The rise and fall of India’s vaccine diplomacy

In early 2021, India was hailed as a hero for its successful vaccine diplomacy. When a second Covid wave hit, the country stopped being a global exporter of vaccines. If it does not get back on track by the end of this year, Beijing could take advantage.

In a nutshell

- India has halted its export of vaccines – to the detriment of its image

- New Delhi could allow exports again by the end of the year

- Other countries, like China, may pick up the slack in the meantime

For the first three months of the year, India was toasted as the world’s Covid-19 savior, exporting millions of vaccines across the world. Hit by a second wave of the virus, India halted all exports in mid-April and is now trying to import vaccines. This fall from grace has led to an outpouring of criticism against the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, aggravated existing vaccine shortages in places like Africa, and given China an opportunity to exert more soft power. However, the global Covid vaccine story has several more chapters left, and India could become a net exporter again by winter if it can persuade the United States to strike a partnership.

Export power

A sharp drop in Covid-19 cases between September and February lulled the Indian government into rolling out a leisurely vaccination program that reached barely half a million doses per day by the end of January. The country’s two Covid vaccine manufacturers – Serum Institute of India (SII), which made the AstraZeneca jab under license, and Bharat Biotech – were producing four million doses a day. The excess doses began piling up, some of which were threatening to expire. India believed it had the leeway to export.

Many of these doses were already marked for overseas use. A large portion of SII’s production was reserved for the Gates Foundation-backed Covax scheme for poor countries. The firm also signed commercial sales to specific countries allowed under a marketing agreement with AstraZeneca. New Delhi was flooded with requests from more than 90 foreign governments.

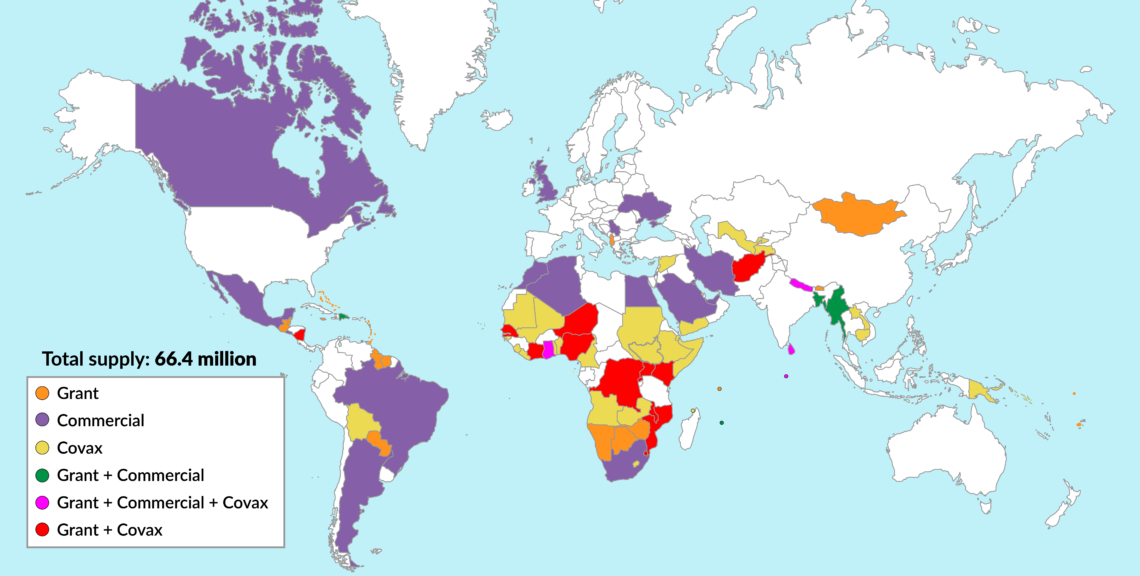

In January, Prime Minister Modi announced the Vaccine Maitri (“Vaccine Friendship”) program of shipping doses to countries in need. By the time an export ban was imposed in mid-April, Indian firms had exported 66 million vaccines: 54 percent of them commercially, 30 percent under Covax and 16 percent as grants.

India was lauded internationally, not least because of the contrast with other vaccine-manufacturing centers. Europe and the U.S. were consuming almost all their domestic production. Chinese vaccines were struggling to get regulatory approval.

Vaccines were provided to middle-income countries where India saw an opportunity to create a profile from nothing.

India’s vaccine shipments were not arbitrary. Neighbors were the priority: India delivered more than 10 million doses to Bangladesh, the single largest recipient. Vaccines were also provided to middle-income countries in Africa and Latin America, island nations in the Caribbean and South Pacific and some Central European countries, often ones in which India saw an opportunity to create a profile from nothing.

