Iran’s ‘axis of resistance’ after October 7, Part 1: Hezbollah

Despite its bellicose rhetoric and regular missile attacks against Israel, Lebanon’s Hezbollah has strong incentives to avoid escalating into all-out war.

In a nutshell

- Hezbollah has tried to support Hamas without sparking a war with Israel

- Hassan Nasrallah would face domestic blowback to any Israeli retaliation

- Lebanon’s political crisis may give Hezbollah an off-ramp to the border standoff

This report is the first in a two-part series on Iran-backed militant groups amid the Israel-Hamas war. The second, on the Houthis in Yemen, can be found here.

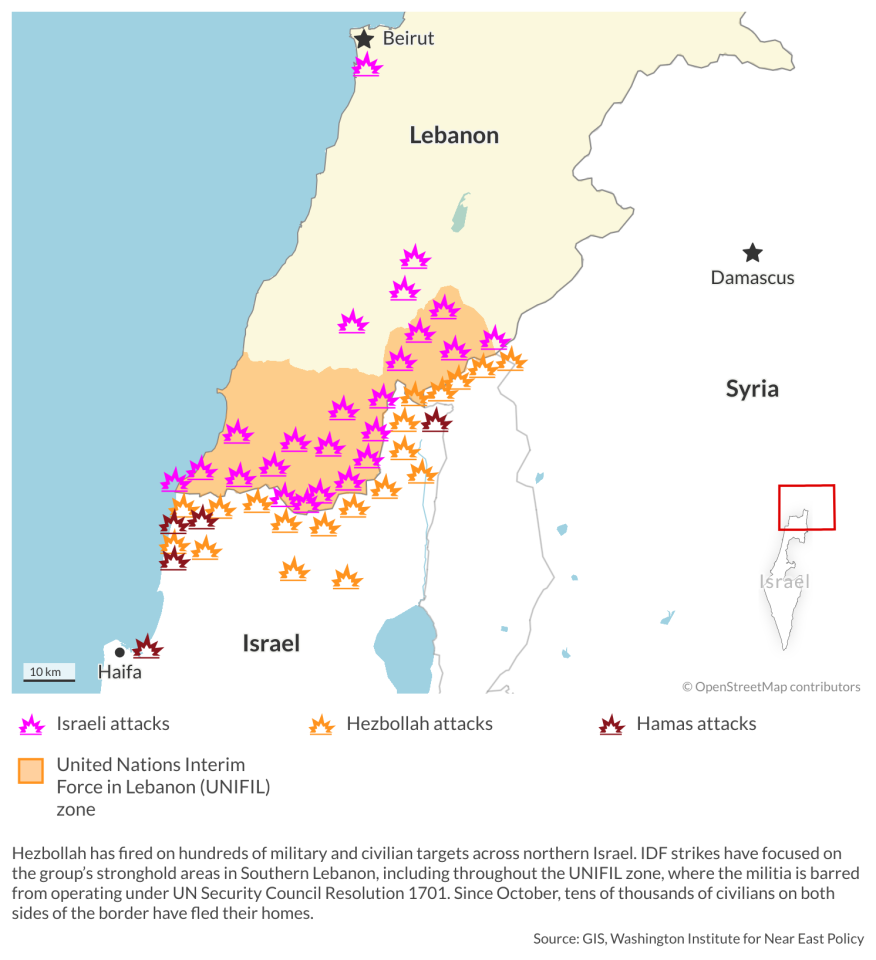

Following Hamas’s massacre in Israel on October 7, 2023, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) responded with air strikes against the group in Gaza. From that moment on, Israel’s northern Galilee region has come under fire from Hezbollah militants in Lebanon. The Houthi movement in Sanaa, Yemen, later joined the fray, firing missiles and launching drones at Israel and attacking vessels in the Red Sea.

Both organizations are supported and directed by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) of Iran. Their attacks, however, have so far been limited, stopping short of a full-fledged war. Syria and Iraq, two other Iranian satellites – as well as the Iranian regime itself – have largely kept out of the conflict. What is motivating these players, and what courses will they likely take?

