2019 Global Outlook: Another year near zero

It has been a decade since global interest rates reached the zero lower bound, where monetary policymakers lose their ability to stimulate the economy using conventional policy tools. Among the largest central banks, only the Federal Reserve in the United States has set its benchmark above 2 percent. Will this anomaly end in 2019?

In a nutshell

- Keeping interest rates near zero has introduced anomalies into the global economy

- Malinvestment and structural imbalances have built up, increasing vulnerabilities

- Zero rates also leave policymakers with fewer tools to respond to the next downturn

“I once went on a blind date with a gal. It was like a bond with zero-percent yield.” “Why do you say that?” “Because she had no interest.” This little vignette introduces the musical satirist Merle Hazard’s 2016 song “How long (will interest rates stay low)?” Just like a cagey policymaker, the song fails to answer the question in its title.

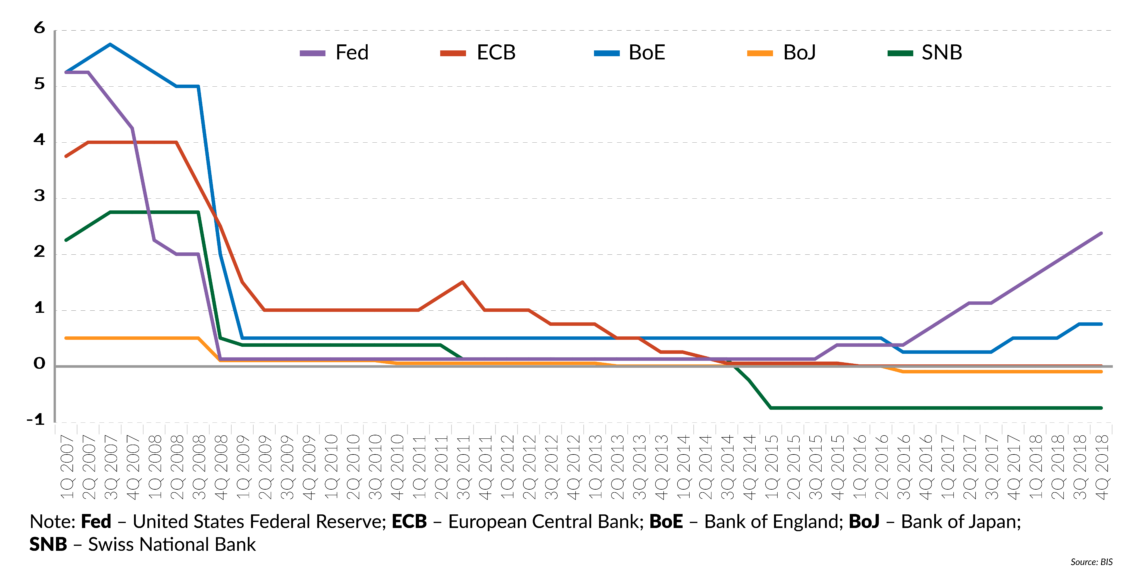

It has been a decade since global interest rates reached the zero lower bound, where central banks lose their ability to stimulate the economy using conventional policy tools. Borrowing costs have mostly stayed there since. The European Central Bank, the Bank of England, Denmark’s Nationalbank and the Bank of Israel, among others, have kept their reference rates at or around zero. The Bank of Japan, the Swiss National Bank and Sweden’s Riksbank are still in negative territory. Among the largest global central banks, only the United States Federal Reserve has set its benchmark above 2 percent. Will this anomaly end in 2019?

According to one theory, central bank interest rates should mirror the amount of risk to which a currency or country is exposed. At the same time, they should reflect and encourage the productivity of capital. Another, different theory holds that the neutral (or natural) rate of interest is one that allows real gross domestic product – i.e. output adjusted for inflation – to grow at its trend rate, with stable inflation.

In either conception, keeping central bank interest rates close to the zero lower bound is anomalous in at least three ways. As we will discuss below, each anomaly is dangerous and costly to correct.

Misallocated investment

The first anomaly is malinvestment. It results from the inability of investors to foresee correctly, at the time of investment, the future pattern of consumer demand or the future availability of more efficient ways to satisfy this demand. Poorly allocated investment becomes even more likely if the information available to markets (especially prices) is systematically distorted.

That is precisely what happens when interest rates reach the zero lower bound, distorting vital information about risk and the price of money. Zero rates send a falsely reassuring signal about future investment risks or indicate that future prices (and therefore inflation) will be low. Both messages incentivize investors to plan for long-term returns on capital and lower depreciation. They also create disincentives to the productivity of capital.

When reality snaps back, as it usually does, investors realize that their decisions were systematically wrong.