An underlying rivalry with China often manifested. When Paraguay, one of the few countries that recognizes Taiwan, began hunting for Covid vaccines, Beijing immediately offered to provide them, but with an obvious rider – rescinding its support for Taipei – attached. Though India lacked an embassy in Asuncion, Paraguay’s foreign minister appealed to New Delhi. India sent 200,000 doses and was publicly thanked by the Taiwanese foreign minister.

Crucial mistakes

New Delhi’s primary error was to not use the past year to increase vaccine production capacity. Its health ministry, obsessed with keeping down domestic medicine costs, set local Covid-19 vaccine prices at $2. Skeptical about a second wave, it also refused to make assured bulk purchases and dithered on a capital subsidy when SII and Bharat Biotech asked for help to fund expansion plans. The export ban was the last nail in the coffin, discouraging the private sector from even preparing for future expansion – including booking necessary ingredients from overseas early on.

When cases surged in March, a panicked New Delhi brought all vaccine exports to a halt. The Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned India “it was not an island.” Prime Minister Modi was inevitably more concerned about the problem he faced at home as India became the Covid epicenter, accounting for over half the world’s recorded new cases. Belatedly trying to ramp up production, New Delhi gave capital subsidies to manufacturers, partially freed up prices, fast-tracked approval and testing, and began looking for overseas sources.

Facts & figures

So late in the game, the shelves for Covid-related material were largely empty. The biggest obstacle was importing enough ingredients from other countries to improve vaccine-making at home. The largest source was the U.S., which had restricted exports for many Covid-related substances. It took considerable diplomatic effort to persuade Washington to partially lift the restrictions.

Ramping up

India is currently looking at a shortage of vaccines until the end of July, with a leap in supplies from August onward. The Indian government has declared it believes it will produce two billion vaccine doses in the period between August and December, in theory enough to cover 80 percent of India’s population. Officials privately admit this is a best-case scenario; it assumes that there will be no supply chain disruptions and that all new vaccines will receive regulatory clearance.

India has three vaccines cleared by regulators. Over June and July, the country will produce about 240 million doses of these. In August, production will rise to 170 million, while five new vaccines are expected to receive clearance and add 40 million more doses. From September to December, dosage production will have risen again to about 450 to 500 million a month. All of this will be supplemented by tens of millions of imports, the purchase of which is being negotiated.

India could begin exporting vaccines again, possibly as early as October, but more likely by December.

Industry sources predict everyday production glitches will reduce these numbers by about 20 percent. Officials say India could conceivably begin exporting vaccines again, possibly as early as October, but more likely by December. The most important prerequisite to achieve such numbers is a steady flow of the chemicals and equipment needed for such an enormous expansion of production.

About 250 ingredients from as many as 30 countries go into making a vaccine, the bulk of them from the U.S. New Delhi spent months arguing to Washington that it is in America’s and the world’s interest to keep the Indian vaccine-making machine going full throttle. In early June, the Biden administration announced it would lift restrictions on sending some necessary materials to India, though some production constraints remain in place.

Scenarios

In the worst-case scenario, India would struggle to ramp up vaccine production beyond 250 million doses a month. This would be true if new vaccines failed to overcome regulatory hurdles and, worst of all, imported ingredients failed to arrive in sufficient numbers. India would have just enough doses for itself but would cease to be a player in the international pandemic response. The U.S. or China would pick up the slack. A nightmare would be the arrival of a Covid-19 mutation immune to one or more of the vaccines. So far, none of this seems likely. Based on their technology, at least two of the new vaccines seem almost certain to receive clearance.

The more likely scenario is that India falls slightly short of its two billion dose mark, enough to bring its present Covid problems under control by year-end. But there would be little in the way of an exportable surplus until the last few months of 2021 or early next year, by which time India would be one of several global exporting hubs. The brief period when India was labeled “pharmacy of the world” would prove a flash in the pan. But at least the country would have brought Covid under control within its borders and would be able to help in the immunization of the rest of the world.

The most positive scenario is already starting to emerge in India’s diplomatic consultations with the U.S., Japan, the United Kingdom and, to some extent, the European Union. These discussions assume the world will need tens of billions of vaccines, including boosters, for several years. Plans are beginning to emerge for the world’s major democracies to pool their resources – technological, financial and otherwise – and generate a constant flood of doses for the world.

Elements of this strategy are already evident in the recent Quad working group on vaccines and the pharmaceutical elements of the recent bilateral road map signed by India and Britain. The last piece fell into place when the U.S. ended its Covid isolation in June and announced its intention to export vaccines and help others make them. These plans would help reinvigorate India’s capacity, but also marginalize China’s efforts to emerge as the world’s next vaccine savior.