Haiti’s incomplete nation-building

The long struggle for independence has left insufficient resources to lay the groundwork of a functioning Haitian state.

In a nutshell

- Extreme corruption has left the nation of 11 million people destitute

- There are no state institutions able to tackle rampant gang violence

- The situation is unlikely to improve without foreign intervention

For centuries, Haitian intellectuals have attempted to trace the fundamental causes of their country’s economic underdevelopment and political instability. The legal scholar Emmanuel Edouard, for instance, attributed both to the perpetual struggle for the only source of wealth the country offered: the state. To work for the state, he wrote, “was to be in politics,” which, in turn, required officials to be “eternally distrustful, false and conniving.”

Whatever the reason, the fundamental question is whether any of this complex and ultimately dysfunctional political culture can be traced to the origins of Haitian nationhood. It is a sensitive and controversial topic. Most Haitians consider the early struggle for liberation from slave owners – the origins of the Haitian state – as quasi-sacred and beyond reproach.

It is historically correct and morally just to celebrate the slave revolt that created the first Black republic in 1804. But analysis cannot end there. These unique historical circumstances resulted in a system that revolves entirely around a single ruler, without institutions like a national army and state administration.

After independence, Haiti’s new rulers defeated the repeated foreign invasions of Spain, Britain and France. International isolation followed these battles for freedom. Even Simon Bolivar, to whom Haiti had granted asylum and assistance at the beginning of his struggle for independence against the Spanish, eventually distanced himself from Port-au-Prince. The cost of these violent conflicts was enormous and prevented the new state from developing the foundations needed for development.

The constant upheavals of these difficult years are evident in the life of General Francois-Dominique Toussaint Louverture, known as “the Father of Haiti.” First a slave, he then became a slave owner, a French monarchist, a French republican, a Spanish officer and eventually an ally of the British. Because all his efforts went into avoiding re-enslavement, insufficient resources were left for nation-building. He faced the conundrum which all future Haitians would face – because there was no centralized and dependable administration rewarding civilian and military followers, there was a perpetual struggle to gain control of the state.

Decades of bloody civil wars followed this dysfunctional beginning. Between 1843 and 1915, only one out of 22 presidents completed his term in office. New constitutions followed each change in administration. In 1877, after 25 years as British envoy to Haiti, Sir Spenser St. John wrote the country was “in rapid decadence … the whole attention of the country is devoted to mutual destruction.”

