Greenland moves slowly toward independence

Greenland has passed a draft constitution, raising the possibility of independence from Denmark and concerns over its strategic significance.

In a nutshell

- Greenland’s draft constitution is a move closer to independence from Denmark

- U.S. bases on the island raise questions about future sovereignty

- Chinese investment potential and strategic location make Greenland’s independence significant

In early June, Greenland unveiled a draft constitution that the locals see as a key step toward independence from Denmark. A decade ago, this would not have attracted much attention; today’s confrontation between Russia and the United States makes the strategically located island vastly more important. But while Greenland’s direction of travel is clear, it is not at all certain when – or even whether – it will ultimately reach the goal of full sovereignty.

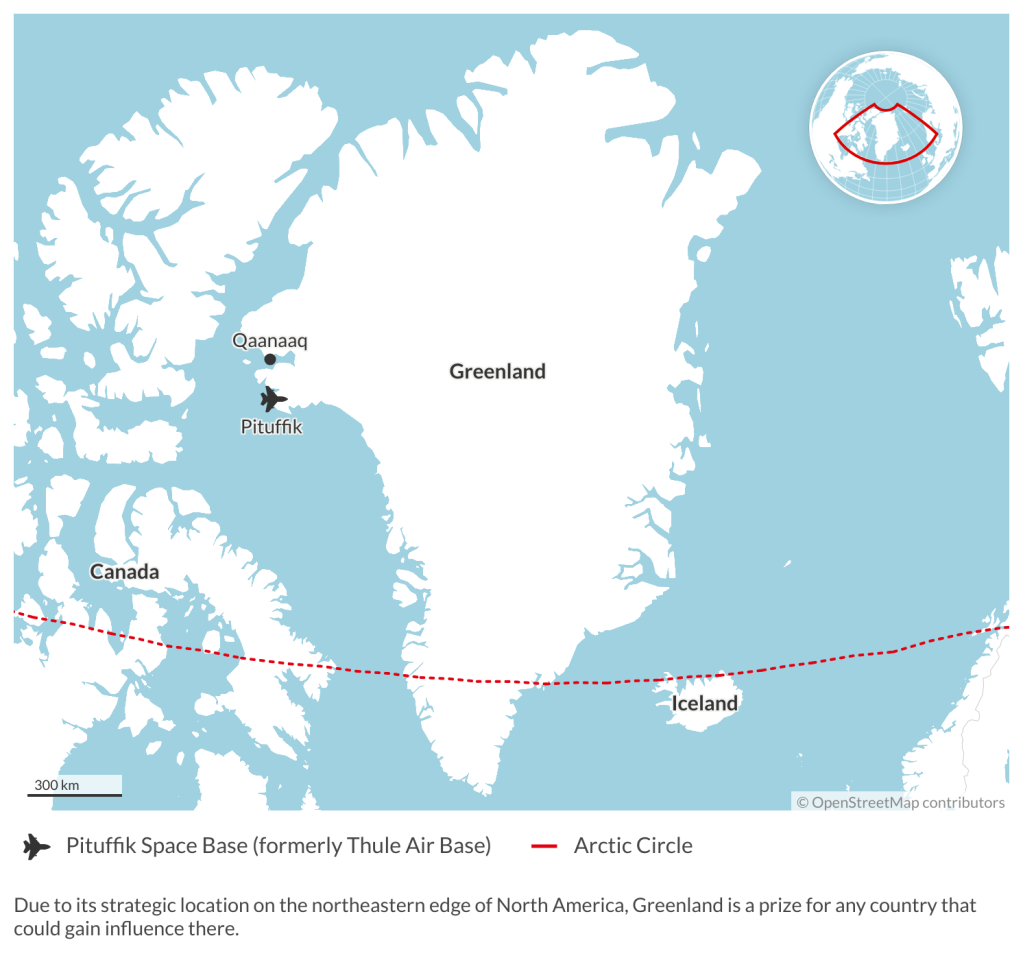

Since the early 1950s, the U.S. Air Force has operated a base at Thule, on the northwestern edge of the island. Located 1,200 kilometers north of the Arctic Circle, it is the northernmost base of the U.S. armed forces. Originally built for the Strategic Air Command’s legendary B-52 bombers, over the years it has developed into a key piece of the early warning missile defense system. In 2020, Thule was integrated into the U.S. Space Force.

