Khalifa Haftar overreaches in Libya

Khalifa Haftar, the military leader of one of Libya’s two battling governments, tried to short-circuit an UN-sponsored peace process by launching a lightning offensive against the nation’s capital, Tripoli. Instead of a successful blitzkrieg, his overstretched forces found themselves stuck on Tripoli’s outskirts.

In a nutshell

- Khalifa Haftar hoped his attack on Tripoli would end Libya’s civil war by a military knockout

- Its objectives were to seize the main levers of power: oil output and the capital

- The LNA commander overreached, however, putting himself in political jeopardy

In 1871, British general Garnet Joseph Wolseley wrote in his “Soldier’s Pocket Book for Field Service” that time and distance are the two elements on which all military movements are based. To these constraints, all good soldiers must adapt.

Based on this advice, Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar has got it all wrong.

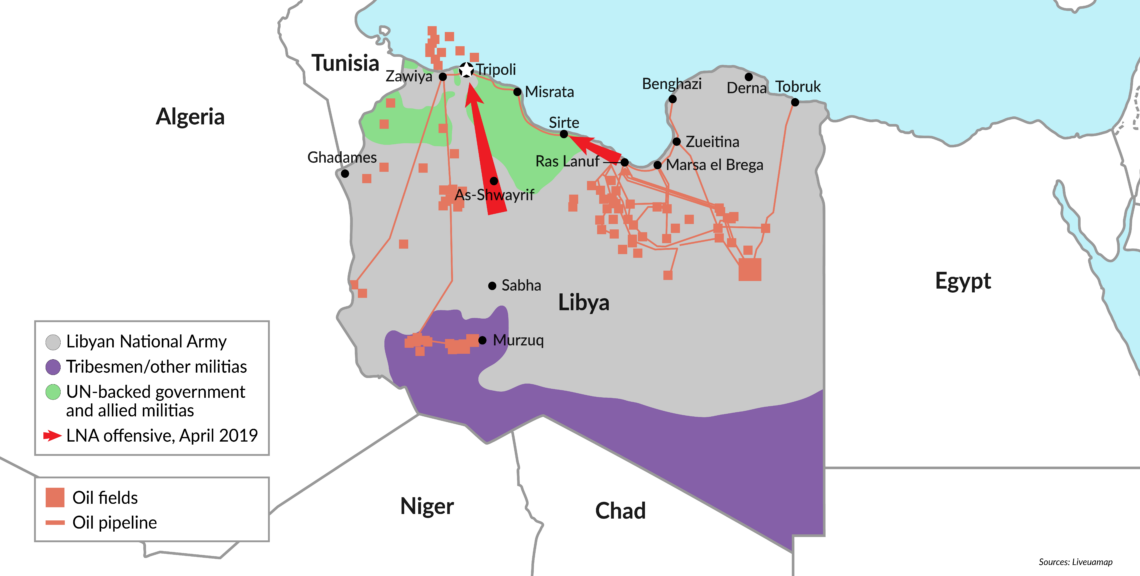

The military leader of the Tobruk-based House of Representatives, which is battling the United Nations-backed Government of National Accord (GNA) for control of Libya, launched an attack on the country’s capital, Tripoli, on April 4. The offensive began just 10 days before the National Conference, which should have brought together Libyans of all factions to discuss a constitutional framework for elections to unify the country, was scheduled to convene at Ghadames, in the southern region of Fezzan. This gathering was supposed to mark a fundamental step in the long and difficult process of national reconciliation. After years of back and forth, ordinary Libyans seemed ready to pull together after two rounds of civil war.

But not Mr. Haftar, who has always claimed that Libyans are not yet mature enough for a democracy and still need to be guided by a strong leader – namely, himself. Having eliminated a good part of his jihadi competitors in Benghazi (destroying many of the city’s neighborhoods in the process), the field marshal directed his Libyan National Army (LNA), which is, in reality, a cluster of militias, westward to Derna and on to the Sirte basin starting in mid-2018. It is interesting that he moved into the latter area not to fight against Daesh (as had the Misratan and other Tripolitanian militias, losing hundreds of fighters), but instead to seize control of the oil wells there.

Haftar’s assumption was that the road to victory lay in outflanking the GNA to the south, in the desert tracts of Fezzan.

There have been many reports of Russian intervention in support of this push, including rumors that some 300 military contractors from the Wagner Group (closely connected with military intelligence in Moscow) were involved. The LNA is also believed to have taken deliveries of Russian heavy equipment, including artillery, tanks, drones and ammunition. Some sources state that security for freighters unloading at Tobruk and Derna was provided by Russian personnel, who also monitored flows of Libyan oil destined for southern Europe.

