How India has managed its relationship with Donald Trump

The burgeoning relationship with the United States is a crucial part of India’s foreign policy. With the election of Donald Trump as president, New Delhi was unsure what to expect. So far, it has leveraged its strategic importance and the leaders’ friendship to its benefit.

In a nutshell

- India sees plenty of positives in U.S. policy under Trump

- Climate and trade are two crucial sticking points, however

- The 2020 election brings uncertainty to U.S.-India relations

India’s government, like most around the world, was surprised by the election of Donald Trump as president of the United States in 2016. India had been drifting closer to the U.S. over the previous two decades thanks to common concerns about China, a deepening economic partnership and the clout of the Indian-American community. Previous U.S. presidents had contributed to the evolution of bilateral relations. George W. Bush was particularly popular with the Indian establishment because of how much he personally invested in the relationship. Barack Obama grew the ties in other ways, though New Delhi believed he wasted his first term kowtowing to China. Nonetheless, the expectation was that any U.S. president would consider India an important partner.

During his campaign, Mr. Trump took a positive view of India, but for reasons only tangentially strategic. His real estate franchise had recently arrived in India and Trump Towers were coming up in four Indian cities. A few wealthy Indian-Americans had contributed to his campaign and persuaded the candidate to issue a video praising Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

A big picture was hard to discern in Mr. Trump’s foreign policy statements, let alone where India fit into his worldview.

Finally, a group of right-wing advisors to Mr. Trump claimed that the Indian leader’s 2014 election win was a harbinger of their candidate’s victory. One of those advisors, Steve Bannon, said the “center-right revolt is really a global revolt. … I think you’ve already seen it in India.” In New Delhi’s view, a big picture was hard to discern in the candidate’s foreign policy statements, let alone where India fit into his worldview.

First year

India was largely reassured by President Trump’s first staffing choices. Figures such as National Security Advisor H. R. McMaster, Defense Secretary James Mattis and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson were part of the Washington establishment. India also knew there was bipartisan support for a stronger Indo-U.S. relationship inside the Beltway.

Mr. Trump’s early declarations of affection for Russia, his administration’s withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital did not impinge on core Indian interests. His denunciation of the nuclear deal with Iran made India uncomfortable, but New Delhi accepted it was a policy the U.S. Republicans had never endorsed.

India was more concerned about the president’s strong isolationist streak, specifically, his stated intention to withdraw U.S. troops from Afghanistan and, more generally, his seemingly erratic support for his country’s alliances in Asia. Mr. Trump’s stray remarks about Kashmir mediation were eventually dismissed as an attempt to gain international acclaim rather than policy considerations.

Facts & figures

Growing trade partnership

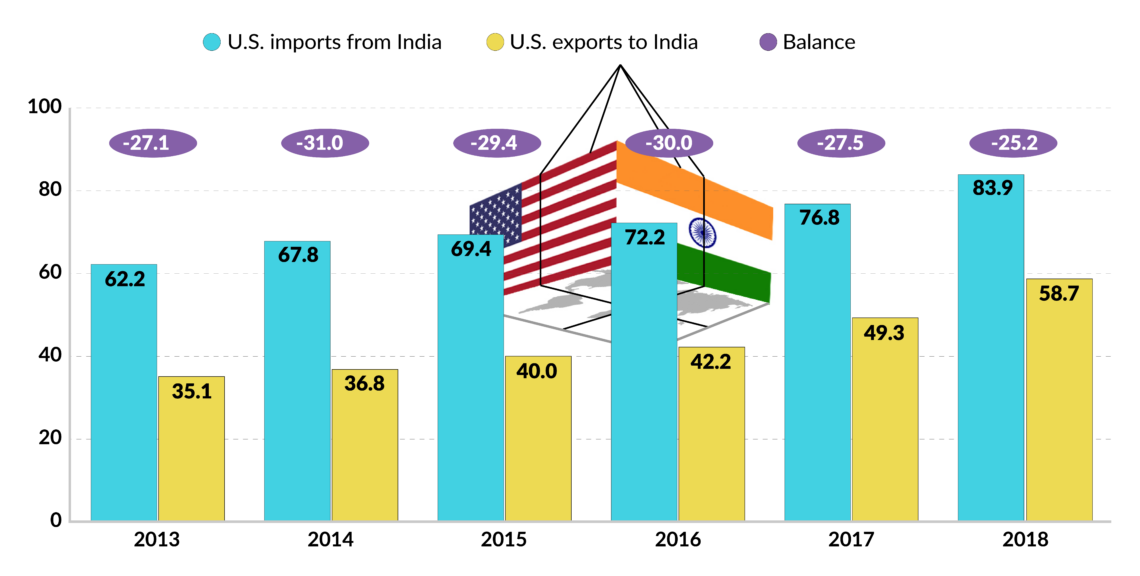

U.S. goods and services trade with India ($ billions)

On the other hand, New Delhi was truly unhappy over President Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris climate agreement. India rallied with the European Union and Japan to preserve the treaty. It was also displeased with the U.S. restrictions on skilled-worker and student visas, which are popular with Indians.

