Iran, Saudi Arabia and Gaza: Shattered expectations

Amid the war between Israel and Hamas, the modest deal for Saudi-Iranian rapprochement has emerged as a stabilizing force, for now.

In a nutshell

- Saudi Arabia, Iran are nominally maintaining relations despite differences

- Tehran however appears to be seeking to undercut Riyadh

- The Israel-Hamas war is testing the sincerity of their rapprochement

Iranian and Saudi officials were admittedly far-seeing when they officially restored diplomatic ties last April. Some observers had questioned the scope and significance of the agreement, which was couched in general terms and contained no binding clauses. Today, three months into the war between Israel and Hamas in the Gaza Strip, the full significance of the reconciliation has become clear. The two regional powers can now maintain a minimum threshold of diplomatic relations, despite ongoing differences. However imperfect, the deal is a stabilizing factor for the entire Middle East, at least for now.

About a month after the fighting erupted in Israel and the Palestinian enclave, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Iranian President Ibrahim Raisi met face-to-face on the sidelines of a joint Arab-Islamic summit on Gaza in Riyadh. Since then, several bilateral initiatives have gotten underway, including a visa waiver program to increase the number of visitors and encourage business travel between Iran and Saudi Arabia. The deputy governor of the Central Bank of Iran, Mohammad Aram, also visited Riyadh to develop banking relations between the two countries. Although these developments are minor compared to the war, they demonstrate the determination of both countries not to be caught up in the current instability.

Each nation is now observing the other according to the yardstick of its own interests, with the parties agreeing to reconcile in the hopes that the situation will one day improve.

Tehran’s role in the conflict

The war in Gaza has created an unexpected shockwave. If Saudi diplomats had been aware of the October 7 attack planned by Hamas, they would certainly have put pressure on Tehran to use its levers in Gaza to prevent the tragedy. Riyadh would have intervened with conviction, because of its intimate knowledge of the Palestinian question and the energy it has spent on it. The regime is convinced that violence will only lead to negative outcomes.

In 2002, Saudi King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz’s Arab Peace Initiative offered Israel peace in exchange for the Palestinian territories. This willingness to mediate remains, despite the tragedies and failures of earlier peace processes. Saudi Arabia understands that as a custodian of holy Muslim sites, it is held in special esteem by the Palestinian people, who seek to make Jerusalem, Islam’s third-holiest city, the capital of a future state.

After the October 7 attack began unfolding, Saudi Arabia bitterly noted that the Iranian regime had apparently been unable to anticipate (or unwilling to prevent) the Hamas attack. Now, between the catastrophic consequences for the people of Gaza, the cost of the fighting and the likely exorbitant price to rebuild the enclave, Iran’s strategy is coming into question.

There are many signs that Iran is pursuing an agenda aimed at undercutting Saudi Arabia, despite the recent signals of rapprochement.

