Labor markets, education and growth

Taxation and overregulation have sapped Western countries’ entrepreneurial energies. But the worst part of the low-growth problem is workforce education.

In a nutshell

- Economic growth, not fiscally repressive policies, solves economic problems

- Healthy labor markets are conducive to strong, sustainable growth

- Too many young people learn too little and stay in school for too long

Policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic agree that inflation and growth are much better ways of sustaining public indebtedness than fiscal restraints and monetary rigors. This does not mean, of course, that inflation was the goal when central bankers started engaging in expansionary monetary policy.

There is no doubt that inflation helps borrowers and that governments are avid borrowers, but growth is also essential.

Inflation does not hit all people to the same extent; instead, it involves the significant redistribution of income and strikes the poor particularly hard. This phenomenon creates winners and losers and is tolerable only if growth is satisfactory and the benefits it generates at least partially compensate the losers.

The labor market’s relevance

Let us focus on growth, where the number of individuals engaged in productive activities and their productivity play critical roles. It explains why the features of labor markets are relevant and why one should rejoice when unemployment declines and employment expands. The business world appears to be doing the opposite and celebrates when the labor market eases – i.e., the unemployment rate goes up; that attitude applies particularly to the United States.

Distorting the labor market by paying people not to work is hardly a recipe for growth.

In fact, it is believed that high unemployment encourages central bankers to ease monetary policy and make life easier for heavily indebted companies. This attitude is shortsighted. In Europe, policymakers are less interested in what happens to the labor market: unemployment is relatively high, but generous European welfare systems are a robust safety net against tensions. That is why labor markets hardly make headlines here. This attitude is also questionable since distorting the labor market by paying people not to work is hardly a recipe for growth.

Europe vs. the U.S.

As mentioned above, the number of workers and their productivity matter. The “numbers” refer to the share of the population engaged in productive activities, while “productivity” relates to the results of their work efforts. Within this framework, the U.S. and Europe tell us different stories. Let us consider the two economies and emphasize three critical issues: participation, skills and education.

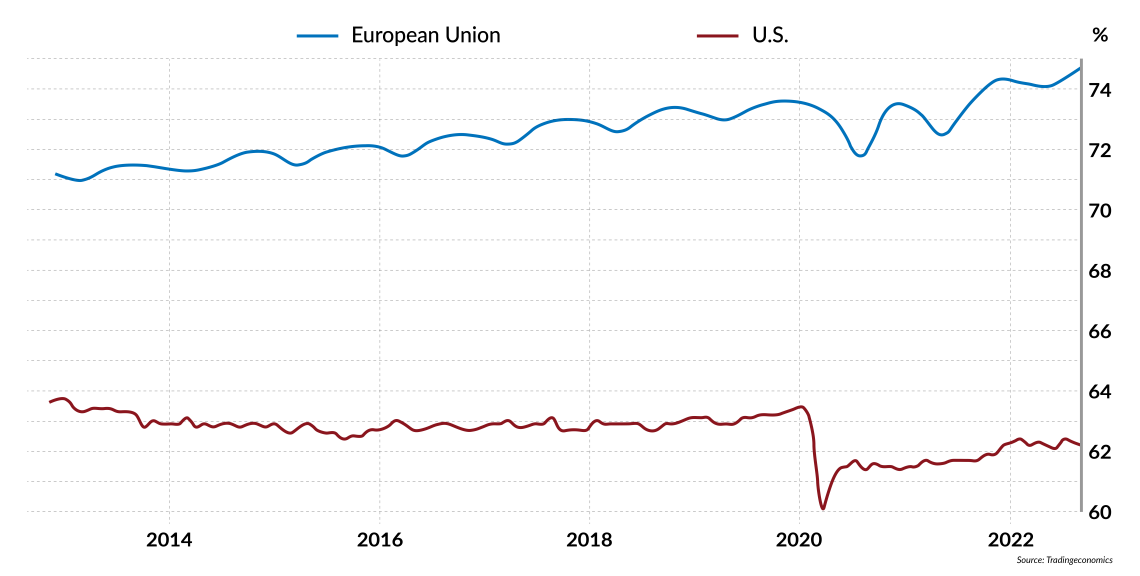

Regarding the “numbers,” the U.S. seems to be in reasonably good shape. Unemployment is low (the official unemployment rate is 3.5 percent, and the long-term unemployment rate is below 1 percent), and youth unemployment is tolerable (about 8 percent). Moreover, about 81 percent of the employed are full-time. However, there are also some not-so-bright spots. These are mainly the extended stay in the educational system and the labor force participation rate – how many working-age individuals have a job or are looking for a job – which is just 62 percent in the U.S., some 5 percent lower than 20 years ago.

