Germany: The exhausted man of Europe?

Formerly Europe’s growth engine, the German economy is now lagging behind other eurozone countries. This poor performance is partly caused by the threats of U.S. tariffs and a disorderly Brexit. However, systemic problems are also contributing to the issue.

In a nutshell

- Germany’s industry sector is affecting economic performance

- China and Brexit are partially responsible, but there are domestic issues at stake too

- The German economy could recover, although only if Berlin capitalizes on opportunities

The German economy’s prolonged upswing is coming to an end. Leading economic institutes have slashed their growth forecasts for this year and next. The slowdown may be cyclical or due to external events beyond the control of German entrepreneurs and policymakers. But other possible causes reveal deeper structural problems in the German economy – issues that would require a serious change in economic policy.

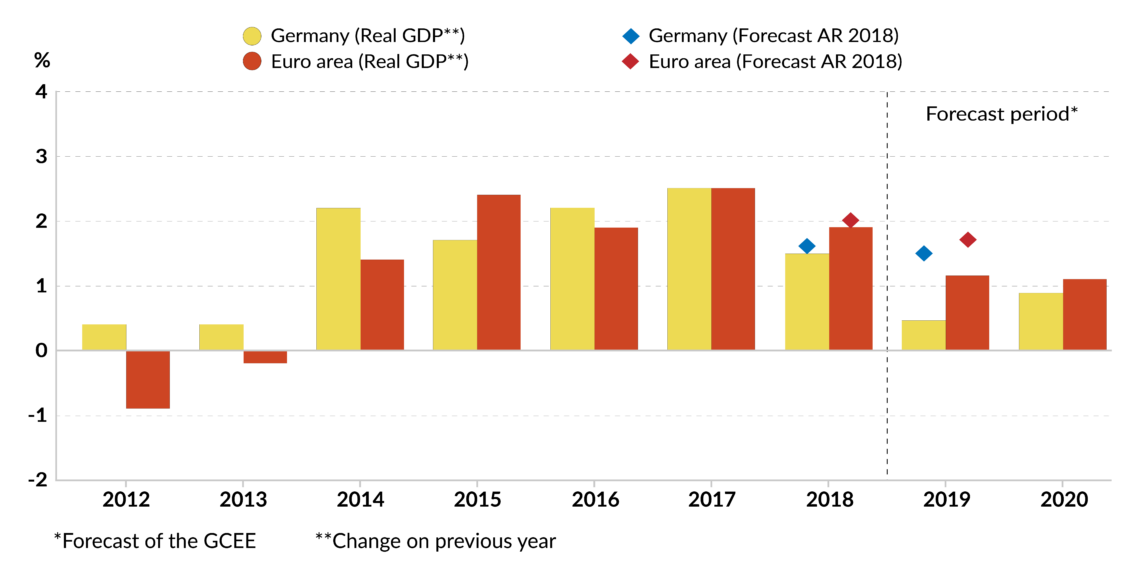

Let us first take stock. This November, the German Council of Economic Experts published its annual report on the state and development of the German economy. Much like other forecasts, it predicts that Germany’s real gross domestic product (GDP) will expand by a mere 0.5 percent this year. Growth in 2020 is forecast to be equally modest.

German demand for imports secures a total of almost 5 million jobs outside its borders.

Germany served as a growth engine in Europe from 2011 to 2017 by mostly preceding and underpinning the eurozone’s recovery. Now, it has one of the weakest growth performances in the EU; only Italy is doing worse. It could even become a drag on European growth (see graph above). Throughout the EU, German demand for imports secures a total of almost 5 million jobs outside its borders. Especially in neighboring countries, German demand for intermediate and capital goods accounts for roughly 7-8 percent of these countries’ GDP.

The main drag on Germany’s mid-term economic outlook is industry. Since October 2018, German industrial output has been continuously negative, with a decline of up to 4 percent over the summer of 2019. Germany has performed worse than France, Spain, Italy and even Greece in the first half of 2019.