Nasrallah responds

On October 8, one day afterthe outbreak of the war, Hezbollah began lobbing Katyusha rockets, mortar rockets, anti-tank missiles and drones into a narrow strip of Israel’s north, at first targeting military installations. The organization later began to strike civilian border settlements, and the entire Israeli border population was evacuated.

However, in view of the immense bombardment of the Gaza Strip by the Israeli Air Force and subsequently the military’s massive land invasion, Hezbollah’s response remained limited to the Galilee. For 26 days, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah remained silent in his bunker, pondering his options. For a charismatic television personality, staying quiet was extremely unusual behavior.

On November 3, at long last he spoke. Mr. Nasrallah felt obliged to explain why, after Hezbollah had publicly committed itself a few months earlier to supporting Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad in Gaza, it had only managed limited border attacks for almost a month. Some Arab media outlets began to criticize the group’s leader for abandoning the Palestinian and Islamic struggles. Maintaining his image as a very prominent (if not the leading) global Islamic leader is of tremendous importance to Mr. Nasrallah, and he had to deflect the blame.

Every southern refugee in Beirut and every destroyed farm or house is a millstone around Mr. Nasrallah’s neck.

The decision to attack on October 7, he declared, was “100 percent Palestinian.” Those who carried it out “kept it secret from everybody.” This implied that Hezbollah was caught by complete surprise and could not have prepared for the war. The battle, Mr. Nasrallah emphasized, “is purely Palestinian, for the Palestinians” – in other words, not for global Islam.

At the same time, he pointed out that Hezbollah was not sitting idle. Its military operations continued to pin down much of the Israeli military, which must split its forces between Gaza and the northern Lebanese front. In a second speech six days later, Mr. Nasrallah called the war a victory for Hamas, while at the same time demanding an immediate cease-fire. He was surely aware that Hamas’s supposed victory, even as defined by mere survival, was not yet guaranteed.

Hezbollah’s restraint

Between October 8 and the final days of 2023, Hezbollah increased the volume of its attacks into Israel by some 20 percent. The IDF followed suit, but neither side breached a tacit agreement to keep the fighting contained. From the Israeli government’s point of view, a limited response to the limited Hezbollah attack, while a debatable approach, did not represent a breach of faith with the Israeli public. Avoiding a full-on war with Hezbollah and the opening of a second front, even though this was demanded by the military and minister of defense, was in line with previous Israel policies. But for Hezbollah – in view of its declared total commitment to the Palestinian cause and Iran’s “resistance front” – settling for a limited war was surprising, even humiliating.

Why did Hezbollah not keep its promise to Hamas and launch a total assault on Israel, bombing its military and civilian airports and main population centers? There is no practical obstacle; while in the 2006 war with Israel, the group managed to launch daily some 150 warheads (of poor accuracy) into Israel, today it can cover the whole country with at least 1,500 missiles and rockets per day, not to speak of numerous killer drones. The group also has a few hundred highly accurate, GPS-guided munitions. Yet Hezbollah has more than one Achilles’ heel, which explains its restraint.

Facts & figures

In the immediate term, Hezbollah was taken by complete surprise, as Hamas had not coordinated its attack with them. To launch a total assault, including a land invasion into Israel, Hezbollah would have needed several days to prepare. Had they done so and joined Hamas on October 7, the disaster in Israel would have been immeasurable. But by then, the IDF was ready for it.

Moreover, after any broad Hezbollah attack, no matter how devastating it might be, Israel’s air force, artillery and drones would devastate Lebanon’s infrastructure, even without a land invasion or any American involvement. Without electric power, seaports, airports and bridges, Lebanon would come to a standstill. Mr. Nasrallah is dedicated to Israel’s destruction no less so than Hamas commander Yahya Sinwar. But unlike the latter, he has additional commitments.