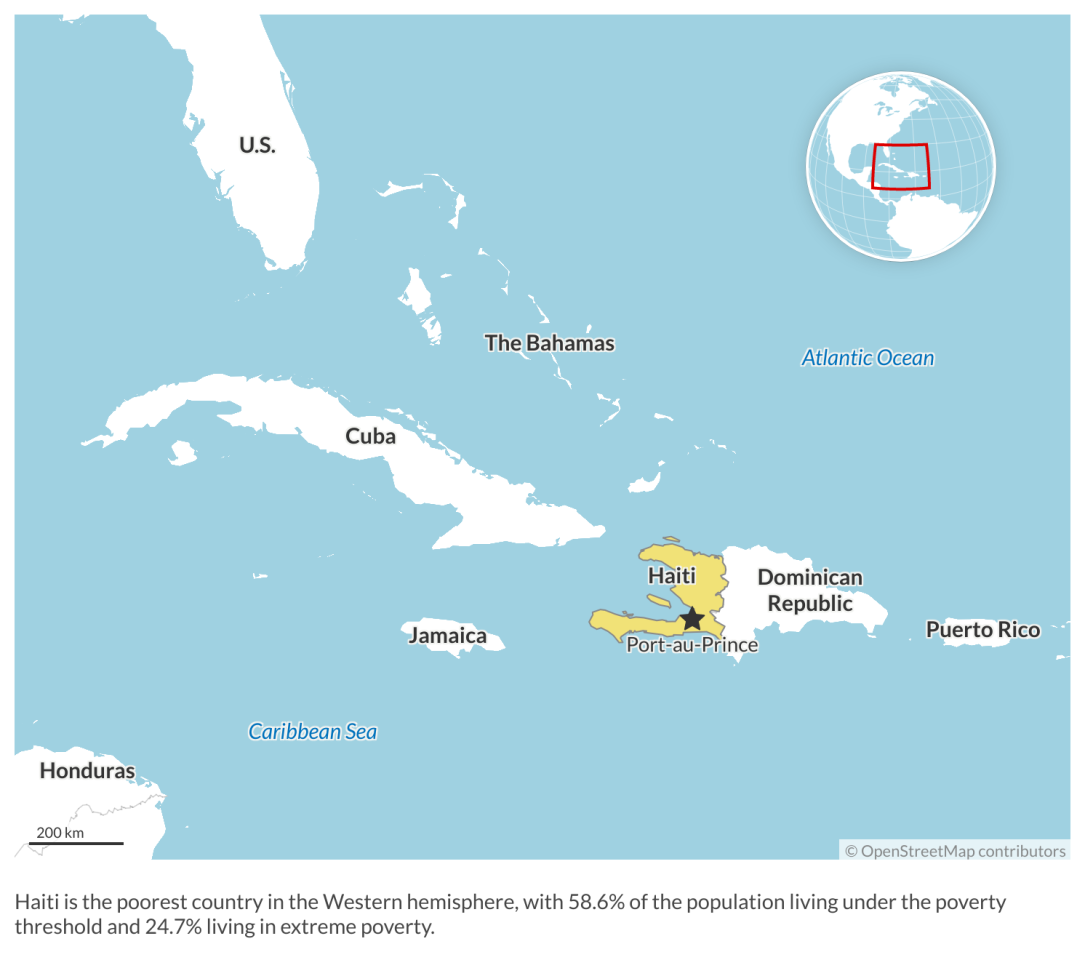

Facts & figures

By the beginning of the 20th century, all social and political order was on the way to collapse. The dire situation, and the fact that Germany was looking into establishing a naval base there, led the United States to invade in 1915. The occupation lasted 19 years. In 1926, a group of American liberals concluded that Haiti was perpetually torn between “revolution or acquiescence in tyranny.”

Tyranny did come, lasting decades under the Francois Duvalier dynasty (1957-1986). Then, in 1993 and 1994, U.S. troops intervened again amid growing chaos, to allow elections to proceed.

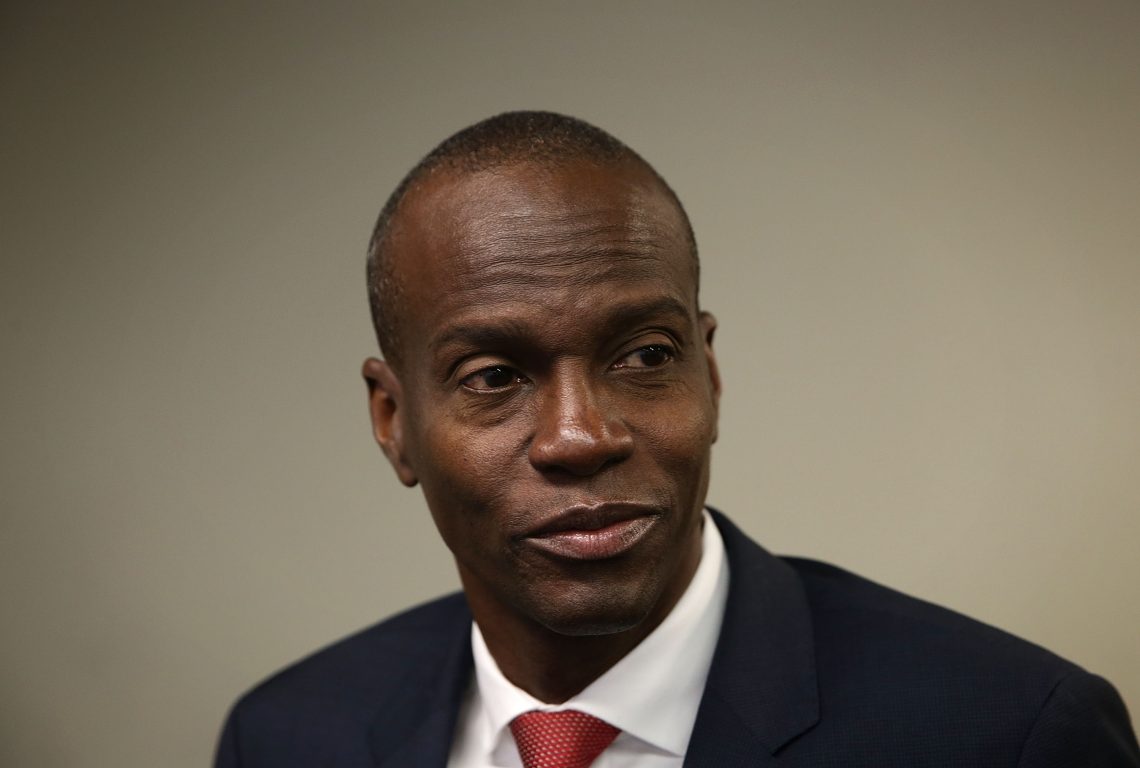

A new crisis after the assassination of Jovenel Moise

The long presence of a United Nations peacekeeping force (MINUSTAH, 2004-2019), plus an enormous infusion of external funds – first, billions of dollars to repair the terrible damage of the 2010 earthquake and then $2 billion in Venezuelan Petrocaribe aid – eventually did more harm than good. The early 2000s saw the rise of an even more vicious competition for state control.