As a founding member of NATO, Denmark has been accommodating in granting rights for U.S. military installations on Greenland, in some cases even agreeing to the forced removal of the local population. The only demand from the Danish side has been that its flag must fly alongside the Stars and Stripes.

An early warning that continued Danish control over Greenland may not be ironclad came in 2019, when U.S. President Donald Trump offered to simply purchase the island. After all, America’s 19th-century acquisition of Alaska from Russia has turned out to be a pretty good deal. As it happened, the bid for Greenland was turned down, and in no uncertain terms.

The prime minister of Greenland at the time, Kim Kielsen, made it clear that his island was not for sale, adding that even if it were, the offer must be aimed at Greenland and not at Denmark. From Copenhagen, Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen declared the same, noting that “Greenland is not Danish. Greenland is Greenlandic.”

As a self-proclaimed master dealmaker, President Trump may have felt he was the man to gain full U.S. control over an important strategic asset. Or perhaps it was just another whimsical play for media attention. Whatever the reason, the incident shone a light on the relationship between Denmark and Greenland.

Strategic location

If Greenlanders do manage to secure independence, they will be in control of some highly valuable real estate. With a mere 57,000 inhabitants, and with 80 percent of its land mass covered by ice, the island’s economic importance may seem negligible. But its strategic location tells a different story.

Facts & figures

An independent Greenland would be a tempting target for Chinese investment. As an aspiring Arctic player, Beijing may be expected to seek deals on matters ranging from renewable energy to ground stations for satellite communications, not to mention access to harbors and airfields. NATO will not be able to hinder Chinese ambitions to incorporate such investments into its overall military planning.

While this scenario clearly is not in the cards any time soon, it does bring home that the question of independence reaches beyond the moral issue of rights for a relatively small group of people.

It is also a big deal for the government in Copenhagen. With Greenland, Denmark is one of the world’s larger countries by area, and it has a guaranteed seat at the table in Arctic affairs. Without Greenland, Denmark would be reduced to a smallish country on the northern edge of the European continent. It would still be in control of the Faroe Islands, but that would give it a much weaker voice in the Arctic.

Denmark’s claim

A key question here is whether Denmark really does have a legitimate claim to Greenland. It may be tempting to respond by invoking the saga of Viking expansion, of the Norsemen in their longboats, who sailed across the high seas making conquests. But the case of Greenland is a poor fit.

It is true that Vikings sailing from what is today Denmark left a major imprint on territories subjected to their violent raids, not least in Britain; in what is today France, their appearance caused monks to say the legendary prayer “From the wrath of the Norsemen deliver us, O Lord” (A furore Normannorum libera nos, Domine). The Viking chieftain Rollo’s descendants include both William the Conqueror, who defeated the Anglo-Saxons at Hastings in 1066, and the rulers of southern Italy who formed a successful Norman Kingdom in Sicily.

More on the Arctic and the Nordics

NATO’s Nordic bloc: Big promise, lurking problems

The Arctic in Russia’s crosshairs

The saga of the Vikings who sailed from today’s Norway is fundamentally different. They did not leave any imprint even remotely comparable to the Norman Conquest. In 982 a Viking named Erik Thorvaldsson, also known as Erik the Red, set sail from Iceland toward the west, where he discovered what he dubbed Green Land, hoping that word would spread and attract more settlers. (It was his son, Leif, who proceeded to discover North America, four centuries before Columbus was born.) But by the mid-15th century, the Norse settlers had disappeared from Greenland, for reasons unknown.

The rediscovery of the island may be dated to the mid-18th century when a missionary from Norway, then part of Denmark, traveled west in search of descendants of the Norsemen. He found none. The local population was made up of Inuit settlers, recognized today as the aboriginal population.