Casualties

For one, contrary to Mr. Sinwar, Hezbollah’s Nasrallah feels a deep responsibility for his soldiers. Shia society in southern Lebanon, the organization’s power base, is very sensitive to casualties. During its involvement in the civil war in Syria, the militia suffered more than 2,000 deaths. This led to great resentment in the community, which protested the slaying of their sons in a war that was not their own.

By December 30, Hezbollah had admitted the loss of 132 fighters. By then, Hamas had already lost several thousand. While Mr. Sinwar did not even flinch, this placed Mr. Nasrallah in a very difficult position, because he is accountable to the families. Indeed, his second war speech on November 11, Hezbollah’s “Martyrs’ Day,” was dedicated to the fallen militants. Despite its fire and brimstone, they were pained remarks. To indicate that they did not die for Gaza but for a greater cause, he called the dead “shahids (martyrs) of Jerusalem” and opened with a Koranic verse of consolation: “Do not consider those who have been killed for the sake of God dead: they live with their Lord and all their want is filled.” One of Mr. Nasrallah’s weaknesses is that, after his Syria adventure, every Hezbollah fighter killed in a war perceived by his community as unnecessary harms his stature.

Collateral damage

Furthermore, while Yahya Sinwar is willing to sacrifice most Gazans for his ideology, Mr. Nasrallah also feels deep responsibility for the large Shia community in southern Lebanon and Beirut. The mass exodus and subsequent destruction there during the 2006 war caused him such political damage that he apologized for initiating the crisis.

By December, the present war had already forced more than 80,000 Israelis on the Israel-Lebanon border to flee their homes. But in Lebanon, too, around the same number have left the border area, and more still may leave. The limited conflict is already paralyzing Lebanon’s south. During a weeklong cease-fire in late November, refugees who had fled the villages of southern Lebanon returned and were aghast at the destruction of their homes and farms. Press reports described many “angry souls” who severely criticized Hezbollah, which launched a damage control operation by promising compensation.

A further expansion of the conflict would be unpopular. Every southern refugee in Beirut and every destroyed farm or house is a millstone around Mr. Nasrallah’s neck. In a broader war, Lebanon’s Shia-majority south will be completely evacuated, and then devastated. The Shia of the Jabal Amil region in southern Lebanon live in their historic homeland, where they arrived from Yemen as early as the 9th century. They are living on their own land; they have no yearning for a paradise lost. Mr. Nasrallah’s battle cry of “liberating Jerusalem” is important to them, but their homeland is immeasurably more so.

Political capital

Demographically, Shia only make up some 40 percent of Lebanon’s population. They cannot indulge in Mr. Nasrallah’s Khomeinist ideology as if Lebanon were theirs alone. If the Hezbollah chief does not want to sit on the bayonets of his fighters, he must form a political coalition with Christian, Druze and Sunni partners. So far, he has been doing precisely that. He cannot sacrifice Lebanon as Mr. Sinwar is sacrificing Gaza. It is important for him to be considered the “Defender of Lebanon” no less so than the “Liberator of Jerusalem,” and his domestic situation today is more difficult than ever.

In 2019, Lebanon’s economy collapsed, which many Lebanese blamed on Hezbollah. Since then, demonstrations have erupted against both the militant group and Iran. In the May 2022 general elections, Hezbollah’s coalition lost its parliamentary majority. Neither national bloc today has a majority, so there is currently no elected government or president, but both sides have representatives capable of switching camps. Despite a general identification with the Palestinian cause, for most Lebanese, the notion of their country being sacrificed again, as it was in 2006, is anathema.

As early as October, provisional Prime Minister Najib Mikati confessed that the Lebanese government has no way of preventing Hezbollah from starting a full-fledged war. Mr. Nasrallah seems to be losing his supporters in the non-Shia communities. In late December, Wiam Wahhab – leader of the Arab Unification Party, a small, pro-Hezbollah Druze party – demanded an end to Hezbollah’s war against Israel. He admitted that he was tired of the fighting; as he put it, Mr. Nasrallah’s support for Hamas does not really affect the course of the war in Gaza, and the price Lebanon pays for it is too high. This criticism met with a tsunami of condemnation, but that only gave his position wider publicity.