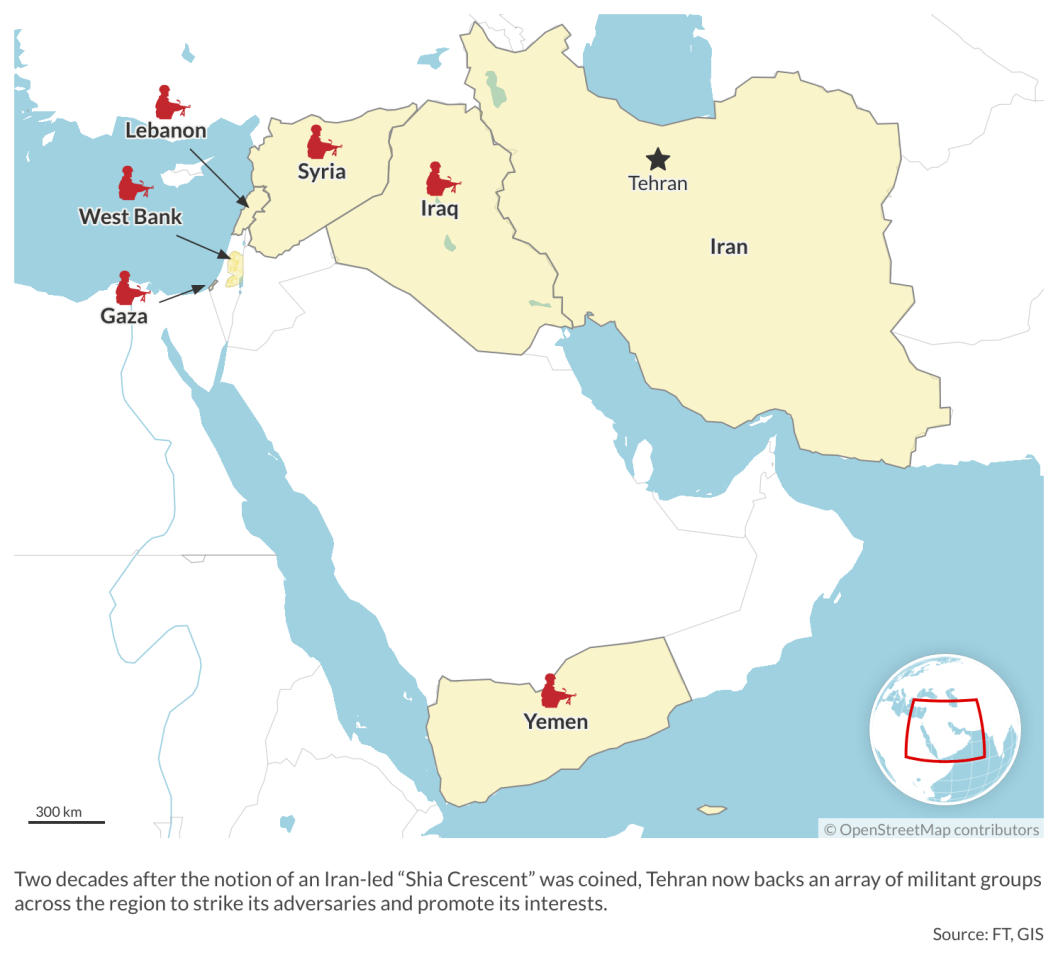

Tehran claims it is not a cobelligerent, but it uses bellicose, virulently anti-Israel rhetoric that is echoed by its militias across the Middle East – including some now actively engaged in attacks on Israel, like Hezbollah or the Yemeni Houthis. That is a second, equally bitter observation for Riyadh: the Arab world, where Saudi Arabia should have natural strategic depth, is now crisscrossed by armed groups loyal to the Islamic Republic of Iran. Whether based in southern Lebanon, the West Bank and Gaza, Syria, Iraq or Yemen, what they have in common is that they get their marching orders from Tehran.

The concept of a “Shia Crescent” may have seemed questionable when King Abdullah II of Jordan coined it in an interview with the Washington Post in 2004; today, it is all too relevant. The activities of Iran’s allies are being felt across the Middle East. Diplomats fear the risk of regional destabilization. Jordan has just strengthened its military presence on the Israeli border. Reported landings at Beirut’s airport and the Lebanese Army’s Hamat Air Base suggest the possible delivery by NATO members to Lebanon of electromagnetic systems to jam the communications of pro-Iranian militias there.

Over a hundred attacks have been carried out against American bases in both Syria and Iraq since October 7. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken visited Baghdad to demand more serious security measures, but promises made to him have not been kept.

Facts & figures

In the face of rising tensions, Tehran could have been a voice for calm and restraint. Instead, its militias have stepped up their activities in Syria, where Saudi diplomacy had sought to regain influence and cooperate with Damascus. The disappointment is all the greater because Saudi Arabia worked to bring Syria back into the Arab League last year. The results have been discouraging; Bashar al-Assad’s regime has not sent any signal of openness to the Saudis, other than a few general statements.