Low productivity puts Western economies at a crossroads

At the same time, job vacancies are high – more than twice the average for the 2010-2020 period. That means that potential employers cannot find suitable candidates. The U.S. labor market shows that all those willing to work have employment, but many potential workers are not interested in entering the labor market: some prefer to stay at school or home, and others do not even try, possibly due to their lack of marketable skills and the low wages they would be offered.

Enter: skills

Productivity comes from innovation and skills. Innovation depends on entrepreneurship, which is influenced by the institutions (taxation, regulation, quality of the judicial system). What about skills? Are American workers able to take advantage of the opportunities that technologies offer them? Do the long years spent at school produce satisfactory skills and justify the delayed entrance into the labor market? During the post-World War II period in the U.S., the yearly average rise in productivity (output per the hours worked) was 2.5 percent until the early 1980s and 1.6 percent afterward.

More than 20 percent of students leave the U.S. educational system with no or minimum learning outcomes.

Even if we take back-of-the-envelope assessments with a grain of salt, the impression remains that the quality of the labor force (skills plus working effort) has not increased much. It also seems that productivity growth has been achieved thanks to user-friendly advanced technologies and larger quantities of fixed capital (machinery) rather than because of more sophisticated human resources.

In other words, skills have not improved significantly, and production has increased thanks to more machinery. Indeed, average skills are low: for example, more than 20 percent of students leave the U.S. educational system with no or minimum learning outcomes. The fact that the U.S. data is similar to those of other advanced countries (and generally below those countries regarding mathematics) is far from reassuring.

Europe’s weak spot

The European situation presents some distinctions. Here are the key figures: the European Union labor force participation rate is 74.6 percent, higher than in the U.S. and rising (it stood at about 68 percent two decades ago), while the rate of unemployment is 6 percent, which is low by Europe’s standards. The presence of part-time workers (about 18 percent of those registered as employed) is like that of the U.S.

Facts & figures

EU and U.S. labor force participation rates

Even if youth unemployment has declined in Europe from 25 percent (2012), it is still relatively high (about 14 percent today) and is unlikely to drop further soon. The European disease appears to be youth unemployment, which probably explains much of the higher overall unemployment rate compared to the U.S.

Education is also a problem. According to the European Skills Index, in 2022, the educational system in the median EU country develops only 53 percent of its students’ potential – leaving a gap of 47 percent. Among large countries, such a gap is “limited” to 41 percent in Germany but soars to about 60 percent in Spain, France and Italy. From a historical viewpoint, this data may help explain the meager growth in productivity, which rose at an average yearly rate of less than 0.8 percent during the 1995-2022 period and at less than 0.6 percent clip during the past decade.

There are no education reform projects in sight, and it takes at least half a generation before the launched reforms start bringing results.

The EU employed seem to be a much larger fraction of the working-age population than their American counterparts. However, too many young people in Europe struggle to find a job – or, perhaps, are not overly eager to find one. The educational question plays a key role: too many young people learn too little at school, and their poor performance leads to stagnant productivity and low growth.

Generally, growth rests on three primary pillars: entrepreneurship and innovation, machinery, and people. In the West, taxation and regulation have sapped productive entrepreneurial energies. Gross fixed capital formation (machinery) has suffered, especially in the EU, where the yearly average gross domestic product growth rate over the past 25 years has been a mere 1.7 percent. In the U.S. it reached 3.5 percent.

Scenarios

The worst part of the problem is people and their education. In the OECD area, over 20 percent of those aged 16-25 lack elementary language or math skills, or both. This percentage is about 20 percent in Germany, while it reaches higher than 30 percent in the U.S. France and Italy are above 30 percent and 35 percent respectively.

There are no reform projects in sight, and it takes at least half a generation before the launched reforms start bringing results. Nowadays, a significant share of the youth does nothing (the OECD average is about 15 percent), while many young people are kept at school for too long while learning relatively little. That is happening on both sides of the Atlantic. As a result, performance at the workplace is unsatisfactory.

In the past, massive hiring in public administration could hide the problem and ensure that low-skilled workers could find a job. “Value-added accounting” (the difference between revenues and the cost of goods and services purchased by a business) in the public sector would feed the illusion that production grew at favorable rates.

That will no longer be the case in future years, especially if policymakers respond to the challenge by lengthening the educational career, rewarding “social abilities” rather than studying, and increasing public expenditure to recruit more significant numbers of inadequately trained teachers.

Facts & figures

Faux growth

Added value in the public sector is, in fact, considered equal to the salary of the employees, as the price of what the public sector sells – e.g., public health and public education – is well below costs and frequently zero. Thus, if the government wants to raise the value of what it produces, it just needs to hire more civil servants and/or raise their salaries.