India readies to face Trump’s trade ire

As the U.S.-China trade dispute drags on, Washington is gearing up to turn the screws on another trade partner: India. Though the countries are allies, U.S. officials chafe at India’s protectionist policies.

In a nutshell

- The U.S. has several grievances about India’s protectionist trade measures

- India has had difficulty addressing them during an election campaign

- The next Indian government will want to solve the dispute quickly

- Changing its stance on free trade could benefit India in general

India is bracing for a wide-ranging trade skirmish with the United States in the next few months. In March, the office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) announced it would withdraw India’s privileges under the generalized system of preferences (GSP), a tariff concession granted to developing countries. The administration of U.S. President Donald Trump has indicated that it will act after the new Indian government is sworn in on May 30. India, trying to avoid an escalatory tariff war, has remained passive. Officials hope to revive earlier bilateral attempts to negotiate a package of mutual trade concessions, probably sometime in June.

Medical equipment and motorcycles

The two countries sparred on trade issues through the latter half of last year. The USTR’s immediate grievance against India was the latter’s imposition of price controls on medical devices nearly two years ago. There were also India’s high tariffs on a handful of electronic imports that the U.S. saw as a violation, at least in spirit, of the World Trade Organization’s Information Technology Agreement. A set of big-picture issues about India’s digital economic policies, including the regulation of foreign-owned e-commerce firms and data localization, has added to the U.S.’s irritation, but is not on the official agenda.

On top of this, President Trump has his personal pet peeves. He is unhappy with India’s trade surplus with the U.S., a relatively modest $24.2 billion in 2018. More idiosyncratic is his criticism of Indian tariffs on Harley-Davidson motorcycles. President Trump first cited India’s tariffs on Harleys in 2017. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi personally informed the president that India had reduced the tariff from 75 to 50 percent early the following year. Mr. Trump publicly dismissed the move, even while calling Prime Minister Modi “a great gentleman,” and demanded India cut the tariff to zero.

President Trump continues to raise the issue of the tariffs on Harleys, while diplomats wring their hands over its triviality.

Indian and U.S. officials privately say this was a missed opportunity to get the India trade file off the president’s desk and back into the more staid hands of the bureaucracy. “Politically, it would have made sense to take the tariff to zero or done nothing,” admitted one Indian official. A U.S. diplomat noted that since Harley-Davidson already manufactures in India, President Trump’s complaint applied only to 1000cc engine motorcycles – of which India imported just over 80 in 2018. The U.S. president continues to raise the issue of the tariffs on Harleys in public, even as diplomats wring their hands that such a trivial issue has become a White House obsession.

Trump’s agenda

Yet there is a method to President Trump’s trade madness. After coming close to securing a trade deal with Beijing, he has begun to tighten the screws on other countries. The European Union tops the list. Taking up cudgels against unfair trade practices, Mr. Trump believes, is popular with his working-class voter base.

The office of the USTR has had long-standing grouses about India’s broadly protectionist policies against goods and farm products and aspects of its intellectual property rights regime. Current U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer has merged his office’s agenda with President Trump’s personal concerns. When Indian officials tried to revisit the Harley-Davidson issue, they found the USTR had combined the agenda with a much larger U.S. push against a whole panoply of India’s trade and investment policies.

Like other countries, India has had to adjust to President Trump’s approach. He sees no contradiction in wooing a country for strategic reasons, while at the same time giving no quarter on the trade front. That Mr. Trump personally likes Mr. Modi makes no difference. Nonetheless, many parts of the Washington establishment, like the Pentagon and the U.S. Congress, are strongly committed to the U.S.-India relationship and have lobbied hard to limit the damage on the trade front. “We’ve bent over backwards for you,” senior U.S. diplomats have insisted.