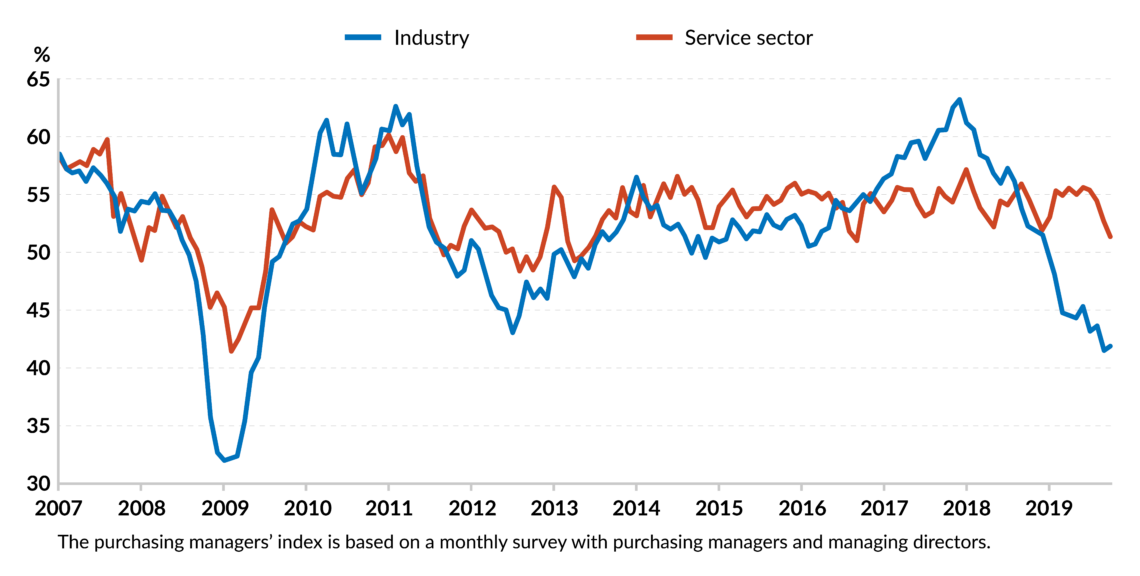

Future development does not look much rosier. The graph below illustrates the dichotomy between industry and the service sector in terms of purchasing plans (values below 50 indicate a contraction). Whereas the service sector remained positive, driven by domestic demand and a boost in construction, orders for manufactured goods have declined steeply. Recently, domestic orders have dropped more than foreign orders.

Facts & figures

Purchasing managers' index in Germany

Usual suspects

Germany is heavily dependent on exports, which account for 47 percent of its GDP. With global trade and industrial production in decline, this is the most obvious factor contributing to German industry’s chagrin. Since 2016, the usual suspects are United States President Donald Trump, China and Brexit. All three factors are sources of short-term risk, which explains cyclical nervousness and reluctance to invest. But they could also lead to long-term uncertainty and cause investors to hold their money out of the country.

Arguably, President Trump’s “America first” trade policies contributed to the precariousness underlying German industry leaders’ trade and expansion plans. So far, threats of tariffs and sanctions against the automotive industry have not been carried out. German car manufacturers have argued that most cars sold in the U.S. are also produced there, thus creating jobs. However, if Mr. Trump further threatens or even imposes tariffs on BMW or Daimler cars, German carmakers could be forced to “jump the tariff fence” and invest more heavily in the U.S. – or in South America, as long as trade relations remain unfettered.

Although Brexit has not yet been finalized, it is already affecting German business.

China and the United Kingdom also play a role in the decline in German industrial production. Both are major trading partners for Germany. The Chinese economy’s slowdown, along with its shift from manufacturing to services, reduced demand for German industrial products and machinery. This trend is likely to continue, not least due to demographic developments in China.

Although Brexit has not yet been finalized, it is already affecting German business. In the first half of 2019, German exporters to the UK lost revenue worth over 3.5 billion euros because of Brexit-related effects. The true extent of the damage to bilateral commerce will likely become visible next year, as many firms have just replenished their stocks in Great Britain to prevent supply chain disruptions in the coming months. According to cautious estimates, Germany’s 2020 GDP would be lower by half a percentage point under a disorderly Brexit than under an orderly one.