That rediscovery triggered immigration from Denmark that resulted in it being claimed as a Danish colony in 1775. That claim would not be recognized by the U.S. until 1917, as part of a deal to purchase the Danish West Indies, later known as the U.S. Virgin Islands. Recognition by other countries was even slower, coming only in the 1930s. In the meantime, Danish settlers had established themselves as colonial rulers, building a track record of treating members of the aboriginal population as second-class citizens.

Political transformation

During the decolonization process after World War II, Greenland’s formal status was slowly transformed. In 1953 it was changed from colony to county. In 1979 the island was granted home rule, including an elected parliament, and following a referendum in 2009, it was granted self-government, with exceptions for core areas like foreign and security policy, monetary policy and the judiciary. Today’s draft constitution, in the works for six years, has boosted expectations for full independence to follow. For some, a formal divorce cannot come soon enough.

Greenland’s struggle for independence may be usefully viewed as one of the final acts in the drama of dismantling European colonialism. As in other cases of liberation, dark stories of past maltreatment are coming to the fore. The grievances of the Inuit in Denmark have much in common with similar complaints from their brethren in Canada. The difference is that Greenland is an island, making independence more straightforward.

The removals for U.S. bases have fueled much anti-American sentiment over the years. In one case, 130 people were evicted from an air-defense site and moved to a newly constructed village known as Qaanaaq, or “New Thule.” In 2003, the Danish Supreme Court ordered the Danish government to pay compensation, both to the Thule tribe and to individual members who had been forced to relocate.

A particularly egregious case of social experimentation with the aboriginal population came in the early 1950s, when 22 Inuit children were taken from their homes and transported to Denmark, to be raised as Danes. The ambition was that they would form a new intelligentsia that would help lift Greenland out of poverty and backwardness. After a year and a half, they were returned to Greenland, where they were housed in a Red Cross facility and prevented from speaking their native language.

Upon reaching adulthood, many returned to Denmark, where some developed mental health issues and succumbed to substance abuse. In December 2020, the Danish government issued a written apology but refused monetary compensation. Faced with a lawsuit from six survivors, this year the government agreed to settle and pay each survivor about $37,000 in compensation.

The case for independence is further boosted by the makeup of the population: 88 percent are either direct descendants of Inuit or have mixed lineage. Under self-rule, they have two representatives in the Folketing, the Danish parliament. In May, one of them, Aki-Matilda Hoegh-Dam, caused outrage by refusing to speak Danish during a session. She reported being subjected to abuse that she claimed was representative of how Greenlanders are still considered second-class citizens.

Scenarios

Continued movement toward independence is clearly the most likely scenario, though it remains unclear how far Greenland will travel down this path, and how fast. Despite Copenhagen’s reluctance to let Greenland go, rising expectations make it almost impossible to preserve the status quo, so the current constitutional process is bound to result in a considerable shift of power.

But it is not clear that this will entail full independence. It would be a heavy lift for Greenland to assume full responsibility for the policy areas still handled by Copenhagen, while giving up an annual subsidy of more than $500 million.

The most likely outcome is a protracted gray zone of continued negotiations, accompanied by rising frustration for Greenlanders and rising worry from the outside world. Western countries are concerned that independence would provide openings for both Russia and China to exploit the island’s mineral wealth. And there is a specific concern in the U.S. that latent anti-American feelings will jeopardize Greenland’s crucial role in NATO.

It is symptomatic that in April this year the Thule Air Base was renamed the Pituffik Space Base. In literal translation, “Pituffik” means “the place the dogs are tied.” It refers to a cluster of huts on the wide plain that locals had to vacate to make room for the base, and it brings back memories. Although the war in Ukraine has put a damper on anti-American sentiments, memories of past maltreatment will linger, and may still result in protests.

Still, the main concern is that increased power for the Greenlanders over the judiciary and economic policy will provide tempting openings for Chinese direct investment, perhaps even including an invitation to join the Belt and Road Initiative, like the one issued to Iceland in 2018. This would turn the world’s largest island into yet another arena for deteriorating U.S.-China relations. Although the probability remains low, the outcome would represent a major shift.