The void of German politics

German politics have reached an unprecedented level of incoherence. With no clear source of leadership, the situation is likely to worsen in the run-up to the 2021 elections – leaving Germany in poor shape to address the pressing issues that it faces.

In a nutshell

- There are no strong candidates that could succeed Chancellor Angela Merkel

- The Christian Democrats may survive, but will need to seek new allies to govern

- The Greens are likely to become kingmakers after the 2021 federal elections

This new series of GIS reports examines how effectively countries are ruled and the consequences of governing systems for economies, societies and nations’ development prospects.

In my last year’s report on the German economy, I described the country as “the exhausted man of Europe.” The very same title could be used for this report on German politics and leadership in 2020. I expect the government to become even more debilitated, perhaps even to the brink of collapse. The party system will become even more fragmented and the overall governance system even more obstructive.

Federal exhaustion

The federal government will be mostly incapable of showing leadership in domestic and international affairs this year. Chancellor Angela Merkel announced that she would not run again in 2021, and she has already withdrawn as party leader of the Christian Democrats (CDU). As a result, she is seen by many as a lame duck. One of Germany’s leading journalists made this unflattering remark: “She hardly exists as leader of the executive. It almost doesn’t matter whether she is in India or the Chancellery. She symbolizes only herself as if she had become her own memorial. She is a world star. But is she still chancellor?”

Leadership would have required Ms. Merkel to pave the way for succession by supporting a strong candidate. Instead, the party had its members choose between three candidates, which resulted in the election of Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, a Merkel loyalist as party leader. AKK, as she is called for the sake of avoiding a tongue twister, has so far proven to be the opposite of a charismatic and visionary leader. To make things worse, she became defense minister, replacing Ursula von der Leyen when the latter was picked – by French President Emmanuel Macron, rather than by Chancellor Merkel – to become president of the EU Commission. Running and reforming the notoriously underperforming Bundeswehr is the one cabinet position that nearly guarantees failure.

Leadership would have required Ms. Merkel to pave the way for succession by supporting a strong candidate.

Hence, 2020 or early 2021 will see a leadership contest within the CDU, with Ms. Kramp-Karrenbauer perhaps holding on as party chairwoman, but not as a natural top candidate for the federal elections and thus the chancellery. At the same time, since there is no obvious CDU candidate to follow in Chancellor Merkel’s footsteps, there are rumors that the Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU) may try to push the appointment of Markus Soder, head of the Bavarian government.

Meanwhile, the CDU’s coalition partner, the Social Democrats (SPD), managed to inflict even more harm upon itself. Over the last two years, three party leaders resigned (not counting the teams of four provisional leaders). Now, party members have elected Saskia Esken and Norbert Walter-Borjans to lead the party after having rejected vice-chancellor Olaf Scholz – one of the most popular politicians in Germany, according to some polls.

Ms. Esken is a widely unknown backbencher and Mr. Walter-Borjans is a retired former state finance minister whom some remember for running unconstitutional deficits in North-Rhine Westphalia. Both are rather uncharismatic left-wingers who said (before being elected) they would want the SPD to leave the coalition with the CDU/CSU. For the time being, however, they declare their intention to test the viability of the alliance by making leftist demands for even higher taxes, deficit spending and social benefits.

Hence, there is no guarantee that the present government coalition will survive in 2020. The SPD may be tempted to provoke a dissolution, for example, by insisting on a speed limit on motorways (a highly sensitive issue in Germany), or by pushing for the expropriating of house owners, (a policy currently adopted by the SPD-led leftist coalition in Berlin).

The only reason the “grand coalition” still holds together is that it would not survive the elections otherwise. The SPD especially could face disastrous results, between 11 and 15 percent.

Hence, even if a left-wing coalition comprising the SPD, Linke (the former communist party of the German Democratic Republic) and the Greens were formed, the SPD could still end up as a junior partner under a Green Party chancellor. Fearing early elections at this stage, the SPD may, however, leave the coalition in 2020. The CDU/CSU would have to carry on with a minority government, seeking alliances with different parties on a case-to-case basis.

Party fragmentation

In 2020, only one major election will take place: the city-state of Hamburg. The outcome is likely to keep the present SPD-Green coalition government in place, with significant gains for the green party making up for large SPD losses. While Hamburg is not representative for Germany as a whole, this trend will most likely be confirmed in further polls. If federal elections were to be held now, polls predict a coalition of the CDU/CSU with the Green Party (and, if needed, the FDP).