Syria remains under the thumb of its closest allies: Moscow and Tehran. Hardly a day goes by without local sources reporting that Iranian Revolutionary Guards have set up new headquarters in Deir ez-Zor, before leaving in a hurry for fear of air strikes. Meetings are organized with Iranian envoys. Fighters from Iraq, belonging to pro-Iranian factions, pass through the region on their way to the Israeli border. Iranian aircraft land in Palmyra. Weapons caches move through the country, from houses to ice cream factories and onward toward conflict zones. The situation is so heated that Russia sent a team of mediators from its military base in Khmeimim to ease tensions. In the early months of the war, Moscow feared that Syria would go up in flames; Russia used its contacts on the ground to set up informal dialogues with the clans, tribes and armed groups in Deir ez-Zor in an attempt to calm tensions.

The Iranian strategy

There are many signs that Iran is pursuing an agenda aimed at undercutting Saudi Arabia, despite the recent signals of rapprochement on the surface. Its lack of determination to prevent the outbreak of war in Gaza is just one case in point. Saudi Arabia was also engaged in talks with the Houthis to end the violence in Yemen, another very fragile process; now, the Yemeni rebels are firing rockets into Israel, leading to a buildup of the U.S. Navy presence in the region. In short, everything that Saudi diplomacy had patiently set in motion in recent months has been thwarted.

What is Ali Khamenei’s Iran up to? Is this a new round of the double game in which Iranian strategists specialize? Tehran pretends to be satisfied with the Saudi reconciliation agreement, which provides the advantage of helping neutralize its rival. Meanwhile, the regime continues to pursue a patient strategy of embedding itself in power structures throughout the Middle East, aimed at regional hegemony.

For a long time, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf monarchies served as triangulation points for Arab disputes. It was there that enemies met, tongues were untied and solutions were found. But since 2011, when the Arab Spring uprisings failed, there has been a change in polarity. A growing number of rebel movements, both Sunni and Shia, praise the Iranian Revolution as an Islamist success. Tehran’s resilience is celebrated – as are its theological intransigence, its legislative commitment to a simpler brand of Islam and its operational capacity to wage jihad, never settling for the status quo.

Read more on Iran

Geopolitical wrangling over Iran’s nuclear program

A debate has opened within the Arab protest movement, with some asking whether Iran is manipulating armed groups to “serve Persian objectives.” Tehran’s methods are facing scrutiny, as one former jihadist leader confided: “We refused Iranian funding because it demanded Shiism.” Others note that the alleged de facto leader of al-Qaeda is said to be in Tehran, as corroborated by U.S. intelligence. This is in keeping with the ideological vision of Osama bin Laden, who dreamed of a global jihad that would transcend Sunni-Shia antagonism.

Other discordant voices can be heard. In a sermon delivered in Lebanon in October, the founder and ex-leader of Hezbollah, Subhi al-Tufayli, argued that Iran was pursuing a war strategy that runs counter to the interests of the Muslim community.

Scenarios

The Gaza crisis has highlighted the reality of the balance of power in the Arab and Muslim worlds. For Tehran and Riyadh, it is an opportunity to test the mutual sincerity of their reconciliation. Each can cite reasonable grounds for either maintaining the new diplomatic channel or abandoning it; it is all a matter of political will. So far, Iran and Saudi Arabia have chosen the path of reason and agreed to coexist despite their differences. But that is hardly set in stone.

Carrying on

Bilateral relations are unlikely to break down for the time being. Iran and Saudi Arabia are fully aware of their mutual antagonism, but have decided to live with it. Their diplomatic corps will continue to provide “minimum services”: advancing initiatives on economic and other issues, sticking to general remarks when forced to speak out on the war or working together on less divisive issues like restoring peace in Sudan.

Sideline meetings would continue at political summits, but each side’s respective allies would demand clarification of Riyadh’s and Tehran’s true policy positions, especially on security issues. While countries like Syria and Iraq are happy with the reconciliation, as it simplifies their relations with two regional giants, states like Lebanon are much more cautious, torn between the pro-Western bloc and Iran’s influence.

Deterioration

In this scenario, relations between Tehran and Riyadh slowly deteriorate. A complete rupture is still ruled out, as this would be tantamount to reneging on the signed reconciliation agreement, but misunderstandings develop as the climate grows increasingly poisonous. It becomes clear that the reconciliation agreement is a mostly empty one. The only positive aspect is that the two countries can now talk to each other in real-time and exchange views. But all recognize that one day some unexpected incident will cause a new breakdown.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.