Problems made in Germany

German industry’s problems cannot be wholly blamed on cyclical or foreign factors. Much of the malaise is made in Germany. Indeed, the very trademark “made in Germany” itself has suffered.

For the last 20 years, the Edelman Trust Barometer has shown that people in other developed economies had the highest trust in German companies, products and management. This year, trust has fallen to only 44 percent, a year-on-year drop of 15 percentage points. This may reflect issues encountered by Bayer-Monsanto, Deutsche Bank or several German car companies.

The German automobile sector is not only suffering from a loss of reputation, but also a lack of vision.

The German automobile sector is not only suffering from a loss of reputation, but also a lack of vision. Experts predict global car demand to stagnate. Moreover, Germany’s competitors abroad have long been more reactive to mega trends such as e-mobility, digitalization or autonomous driving. German carmakers no longer seem to act as technology leaders. Recently, Volkswagen announced it would spend 60 billion euros on electric vehicles, automated driving and other technology over a period of five years. But it is catching up, even in the domestic market. In terms of fully electric vehicles, so far this year Tesla is the bestseller in Germany, followed by Renault. German brands BMW and Volkswagen are lagging behind at home.

In almost all sectors of German industry, productivity growth has been weak for several years. This can partly be explained by the aging population and workforce and slow adaptation to new technologies. The ability to innovate is also often discouraged by hefty regulations and widespread skepticism toward any technology branded “fossil,” “atomic,” “genetic,” “digital” or “artificial” instead of “green.” This popular political attitude may also help explain why more businesses have been closed than founded in all sectors.

Moreover, venture capital investment still plays only a minor role in Germany. The World Bank and International Finance Corporation (IFC) rank Germany 125th out of 190 for ease of starting a business, largely because of the complex procedures companies are required to navigate.

Minister Altmaier’s plan

Earlier this year, Germany’s Minister for Economic Affairs and Energy Peter Altmaier laid out a plan entitled “National Industrial Strategy 2030.” Instead of addressing the above-mentioned regulatory and mental barriers to innovation, he wants his administration to take stakes in strategic industries to fend off takeovers by foreign companies, especially Chinese ones. Very much in line with French demands on the European stage, Mr. Altmaier also calls for a redrafting of EU antitrust regulations and the creation of heavyweight business “European champions” to rival those in the U.S. and China.

“Industrial policy strategies are experiencing a renaissance in many parts of the world,” the paper argues. “There is hardly a successful country that relies exclusively … on market forces to cope with its tasks.”

Minister Altmaier may have a point here, but his approach was met with a lack of enthusiasm from German industry and fierce criticism from German business associations. The old idea of picking the winners and protecting the losers with state subsidies, encouraged mergers and government stake-holdings, they argue, can hardly be successful in maintaining the competitiveness of the German or European industry.

Considering the foreign, domestic, economic and political challenges to the long-term development of the German economy – especially its backbone, the export-oriented industry sector – both a pessimistic and optimistic scenario can be drawn.

Pessimistic scenario

Things could get much worse for German industry, especially if several of the following developments occur:

- Current trade disputes further escalate, possibly affecting German exports directly by way of Chinese or American tariffs on EU cars and other industrial products.

- A chaotic Brexit leads to no trade agreement between the UK and the EU by the end of 2020. The transition period is not prolonged and the UK trades with Europe on World Trade Organization terms.

- The lack of skilled labor becomes a barrier to structural change. Germany turns into an aging society with an education system that does not provide skills needed by the market. Domestic labor supply does not match industry demands. German bureaucracy, taxes, social security contributions, and protectionist laws concerning services discourage talent from abroad.

Germany is not going to be the ‘sick man of Europe’ but it is also not fit.

- Political instability in Germany takes its toll. The new and more radical left-wing leadership of the Social Democrats takes the party out of the “grand coalition,” prompting early elections next year that may further damage centrist parties. In the worst case, this leads to Weimar-style ungovernability, but it is more likely to create delicate three-party coalitions either on the far left (led by the Green party) or around the center (led by the Christian Democrats).