Mr. Haftar’s advance in Fezzan, which got underway in January 2019, was consistently presented as an anti-terrorist operation. In fact, it was targeted at the main source of power in Libyan politics: control of energy exports. Careful negotiations with local armed groups preceded the offensive. The main objective was Libya’s largest oil field – Sharara, near Murzuq – a joint venture operated by Libya’s National Oil Corp. (NOC), Austria’s OMV, France’s Total, Norway’s Equinor (formerly Statoil) and Spain’s Repsol. The field, located 900 kilometers south of Tripoli, has a capacity of around 315,000 barrels per day, accounting for almost a third of Libya’s total production.

Facts & figures

Haftar's left hook

The field marshal had been preparing this advance methodically, for nearly two years. His strategic assumption was that the road to victory over the rival GNA lay in outflanking it to the south, in the vast desert tracts of Fezzan. Step by step, he stretched his army toward Sabha, a strategic outpost since the period of Italian colonization in the 1920s. Having established a logistical base there, he could make the final bound to Tripoli at the beginning of April.

Reality on the ground

Nearly three months have passed and the LNA remains stuck in Tripoli’s southern suburbs, around Wadi Al Rabie and the international airport. At the same time, forces loyal to Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj’s GNA have not been able to expel them. Both sides have used air strikes, with limited results. LNA drone attacks have caused some significant damage to the GNA, which also lost two fighter jets and one pilot captured. The opposing forces appear to be evenly matched. With each claiming the upper hand, there seems little likelihood of an early cease-fire.

During the second half of May, the LNA advanced toward Sirte again, in an apparent bid to shorten its supply lines through Ras Lanuf and As-Shwayrif to Bani Walid. Securing this axis would protect LNA spearheads south of Tripoli from being outflanked to the southeast and cut off. The offensive also serves a political agenda, as Mr. Haftar seems to be building a military administration in the east, appointing officers as mayors and putting an LNA commander and a company of 80 soldiers in control of the Ras Lanuf refinery, under the pretext of protecting it.

Why so reckless?

To make such a bold move, Field Marshal Haftar must have been pretty sure he would have the full backing of his sponsors, namely Egypt, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Russia and France. The last country found itself in a difficult position after Mr. Haftar’s reckless move. At the UN, all fingers were pointed out at French President Emmanuel Macron and, above all, at Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian, for their controversial Libya policies. However, it is one thing to support a possible “peacemaker” in Libya, someone who could potentially unify the country, and another thing altogether to embrace a warlord.

A second reason Mr. Haftar made his wager was his belief that he could carry out a successful blitzkrieg. He was clearly counting on a very short siege and few casualties, based on the fact that the militia cartels in Tripoli are profoundly divided and have been fighting each other for years. He probably also believed that the Misrata militias would not react or could be bought off with a useful compromise.

The LNA’s rapid move into Tripolitania has left it overstretched in desert terrain.

As was easily predictable, though, Tripoli’s militias quickly closed ranks against the invader, blocking the LNA just outside the capital. By mid-June, after more than two months of sporadic street fighting, the World Health Organization estimated that the death toll had risen to 691 dead and 4,012 wounded, of which 41 and 135, respectively, were civilians. More than 94,000 people have been displaced.

Too many mistakes

Once his forward momentum was checked, Field Marshall Haftar’s difficulties multiplied.

By all accounts, the LNA is the most powerful military force in the country, but its numerical strength is almost certainly a small fraction of its claim to field 75,000 troops. Most importantly, its rapid move into Tripolitania and Fezzan from its home base in Cyrenaica has left it overstretched in desert terrain, with no infrastructure and support services, dependent on a circuitous, 1,000-kilometer supply line for ammunition and reinforcements.

Even the Italians, during their conquest of Libya in 1922-1931, acknowledged the difficulties of conducting operations in such terrain by dividing Libya into two regions – Tripolitania and Cyrenaica – with different colonial governors, military commanders and expeditionary forces. There was some coordination between the two regional organizations, but each operated independently. The idea that a tiny and inexperienced army would be able to control such a vast territory, directed from 1,000 kilometers away in Benghazi, is rash in the extreme.

Several outside powers, especially France, have urged an immediate cease-fire. But for the past two months, Mr. Haftar’s answer has been a clear no – unless certain conditions (which have not been publicly disclosed) are met. Still, some information that has been kept from the public can help explain the LNA commander’s intransigence.