It is even possible that opposition to war will enable the parliament to elect a government and president who are not Hezbollah henchmen. The new president may demand the militant group’s withdrawal as well as its disarmament. In mid-January 2024, Mr. Nasrallah managed to push Prime Minister Mikati to declare that calm in southern Lebanon would not be possible so long as fighting in the Gaza Strip continues. Whether this statement was half-hearted or genuine, it did not reflect the wishes of many if not most Lebanese.

Regional factors

Mr. Nasrallah must also take into consideration his Iranian patrons. They have made it clear to him that, now, they do not want him to endanger Hezbollah’s existence and stature in Lebanon. Tehran has a timetable of its own.

Meanwhile, the United States is mediating a land-border agreement between Israel and the interim Lebanese government. The October 2022 maritime-border agreement signed by the two sides was highly popular in Lebanon, and received Hezbollah’s blessing. Most Lebanese see a similar agreement for the land border as a boon for stability, and Israel is willing to negotiate. Escalating the current war will prevent such an agreement.

Resolution 1701

Mr. Nasrallah succeeded in anesthetizing the United Nations Security Council’s Resolution 1701 of August 2006. The resolution stipulated that he would disarm and withdraw his forces from southern Lebanon, and that Lebanese Armed Forces and the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon would be deployed there. This decision was approved by the Lebanese government, and Mr. Mikati reiterated his government’s commitment to it during the present conflict. But Hezbollah has ignored it.

When it opened fire in October, Mr. Nasrallah awoke this resolution from its slumber. It now functions as a Sword of Damocles over his head – giving Israel international legitimacy to use force, at least to push Hezbollah out of southern Lebanon.

In Beirut, the Lebanese Forces, a Christian bloc and the largest party in the country’s parliament, are already calling for the immediate restoration of Resolution 1701 as the only way to provide “stability and security to Lebanon.” If Mr. Nasrallah initiates total war, this will further legitimize any Israeli effort to occupy southern Lebanon, however briefly, and push Hezbollah’s fighters north.

Scenarios

Despite the incremental escalation of hostilities, neither Israel nor Hezbollah is interested in an all-out war at this juncture. However, looking a few months ahead, Israel will not be able to tolerate Hezbollah fighters on its northern border. The dread in the north of a possible Hamas-style commando raid – with the mass rape, mutilation and massacre of Israeli citizens in the Galilee – is palpable. And this fear will never fade; the Jewish people have a long memory.

Unless Resolution 1701 is implemented, at least as it concerns the withdrawal of Hezbollah, northern Israeli refugees will not return to their homes. This means that if Mr. Nasrallah does not order his fighters to withdraw north of the Litani River and allow the Lebanese army to take their place, the IDF will do it for him. At least, this is what Israel’s top security officials have said, and the government will find it very hard to renege on such a commitment. For Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, to be seen as responsible for the civilian abandonment of the northern Galilee is unthinkable.

Hezbollah’s leader is aware of this, but he cannot accept Resolution 1701, even just the withdrawal provisions. In addition to bringing deep humiliation, it could give the Lebanese opposition an opening to demand the group’s disarmament as well. Instead, Mr. Nasrallah might be able to live with a new de facto reality that Israel’s measured escalation is already working to create – one in which Hezbollah fighters and positions are not seen within some 30 kilometers north of the border. Both sides would declare victory. Israeli civilians would return to the border zone under heavy long-term military protection and an IDF commitment to retaliate harshly against any infringement of the ceasefire. Hezbollah could cast it as a civilian homecoming, since many of its fighters live in the southern villages.

To avoid an all-out war, Iran may advise Mr. Nasrallah to accept such a deal, in the belief that it can be reversed incrementally in the coming years. Such an understanding could be solidified if Israel and Lebanon sign an American/French-mediated land-border agreement, similar to the maritime deal struck in October 2022. Presently, though, negotiations over such an accord do not look very promising.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.