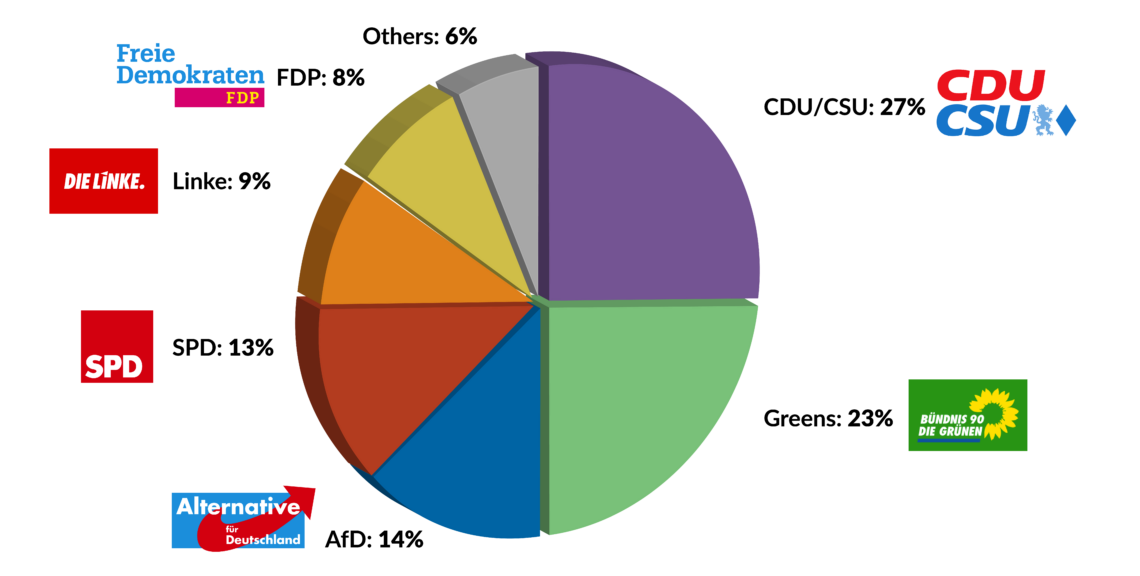

Obviously, surveys asking for whom people would vote for if elections were to happen next Sunday have limited forecasting power. There has been no election campaign yet and programs and candidates are still unknown. But the numbers indicate trends that are likely to persist this year and the next when federal elections are scheduled:

(a) The SPD is in a state of acute crisis. In the 2017 elections, it recorded its worst result in history with 20.5 percent. Now it consistently polls below 15 percent;

(b) The CDU/CSU is also bound to lose voter support (from 32.9 percent in 2017), but remains the one party most willing and able to lead a federal government – also due to its increasingly nonideological (or opportunistic) flexibility;

Driven by climate change angst, the Greens have become the new kingmakers.

(c) The Greens have become the new kingmakers: driven by a wave of climate change angst, massively supported by mainstream public media and boosted by a charismatic duo of relatively pragmatic party leaders, they could lead a left-wing coalition if votes add up, or (the more likely case) put their stamp of approval on a CDU/CSU-led government;

(d) The increasingly radicalized right-wing Alternative for Germany (AfD) may add a few votes to its 12.6 percent from the past federal elections, taking shares from both left and right. Shunned by all other parties, attacked or ignored by most media and busy with internal fights and scandals, it will remain an opposition party;

(e) The far-left Linke will remain strong in parts of Eastern Germany, with a remote chance to enter the government under a Green-led alliance;

(f) The liberal FDP is very likely to reenter parliament and may be needed to form a majority government led by the CDU/CSU and the Greens. But its appeals for pro-market policies will probably go unheard even then.