Facts & figures

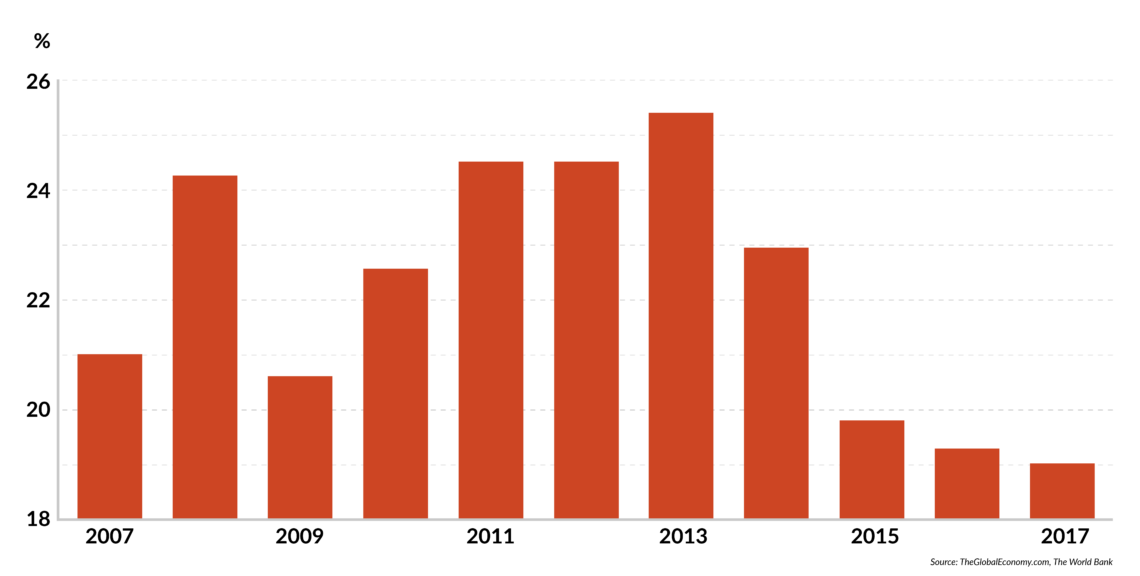

India: Exports (goods and services) as a percentage of GDP

The two sides tried twice to negotiate what Indian Commerce Minister Suresh Prabhu called a “trade package” of mutual concessions. After negotiations in the fall of last year and January this year, the two agreed to a formula, based on the trade margin, for medical device prices and tariff cuts on six electronic products. “We conceded 90 percent of the U.S.’s demands,” said an Indian diplomat. But negotiations fell apart.

Washington claims New Delhi’s written offer differed wildly from what had been verbally negotiated. Indian officials claim the USTR raised its demands. India requested additional time because of its general elections, but Mr. Lighthizer had lost patience and went ahead and announced the revocation of GSP privileges. By mid-March, Indian commerce ministry officials were resigned to losing the $190 million worth of tariff concessions.

Scenarios

Sorting out this trade imbroglio will be among the next Indian government’s foreign policy priorities. The last round of negotiations will provide the template for the negotiations. Unlike in the past, however, the Indian prime minister’s office will probably get directly involved in the talks rather than let its commerce ministry take the lead role. Insiders say this will be necessary to bring other ministries in line with the Indian stance. The assumption is that given their rapidly converging strategic interests, neither the U.S. nor India want to escalate the trade dispute too far.

The worst-case scenario is one where the negotiations drag on throughout the rest of this year. In that case, the possibility of President Trump ordering more penalties against India and New Delhi retaliating becomes much more likely. It seems probable that a weaker government will come out of the Indian elections, while the U.S. will be knee-deep in its presidential campaign. Bilateral trade remains relatively small, but the impact on the broader Indo-U.S. relationship could be considerable.

The next Indian government also needs to take a much harder look at its attitude toward trade. India’s exports fell from about 23 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in fiscal 2014 to about 19 percent in fiscal 2017, and the figure is expected to fall further. The Modi government’s negative attitude to free trade agreements has meant the loss of overseas markets to competing nations – one reason car exports fell 10 percent in fiscal year 2018-19. While there has been a recent uptick in India’s export figures – ironically, U.S.-India trade rose a healthy 12 percent in 2018 – trade contributes remarkably little to the Indian growth story.

India has also failed to consider the impact of larger global trends in trade negotiations. The standards incorporated in the new North American Free Trade Agreement would mean the end of all privileges for developing countries, free cross-border movement of data and much tighter intellectual property rights. New Delhi continues to put all of its trade policy eggs in the WTO basket, even while the main trading nations are laying out an agenda that is increasingly outside that body’s charter.

For example, India’s commerce ministry has baffled many Indian economists by staying out of informal WTO talks on setting global e-commerce rules. There seems to be a recognition that something is amiss. In one of his last acts before the elections, Prime Minister Modi set up a task force led by a prominent free-market economist to take another look at India’s trade policies and see if there was a need for an overhaul.