- Pushed by populist demands, a new German government further yields to economic irrationality, especially in energy and climate policy, after weaning the country off both fossil and nuclear energy. German energy stays among the most expensive in the world, raising costs for industry. The welfare state expands through more unsustainable pensions, stark increases to the legal minimum wage and social security payments, further increasing labor costs. Entrepreneurial activity becomes overregulated or nationalized, raising compliance costs and discouraging innovation.

- As a result, German business keeps investing, but mostly abroad where skilled labor is less scarce, productivity gains are more likely and labor costs and the regulatory climate are more attractive.

Optimistic scenario

Things are not as bad as the doomsday scenario above suggests and could even improve, if the following opportunities are seized.

- The dynamics of globalization may have paused, but its potential is far from exhausted. The German government and businesses are eyeing the African continent for opportunities for trade and direct investment. Even the EU single market is far from complete. Especially in the realm of services, many gains from trade can still be reaped. Also, the new trade agreements between the EU and Canada, South Korea and Japan offer opportunities for German industry – which will keep taking advantage of a weak euro due to the loose monetary policy of the European Central Bank (ECB).

- Germany retains key factors for global competitiveness. A recent study by the Institute of the German Economy (IW) compares the competitiveness of Germany as a location for industrial production to that of 44 of its major competitors. Based on 60 indicators, Germany came out third, after Switzerland and the U.S. Its major strengths are infrastructure (logistics), knowledge foundations (students focusing on math, science and technology, patents and research and development) and legal framework. Its downsides are high labor and energy costs – factors that are not beyond domestic control.

- Germany could become a key location for foreign direct investment on its own strategic domestic turf: Tesla CEO Elon Musk recently announced that the American automotive company will invest four billion euros to build its first European “gigafactory” in Brandenburg. Since this could create up to 10,000 jobs, the news was most welcome. It shows that Germany still has comparative advantages.

Germany retains key factors for global competitiveness.

- Germany’s industrial backbone will remain in the “Mittelstand,” meaning highly flexible and innovative small and medium-sized enterprises, often still family-owned. These hidden champions may not make it on the list of European champions protected and subsidized by governments in Berlin or Paris, but they are often world market leaders in highly sophisticated products driven by digitalization. They are also more likely to be ready for developments in artificial intelligence while remaining true to quality.

- Germany is well prepared for an economic slowdown. The German government has recorded budget surpluses for the last five years and is expected to add another 50 billion euro surplus this year. According to government spending plans and tax-base forecasts, the surpluses could dissipate by 2021. But compared to other countries in Europe (Italy, France, the UK) or beyond (the U.S., China, Japan), Germany is much more likely to avoid an imminent spiral of economic and fiscal decline. Even if industry keeps cutting jobs, service providers and the construction sector are hiring and may keep doing so. Unemployment rates will most likely stay around 5 percent.

- Germany’s political landscape may reposition itself toward the center. The recent rise of populist parties both on the right and left and especially in local or European elections may have been a “luxury problem.” After years of comparable prosperity, voters’ attention drifted to issues of identity, ideology and envy (distribution). Voicing discontent with political and business elites is common in times of economic stability. With a likely slowdown or even mild recession, one can expect German voters to focus on questions of economic competence and institutional trust. Radical demands, like nationalization from the left, economic nationalism from the right and “degrowth” from the greens, are less likely to garner support in times of economic challenges.

Scenarios

The most likely outcome is a blend of both scenarios. The latter are extreme depictions of current possibilities. A serious reemergence of the euro crisis would of course not only destabilize banks in Italy and Europe. It would also hurt Germany’s economy as a whole, including its industry sector and not least its fiscal budget. Germany is not going to be the “sick man of Europe” (the European sick bay has sicker clients) but it is also not fit.

The country is more likely to become the “exhausted man of Europe,” still somehow able to stand with the assistance of a wheeled walker provided by the ECB. This would mean a Germany with little energy left, but with a chance to undergo the revitalization it needs.