When reality snaps back, as it usually does, investors realize that their decisions were systematically wrong. They discover that the investment risk they calculated for did not fully reflect the real risks. In this case, investors can pass the higher risk premium along the supply chain, making products less attractive. If they lack market power, they will have to pay the premium themselves, at the cost of lower profits. If liquidity is short, investors may also abandon investment products unfinished.

Alternatively, investors can be confronted with inflation rates higher than their original calculations. For example, if zero interest rates prompted investors to allow for zero annual depreciation, inflation of even 1 percent would force them to incur losses. Here, too, investors often cut their losses and liquidate investments, even unfinished ones. Otherwise, high inflation might render them insolvent.

This malinvestment could make itself felt in 2019. As pension funds explore the fringes of their risk tolerance, scouring ever-riskier asset classes for a performance boost, the many vulnerabilities of a financial system with near-zero interest rates could become apparent. Most exposed are asset classes that have attracted investment inflows without appropriate returns – including real estate, sovereign and private debt, and trendy industries such as social media and clean technology. A potential crash could engulf the equity and debt markets, along with companies and individual households.

Facts & figures

Policy rates of major global central banks

(2007-2018)

Structural imbalances

The second anomaly of zero-rate policies are the structural imbalances to which they lead. While malinvestment – for all its spillover effects – is the individual investor’s problem, structural imbalances have a systematic effect on potentially every economic agent. In the long run – and 10 years certainly qualifies on that score – the accumulated weight of imbalances caused by interest rates around zero can warp the entire structure of an economy.

The most important imbalance is growing income disparity and reduced purchasing power. A zero interest-rate policy represents a transfer of wealth from savers to banks, debtors and leveraged investors. With low interest rates, investment income cannot keep up with inflation and taxes. This erodes purchasing power. The loss of compounding factors diminishes savings, especially in pension plans. Some individuals then become more reliant on the state and social services to bridge the income gap created by lost purchasing power and savings.

Another structural imbalance is loss of productivity. In a zero-interest environment, it is easy for most investments to outperform. But with no pressure on capital markets to improve productivity, there is no pressure on labor to be more productive as well. As a result, productivity gains are smaller or even stagnant. This has important implications for the creation and distribution of wealth. Systematically lower productivity does not generate new income but only rearranges it.

The problem with structural imbalances is that they are hard to correct. The damage they inflict becomes embodied in the economy. Income and purchasing power, once distributed, cannot be called back; their loss is irrevocable. The cumulative impact of these flows, over a period of years, becomes a visible tax on the economy. In the best case, the damage takes the form of individual losses and corporate write-offs. At worst, it can lead to mass insolvency and social unrest.

Policy bankruptcy

Another important anomaly of zero interest rates is that they render some monetary policies ineffective. Usually, central banks lower interest rates in times of recession and depression, increasing the quantity of money in an economy. These measures make savings less attractive and boost the expansion of money and credit, which eventually feeds through to investment and consumption.

While these policies belong in the countercyclical toolbox, interest rates have stayed near zero for this entire recovery cycle. Entering the eighth year of economic recovery with the same monetary prescription, central banks have nothing in reserve for the next downturn. Their toolbox is empty.

If enough investors believe they are being manipulated, monetary policy could lose all credibility and effectiveness.

The fact is, zero interest rates no longer pack the punch they used to. Even if central banks were to lower their reference rates into negative territory, that does not match the impact of slashing borrowing costs from 4 or 5 percent to zero. Perhaps the lowest they could go is to between zero and -1 percent, which is meager by comparison. Going lower is not feasible, because it would risk a withdrawal from conventional banking into shadow banking and the use of barter and alternative currencies by economic agents.

One must also reckon with a cultural feedback loop. If a large enough group of agents realize that they are being manipulated by the monetary authorities and lose faith in banking, then monetary policy itself could lose all credibility and effectiveness.

Cautious pessimism

There seems to be a general reluctance to raise interest rates. Even the Fed, the only major central bank to do so, is slowing down. Japan and Switzerland, where borrowing costs have long been negative, have not hinted at reversing their policies. The ECB and the Bank of England decided on modest hikes and then fell silent.

It is highly unlikely that borrowing costs will rise in 2019. The more volatility we see in the financial markets, the greater caution will be exercised by central banks. Most countries and currency zones are ill-prepared to deal with higher interest rates, because that would mean greater costs in servicing excessive public debts. Policymakers also know that the equity basis of most corporations is thin, since share-buyback programs encouraged by near-zero interest rates can leave companies dependent on external financing if a crisis hits.

But a no-hike scenario only deepens the anomalies discussed above. All that remains is hope, as in Merle Hazard’s song:

Capital’s abundant, money’s not in short supply

China holds our Treasury bonds, although I wonder why

Start-ups happen in the cloud, few people are employed

If something could push rates back up, I’d be overjoyed.