Increasing oil competition in Asia

The first supertanker bearing U.S. crude oil to Asia after a 40-year export embargo was liftd left the Gulf Coast of Louisiana in February 2018. The event was hailed as the start of a new oil trading era, and possibly the start of a war for market share in Asia between U.S. shale producers and conventional exporters from the Middle East.

In a nutshell

- The U.S. is becoming a major oil exporter, and Asia is the fastest-growing market

- However, Middle Eastern producers enjoy important cost advantages in selling to Asia

- U.S. tight oil is a bigger threat to West African or Libyan producers

When the first supertanker laden with crude oil left the Gulf Coast of the United States for Asia on February 18, 2018, it caused a media frenzy. Hailed as the beginning of a new oil trading era, the 2 million-barrel cargo set reporters to speculating that it would ignite a war for Asian market share between shale producers and conventional exporters, especially from the Middle East.

Since the lifting of a 40-year export ban[1] in December 2015, thanks to the shale boom, U.S. oil has been sold to 33 countries. Asia is taking an increasing share of those sales. This trend is likely to continue, but it does not mean game over for Middle Eastern producers. In fact, of all the oil exporters to Asia, they should probably be the least concerned.

Before plunging into analysis, it is important to highlight one essential fact that seems to get overlooked in such discussions: oil is a fungible commodity traded in a global market. Looking at regional market shares is not enough. Saudi Arabia, for instance, may send more oil to the U.S., allowing U.S. producers to divert some of their output to Asia. In our case, looking at the Asian market alone gives an incomplete picture of global oil market dynamics.

Facts & figures

Oil export facts

- On December 18, 2015, the U.S. enacted legislation authorizing the export of domestically produced crude oil without a license. Prior to that, exports were restricted to: (1) crude oil pumped from selected fields in Alaska’s Cook Inlet Basin; (2) oil from the Alaskan North Slope; (3) certain domestically produced crude oil destined for Canada; (4) shipments to U.S. territories; and (5) California crude oil to Pacific Rim countries (EIA, 2018)

- The IEA expects Asia Pacific crude oil import needs to increase by 9 mb/d to around 30 mb/d by 2040, with strong growth in China, India and Southeast Asia

- The Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) plans to build the world’s largest integrated refining and chemical site, in Ruwais, UAE, tripling annual petrochemicals output to 14.4 million tons by 2025 (ADNOC, 2018)

- Nearly two-thirds of Asia-Pacific’s crude oil import needs (circa 21 mb/d) are now met by supplies from the Middle East

- By September 2016, U.S. tight oil production had fallen by 811,000 b/d (16 percent) from its March 2015 peak after a decline in WTI Spot price

- The alliance between the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and non-OPEC producers, announced in December 2016 to cut total oil production by 1.8 mb/d, is known as OPEC+

Growing market

Asia is expected to be the world’s main growth center for oil demand, at least in the coming two decades, given its population and economic growth. In this respect, Asian economies are going to need all the oil they can get and should have no difficulty absorbing output from both the Middle East and the U.S., and more from other regions as well.

Some have questioned the ability of Middle Eastern producers to meet growing Asian demand. The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts these countries will have only around 1 million barrels a day (mb/d) of extra export capacity as more of their production is diverted for domestic consumption.

Middle Eastern oil exporters are expanding their refining capacity to capture markets for refined products.

Middle Eastern demand for oil is not restricted to keeping buildings air-conditioned and cars on the road. A significant share of consumption comes from local refineries, which have expanded considerably in recent years as producers seek to cut their exposure to crude oil price volatility. When oil prices are low, exploration and production (the upstream part of the business) suffers, but refining (or downstream) margins typically benefit because crude oil is their feedstock. In this respect, the composition of exports from the Middle East to Asia may change but their volume will remain the same, especially in the longer term.

More importantly, the giant Middle Eastern oil exporters are expanding their refining capacity – both domestically and abroad – to capture export markets for refined products, not just crude. Saudi Aramco, for instance, has entered joint ventures and acquired stakes in refineries around the world, especially in Asia; since these refineries are configured to use Middle Eastern oil, they provide further protection for the Saudi national producer’s share in the Asian market.

Light competition

Differences in quality should also be taken into consideration. Not all crude oils are the same; they vary by gravity/density and sulfur content. U.S. tight oil is light (low density) and sweet (low sulfur content), while Arabian oil is typically medium/heavy and sourer. Refinery configurations are usually geared toward a specific type of crude.

With tight oil production expected to maintain its current growth momentum until the mid-2020s, one can expect U.S. oil exports to keep growing as well. But three additional factors need consideration here.

