment. Already the Asian Japan Korea Market (JKM) benchmark is at a premium to Northwest European LNG for every remaining month in 2023, according to S&P Platts.

LNG, which is untied to long-term contracts (the so-called spot LNG), will go to the highest bidder. Europe, however, introduced a gas price cap as of February 15 this year. That cap may be a disincentive to potential suppliers should a higher price be registered in other markets. The price cap is triggered if prices exceed 180 euros per MWh for three days on the TTF gas hub’s front-month contract. Had this cap been applied early last year, Europe would have faced a challenge filling its storage facilities.

Russia remains in the gas game

Despite the geopolitical developments of last year and the EU’s determination to move away from Russian gas, Russia continues to be an important gas supplier to Europe, providing around 17 percent of the EU’s gas import needs, both by pipeline and LNG.

The International Energy Agency has warned that if Russia fully shuts down its pipeline gas supplies and China’s LNG imports recover to their 2021 levels, the EU could face a gas shortage of around 57 bcm. The gap could be reduced by around 30 bcm with additions in renewable energy capacity, hydro and nuclear output recovery and consumer-led behavioral changes to reduce energy consumption. That leaves the EU with a 27 bcm gap, which can be closed by behavioral changes, efficiency gains and other renewable energy measures, the agency added.

However, given the various unknowns, including the weather, it is nearly impossible to estimate. There is also the economic outlook, which for now looks gloomy. The IMF downgraded its 2023 gross domestic product (GDP) growth forecast in the euro area from 1.2 percent to 0.5 percent in its October 2022 Economic Outlook, stating that “continued uncertainty over energy supplies has contributed to slower real economic activity in Europe, particularly in manufacturing, dampening consumer and, to a lesser extent, business confidence.” A shrinking economy leads to weaker demand.

Several factors – some voluntary measures but mostly simple market mechanisms – have helped the EU avert a full-blown crisis. It is not easy to suddenly sever a decades-long relationship with Europe’s biggest supplier, especially if that relationship relies on pipelines that, by nature, link both supplier and consumer in a lengthy, mutual interdependence.

Europe is not out of the woods yet. However, the region has already initiated several tangible measures to limit the vulnerability of its long-established exposure to Russia, which has not hesitated to exploit that vulnerability. Should the momentum be maintained, and markets allowed to function with limited government intervention, Europe may be in a better place in the longer term, with bumps being the norm along the journey.

Facts & figures

Gas facts

- Fertilizers Europe, a European association of 17 fertilizer manufacturers, warns that 70% of the European production capacity of fertilizers has been curtailed due to high gas prices.

- By December 2022, EU27 gas stocks experienced the smallest depletion since the heating season started on October 1.

- During August-November 2022, natural gas consumption dropped beyond the 15% target in 18 member states, including Finland (-52.7%), Latvia (-43.2%) and Lithuania (-41.6%), according to Bruegel.

- In 2021, China surpassed Japan as the world’s largest importer of LNG.

- Pipeline gas deliveries to the EU bloc dropped by 20% year-on-year. That was primarily due to Russian supplies, which plummeted to around 66.6 bcm or less than half of the supplies sent in 2021 (Kpler).

- Total EU fiscal support was nearly 3% of GDP in 2022, much of which followed the Ukraine energy price surge (Allianz).