India managed the relationship on two levels. One was to work with the establishment to continue to push the strategic relationship. The importance of India was embodied in the U.S. National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy, issued in early 2018. The other tack was to leverage Mr. Trump’s apparently genuine liking for Prime Minister Modi and massage the former’s considerable ego.

At his first summit meeting with President Trump, Mr. Modi invited Ivanka Trump to be the most important guest of an international conference in India. The prime minister has continued with such tactics: he shared a podium with Mr. Trump at a political rally in Texas in September 2019, reckoning that his ability to attract 60,000 supporters on American soil would impress the U.S. president.

Second year and onward

Tying relations to multiple moorings held India in good stead as the Trump administration became more ideological in its second year. The new lineup of John Bolton, Mike Pompeo and, later, Mark Esper, proved as enthusiastic about India as their predecessors. India won points by quickly reducing its oil imports from Iran in accordance with U.S. sanctions and joined administration officials in thwarting President Trump’s attempts to pull out of Afghanistan. The U.S. Congress helped dilute many of the anti-immigrant policies that affected Indians.

The Modi government has been most pleased with President Trump’s tough stance toward China.

India was less successful when it came to deflecting the U.S. president’s strong feelings about trade. Though India had a trade surplus with the U.S. of only about $26 billion, Mr. Trump repeatedly criticized the country for its high tariffs on manufactured and agricultural goods. The charges emanating from the Oval Office sometimes baffled officials of both governments. The U.S. president often complained about how few Harley-Davidson motorcycles India imported. The U.S. firm itself explained that imports were low because it had factories in India.

In the end, Prime Minister Modi failed to provide clear guidance to his own negotiators and two years of trade talks fared so poorly that the U.S. revoked preferential market access for Indian goods in June 2019. The two sides are now engaged in negotiations to settle several trade issues before the 2020 elections dominate the U.S. president’s attention.

The Modi government has been most pleased with President Trump’s tough stance toward China. India sees the rise of an assertive China as its primary strategic challenge. While Mr. Trump’s use of tariffs as a weapon of statecraft is questionable, the trade and technology conflict has helped put China on the back foot. India has been happy with this side of Donald Trump and has been prepared to forgive him for many things as a consequence. Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, reflecting on President Trump, said recently that this “was not at all the traditional American system at work. You actually got big, bold, decisive steps in a range of areas.”

It helped that India, which does not hold a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council and has been a reluctant player in the global trading system, was not as invested in the existing world order as the Western democracies. It took Mr. Trump’s attacks on the international system in stride, flinching at only some of his tactics.

When the Indian media criticized President Trump, officials in New Delhi said, ‘Analyze him, don’t demonize him’.

India has never been a formal ally of the U.S. and is thus unaffected by the president’s complaints about the costs of maintaining overseas alliances. When the Indian media criticized President Trump, officials in New Delhi liked to tell them, “Analyze him, don’t demonize him.”

Scenarios

The primary variable is whether Donald Trump will be elected to a second term as president. If he returns, the expectation is that his current foreign policy will continue. On the plus side, from India’s perspective, he will resume his confrontational stance toward China. On the minus side, he will push forward with withdrawing from Afghanistan and reducing the U.S.’s overseas military commitments. It will also mean protectionism will be embedded in U.S. policy, which is why Prime Minister Modi has made it a policy priority to complete a trade deal with the U.S., no matter how small, by early next year.

India will remain a favored nation in that the establishment and, more often than not, the White House will be supportive of the relationship. But during a second term, New Delhi will be wary of investing in relations under a U.S. president whose understanding of strategy is tenuous. If the Democrats control the Congress and Donald Trump the White House, India could be reluctant to move the relationship forward, potentially damaging ties.

Prime Minister Modi will have another set of problems if the Democrats capture the presidency and strengthen their position in the U.S. Congress. The Indian prime minister is associated with the Trump presidency in the mind of the American left and a left-of-center U.S. administration will likely have a testy relationship with New Delhi over human rights in Kashmir and Mr. Modi’s religious-nationalist agenda.