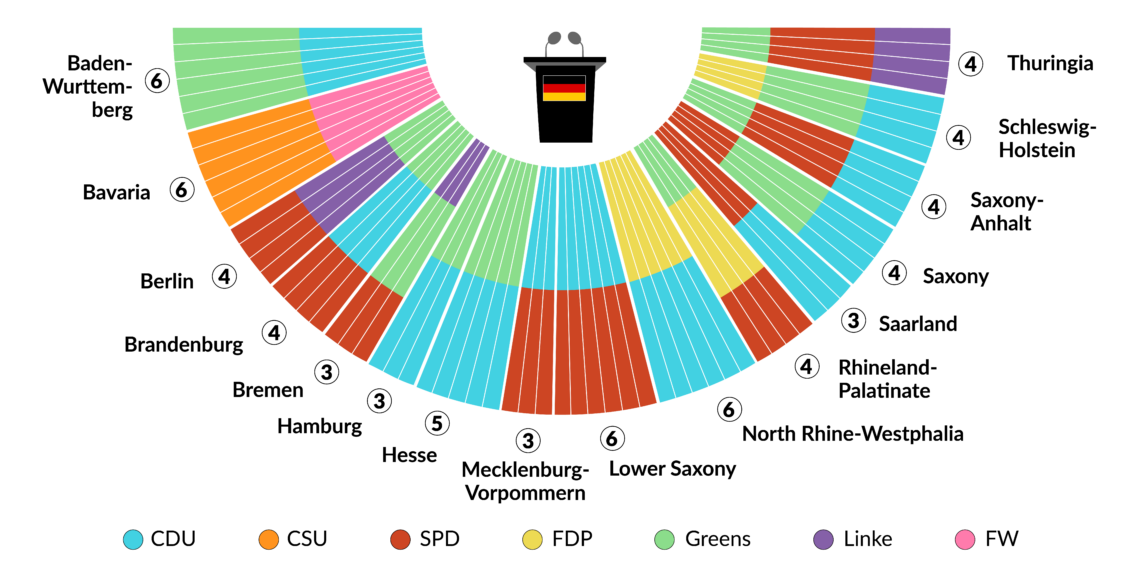

In short, German politics will become more complex and incoherent in 2020 and beyond. The current level of intricacy is already unprecedented. The illustration below shows the kaleidoscope of party coalitions in German states in its second chamber (Bundesrat). Seven parties are part of at least one of the 16 state governments of the federal republic. Both the conservative CDU (including her Bavarian sister, the CSU) and the SPD have proven they can form governments not only among themselves, but also with the Greens, the liberal FDP, and (in the case of the SPD) also with the far-left Linke. Only the far-right AfD – the largest opposition party in the federal parliament – is consistently denied power-sharing by all other parties.

Facts & figures

As a majority in the Bundesrat is required for many major parliamentary decisions, the federal government’s ability to engage in reforms is stunted. Not only would there have to be a consensus or compromise within a multiparty government coalition (supported by a majority in the first Chamber, the Bundestag), but also a majority in the State-Chamber representing governments from different coalitions.

Thus, leadership in Germany today does not merely require a government to have a great vision and the determination to get things done. It needs to be able to deal with a plethora of veto-players, to broker compromises, to engage in package deals that have to satisfy various local and ideological interests in the short run, often at the expense of long-term problem-solving. At the same time, this federalist system of checks and balances (including the strong role of the judicial system) has been introduced in the postwar German constitution of 1949 for good reasons. Leadership with unchecked power has done much more harm than good in German history. Still, the “joint decision trap,” which had already been identified by sociologists as early as the 1970s, has now become even more of a challenge.

Challenges in 2020

With a federal government plagued by increasing exhaustion and acrimony, a party system drifting toward fragmentation and a governance structure characterized by a procedural obstruction, Germany is not well prepared to meet pressing challenges.

After years of comparative economic stability and growth, especially in employment and exports, the German economy is facing a slowdown that could foreshadow severe structural changes in the industrial sector. To retain Germany’s competitive advantages in the global economy, both business leaders and legislators would need to adapt and innovate. The German government, however, seems unable or unwilling to go in this direction. On the contrary, it sticks to record-high tax and social security burdens, costly early retirement schemes, rent controls, minimum wages and ever more regulations. German energy and climate change strategies are textbook examples of expensive and ineffective policies.

Germany is not well prepared to meet pressing challenges.

Domestically, Chancellor Merkel has already become a lame duck. Especially in terms of economic policy, she has consistently tried to forestall her left-wing or green opponents by accepting large parts of their demands. This predilection had the combined effect of opening the door to a new right-wing party (the AfD) and forcing the SPD to drift further left. Thus far, the liberal FDP has not been able to fill the void by successfully pointing out the long-term consequences of these economic policies. Whereas Ms. Merkel may have given up on showing leadership in economic policy, she is most likely to use her last year or two in office to try and make a mark in European and geopolitical affairs. But her task has become more complicated than before.

After almost 15 years at the helm, she is respected as an experienced and trustworthy broker of international conflicts. However, with a limited residual term and a shaky domestic power base, Chancellor Merkel is unlikely to have much international leverage, let alone assume the role of “leader of the free world.”

Historically, postwar Germany supported the United States as leader of the free world, more often than not taking a free ride on American efforts. With the current U.S. president, however, the very meaning of a “free world” started to differ substantially in Berlin and Washington. Germany’s second most important international partner, France, is using this new environment to present itself as the geopolitical leader of a new, no longer transatlantic Europe. Hence, Ms. Merkel’s reliance on transatlantic relations and global multilateralism lost two key partners: President Emmanuel Macron and President Donald Trump.

Scenarios

Chancellor Merkel alone at home? 2020 and 2021 will see leadership contests taking place in Germany, with very uncertain outcomes. It is almost impossible to imagine any of the present party leaders as future heads of state. But then, the same was true of Ms. Merkel. In 2005, then-Chancellor Gerhard Schroder ridiculed her as being incapable of succeeding him. Many experts also found her leadership qualities lacking. Still, she is likely to remain the longest-serving leader of a major power in 2020.