In 2011, that violent struggle was won by Michel Martelly. Without ever explaining what was done with the funds that were pouring into the country, Mr. Martelly finished his term and handpicked his successor, Jovenel Moise. It is the subsequent assassination of Moise, and the murky role of two dozen Colombian mercenaries hired by Haitians in Florida, that led to the present national crisis.

This new crisis, however, has been made even more toxic by an additional factor: the exponential growth of gang-controlled areas. Protected by their political connections, these gangs control the drug trade and the smuggling of guns. They have different affiliations, but their goal is the same: laying the groundwork for their actor of choice to hold on to power. Haiti has a long history of armed groups fighting for control, and the current crisis is yet another instance of this phenomenon.

Facts & figures

Criminal gangs in Haiti

- Zenglendo: one of the most organized and powerful criminal gangs in Haiti, with a significant presence in the country's major cities and a reputation for violent tactics. The group is thought to have links to other criminal organizations both inside and outside of Haiti.

- Cacos: historical rebel group in Haiti known for fighting against U.S. occupation in the early 20th century.

- Tontons Macoute: historical paramilitary group in Haiti associated with political repression during the Duvalier regime (1950s to 1980s).

- G9: street gang based in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, known for drug trafficking and other criminal activities.

- G-PEP: gang based in Petit-Goave, Haiti, implicated in crimes such as murder, kidnapping, and robbery.

Hesitant to engage in another military intervention, foreign governments are now attempting to restore order through a series of legal measures against Haitian elites, all of whom, according to the Canadian foreign minister, are “profiteering” from the violence that is being weaponized by gangs in Haiti. On November 20, 2022, the U.S. and Canada announced sanctions for money laundering and the protection of drug lords, against Joseph Lambert and Youri Latortue, both at one time presidents of the Haitian Senate. Canada then imposed additional sanctions against several Haitian officials and former politicians.

In October 2022, faced with the fact that the police were not able to effectively tackle the gangs, de facto Prime Minister Ariel Henry called for the “immediate deployment” of foreign troops “in sufficient quantity to free the country of the gangs which had the island paralyzed.”

More on the Caribbean

Paradoxical Cuba: Three scenarios

A reborn Dominican Republic?

Scenarios

Any intervention will be met by claims that sovereignty is being violated and that the Haitian Constitution prohibits foreign troops on its soil. But the criminal gangs holding the political scene hostage – and their ties to foreign drug lords – make a mockery of those claims. Haitian politicians have historically resorted to foreign militaries to boost their power: from Henri Christophe’s personal guard of 5,000 to the mulatto elite’s appeal for U.S. Marines in 1914, to Aristide’s dependence on 60 mercenaries of the San Francisco-based Steele Foundation.

Any serious effort to reform Haitian governance will undoubtedly have to involve an even greater and more direct foreign presence. The reasons are evident: Haiti never had and still does not have the kind of public service necessary for durable development; and corruption, already widespread and endemic, has now become the basis of the state. Who controls the bounty granted by the state – not who feeds, clothes and heals the children or gets seed to the peasants – is what defines sovereignty in Haiti.

The situation is unlikely to change without legal reform, which could begin by addressing two fundamental issues.

Article 13 of the current Haitian constitution prohibits dual nationality. Haitian nationality is lost by adopting another nationality. This historical hyper-nationalistic posture excludes from citizenship the millions of the diaspora who have prospered in the U.S., Canada, France and throughout Francophone Africa. In 2019 that diaspora remitted about $2 billion, a large share of the nation’s $21 billion gross domestic product in 2021. Why deny dual citizenship to such a source of capital and talent?

A similar obstacle to development is Article 54, which specifies that the right to own real property is accorded to aliens living in Haiti “for the needs of their sojourn in the country.” Serious investors wish for contractual permanence and guarantees, not politically defined sojourns.

These hyper-nationalist laws had a certain defensive logic at the nation’s origins. In today’s globalized world, they are hindrances to development.