Mr. Haftar’s political position is far from secure. In the first days of the offensive, LNA losses were unexpectedly heavy. Around 100 of its soldiers were buried in temporary graves near Gharyan, 90 kilometers south of Tripoli. In the near future, it will be impossible for their families to reclaim the bodies. This created real turmoil in Benghazi, where the public had begun to hope for a peace settlement.

This blood sacrifice has raised the stakes significantly for Field Marshal Haftar. He must either conquer Tripoli or face the consequences. Winning even a favorable compromise with the GNA or the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) will not be enough. Some influential groups in Cyrenaica are watching Mr. Haftar closely and biding their time. If he stumbles, they could make their move.

Reasonable alternative

What makes the attack on Tripoli even more puzzling is that the LNA leader had a better option. Instead of forcing a siege that has already produced thousands of casualties and even more refugees, triggering exponential growth of anti-Haftar feeling, the field marshal could have presented himself as a savior of the homeland.

By letting the National Conference proceed, Mr. Haftar could have entered Tripoli without firing a single shot.

After all, the National Conference was scheduled to take place in Ghadames, an enclave in LNA-controlled territory. By letting the meeting proceed and keeping his finger on every step of the peace process, Mr. Haftar would have given himself an opportunity to enter Tripoli without firing a single shot – and received unanimous praise from the international community to boot.

As Sun Tzu, one of the finest military strategists ever, observed, the true test of a commander’s quality is not winning a hundred battles, but subduing the enemy without fighting at all.

Scenarios

The situation in Libya remains complicated and fluid. Once Mr. Haftar’s bid to seize Tripoli by a coup de main failed, however, there appears to be little prospect for a quick military or political resolution. In the longer term, three outcomes are possible.

1) The two Libyan competitors acknowledge that neither side can prevail militarily and return to the reconciliation process.

After months of house-to-house fighting with no significant result, Mr. Haftar and Mr. al-Sarraj agree to the cease-fire being demanded by the international community. This would be an opportunity to move back toward unification by constitutional and electoral means, opening the way for more international assistance for peacekeeping and reconstruction. But, as outlined earlier, any compromise at the stage would be viewed as a defeat for Mr. Haftar, making him vulnerable to political enemies in Cyrenaica. Some of the militia cartels in Tripoli and elsewhere may also resist the reemergence of a national government.

2) Khalifa Haftar wins.

After years of disengagement, and then support for the UN-sponsored peace process, the United States reversed course in mid-May, when President Donald Trump declared in favor of the LNA offensive. This appears to have been a serious miscalculation, especially since the presidential phone call to Mr. Haftar contradicted previous statements by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo that the U.S. would only accept a political solution.

Any encouragement of the field marshal’s ambitions will only prolong the fighting, producing more casualties and hardening Tripolitania’s hatred of the LNA leader. Perhaps the only gainers in this scenario would be the Tobruk government’s sponsors, especially Russia, Saudi Arabia and Egypt.

3) Fayez al-Sarraj and the Tripoli militias win.

The quickest way to pacify Libya would be for the U.S. to withdraw its support for Mr. Haftar. This would open the way for a political resolution, the only kind of victory the militarily feeble but internationally recognized GNA can count on.

A clear message from Washington could worsen the situation dramatically for Mr. Haftar, who might be abandoned by some of his historical sponsors but above all by the population of Cyrenaica. Growing tensions would be seen in Benghazi, where the field marshal may no longer find himself welcome.

Prime Minister al-Sarraj and the GNA seem to be banking on these developments if their new peace initiative (designed to replace the UNSMIL-sponsored process) is any indication. The point of their proposal is to show that since Mr. Haftar has removed himself from the Libyan political process, he should not be allowed back to the negotiating table. But that makes the rather major mistake of ignoring the LNA’s indisputable gains on the ground. Since the field marshal now holds a big chunk of Tripolitania, he must be part of any solution.

Dangerous vacuum

Over the next few weeks, there is little reason to expect the situation to change. But it is important to understand that no matter how powerful he has grown, time is not on Mr. Haftar’s side. Indeed, any protracted struggle could be fatal for his ambitions to be accepted in Tripolitania, while it will only increase discontent in his home base of Cyrenaica.

Already, in the south, the LNA’s concentration against Tripoli and Sirte has left a security vacuum. It is being filled by Salafist Islamic terrorists, from al-Qaeda to Daesh and Ansar al-Sharia. These were precisely the groups Field Marshal Haftar claimed were targets of his operations against Tripoli.