Facts & figures

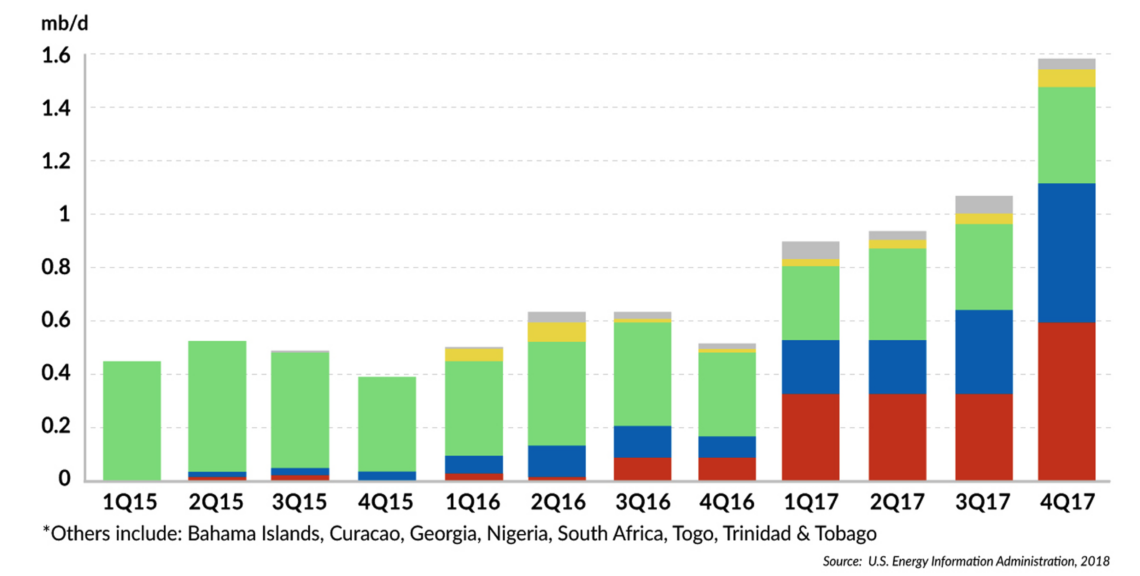

U.S. crude oil exports by region

First, if U.S. exports crowd other producers out of the regional markets, one would expect the first barrels to be replaced to be those in direct competition – namely, light sweet varieties, such as those produced in West Africa and Libya. In fact, at the onset of the shale revolution, West African producers saw their exports to the U.S. plunge by 80 percent between 2010 and 2016.

Second, international forecasting agencies have cast doubt on the ability of U.S. tight oil output to expand at its current rate beyond 2025, which could limit its subsequent export growth potential.

Finally, there are more attractive export destinations for U.S. oil, especially Latin America and Western Europe, given their geographical proximity. In contrast, when it comes to Asia, Middle Eastern producers have the logistical advantage. For instance, it takes less than 20 days to ship oil from Saudi Arabia to Asia compared to up to 35 days for U.S. exporters; the greater the distance, the higher the transportation costs. No wonder the International Energy Agency (IEA) said that “the long shipping distances make Asia the last destination for U.S. cargoes.”

Low-cost producer

There is plenty of oil around, and demand will determine where it goes. Asian consumers will simply buy from the cheapest source. In this respect, Middle Eastern producers have the fundamental advantage of being the low-cost producer who can always squeeze out the competition, if and when they choose to undercut their prices. It is unclear whether U.S. oil producers can withstand this price competition. The past few years have shown that the first oil to leave the market when prices fall has been U.S. tight oil. Middle Eastern oil only left the market by design because of the OPEC+ deal.

A hugely overlooked political element is that China wants to establish the renminbi as a truly global medium of exchange.

Some may argue that Middle Eastern countries have massive social obligations and therefore require much higher oil prices, at the so-called fiscal breakeven level, to balance their budgets. The plain fact, however, is that prices drive costs, not the other way around: when oil prices are high, the temptation for oil-rich countries is to embark on spending sprees. When prices are low, spending is cut back.

Political dimension

Besides the economic dimension, an important role in the oil trade is played by politics.

First, for Asian consumers, there is the all-important issue of security of supply. Some would argue that Asia will naturally look across the Pacific to reduce its exposure to the “volatile” Middle East. There is of course a legitimate point to be made here about diversification strategy. However, two caveats should be applied to such reasoning. Middle Eastern exporters sell their oil through long-term contracts, a practice Asia prefers due to the security and reliability such contracts offer. U.S. exports, by contrast, are typically spot cargoes, which can only address short-term demand fluctuations. Furthermore, the rather aggressive trade policy toward China recently adopted by the Trump administration is likely to make Asia’s largest oil consumer think twice about where to put its trust.

Second, a hugely overlooked political element is that China wants to use the oil trade to establish its currency, the renminbi, as a truly global medium of exchange. This would cement China’s position as a world economic power. State-dominated oil exporters in the Middle East would be more willing to strike deals in yuan than private exporters from the U.S.

Meaningful perspective

The key to understanding the competition between U.S. and Middle Eastern oil producers is distinguishing whether one is talking about the next year or two or about the longer term. Short-term analysts usually go overboard with their projections of change, ignoring that the oil markets are so big and their underlying forces so strong that one needs to take a longer view. Since U.S. crude exports started from zero, and not only in Asia, they will naturally show a little growth in the beginning.

The U.S.-Gulf rivalry is not a zero-sum, win-lose situation.

The U.S.-Gulf rivalry in Asia, however, loses its relevance in the global oil market. Besides, it is not a zero-sum, win-lose situation.

In the short term, the OPEC cuts have removed some Middle Eastern oil from the global market. In the longer term, however, there is still a worldwide glut. It will be a battle of the fittest. In this struggle, the low-cost producer will always have the edge.

[1] Some oil fields and destinations were exempted from the ban. See Factbox.