As Indian agriculture expands, farmers and reform prospects suffer

India’s food output has nearly quadrupled over the past 50 years, but farm households – more than half the country’s population – are in some ways worse off. Rural distress is weighing on the country’s politics and eroding the government’s political base.

In a nutshell

- Indian farmers are languishing even as agricultural output continues to grow

- The country cannot match Asian tiger growth rates without reforming the farm sector

- Price volatility and debt are turning desperate farmers against the government

- So far, Prime Minister Modi has preferred palliative measures to structural reform

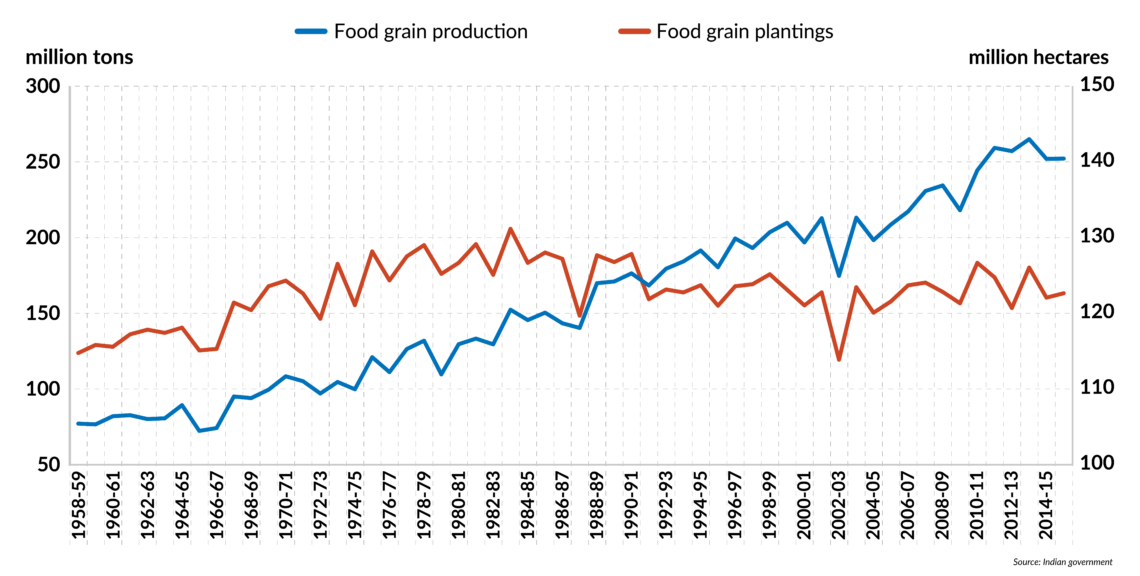

Over the past 50 years, India, often referred to as a basket case, has transformed itself into a breadbasket. There has been a fourfold increase in grain yields per hectare, leading to 3.7 times increase in output, to more than 250 million tons. Over the same period, the country’s population has expanded two and a half times. Today, India is a major agricultural producer and exporter. The success of Indian agriculture, however, has not reduced the distress of most Indian farmers.

Recent surveys have estimated that while over 50 percent of households are dependent on agriculture for a living, 67 percent of them operate less than one hectare, and another 18 percent possess just 1-2 hectares of land. Monthly income from farming is below the consumption and productive investment needs for about 69 percent of farmers. More than half of all farm households are in debt.

The challenges faced by India’s farmers are casting a dark shadow over the country’s wider political economy, and may explain the slow pace of economic reforms. As rural distress rises, the government incurs increasing political costs.

In early 2017, farmers across many major agricultural states took to the streets, seeking fair prices for produce and debt relief. This was the first widespread social protest faced by Prime Minister Narendra Modi since he was elected with a big parliamentary majority in 2014. His Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has won a string of provincial elections over the past couple of years, and is now in power in 19 of India’s 35 states.

India’s relatively slow growth has been blamed on a ‘democracy tax’ that allegedly retards development.

Yet when provincial elections were held in Mr. Modi’s home state of Gujarat in December 2017, the BJP lost most of the rural constituencies, even as it eked out a narrow victory in one of India’s most urbanized provinces. This could bode ill for the ruling party in 2018, when some of the country’s most populous rural states will hold legislative elections.

‘Democracy tax’

Since economic liberalization began in 1991, India’s economic growth rate has slowly climbed. But the pace of economic transformation has been much slower than in Asia’s original tiger economies, including South Korea and Taiwan. While India and China were almost at the same level in terms of per capita income in the late 1970s, the gap between these two giant neighbors has become stark today. Chinese gross domestic product has ballooned to over $10 trillion, five times larger than India’s.

It is generally believed that India’s rather slow economic transition is due to its boisterous and fractious democratic process, which imposes a kind of “democracy tax” that allegedly retards development. The country’s unruly politics is held in contrast to the more orderly authoritarian regimes that oversaw economic transition in the Asian tigers, and does so in China today.

Facts & figures

Indian grain output and plantings, 1958-2016

Agriculture tied in red tape

Over the past 25 years, Indian economic reforms have mainly focused on liberalizing the nonfarm sectors of the economy, particularly industry. Agricultural reform has stayed on the back burner, despite high-flown rhetoric on the subject from practically every political party.

The domestic land market suffers from gross administrative restrictions and is therefore distorted, preventing farmers from consolidating and allocating land more efficiently. This restricts the entry of new capital and technology, trapping farmers in low productivity while limiting their ability to cash out and exit.

Low farm productivity is matched by gross underemployment in rural communities. Over 50 percent of India’s workforce continues to depend for its livelihood on agriculture, whose contribution to GDP has fallen to barely 15 percent. Lack of nonfarm economic opportunities, coupled with low levels of education and skills, have greatly slowed social mobility out of agricultural occupations.

Government intervention has created a highly inefficient trading network for farm goods.

Over the past decades, several laws aiming to restrict storage and trade in agriculture produce have been enacted to discourage speculation and protect consumers. This interventionist approach has created a highly inefficient trading network for farm goods, with very high levels of wastage and extreme volatility in the prices of many food commodities. The problem has been compounded by an ad hoc export control regime, which the government rhetorically invokes to please either farmers or consumers, depending on the situation and context.

Access to technology is also distorted by various subsidies and controls on farm inputs. For instance, the debate over genetically modified crops has become politicized, with farmers being pushed aside in favor of other social groups with no direct stake in agriculture.

Facts & figures

GMOs tied up in knots

In October 2017, the Indian government deferred an earlier decision to approve genetically modified (GM) mustard and rapeseed. This is the second time the central government has changed its mind on GM crops. In 2010, going against a recommendation by its own expert committee, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s government had placed a moratorium on GM brinjal (or eggplant).

The GM mustard has been developed by a team of Indian scientists using two genes that change mustard into a self-pollinating plant. This would enable hybridization, allowing the development of higher-yielding strains than the native parental cultivars.

India has a checkered relationship with genetically modified crops. In the mid-1990s, the debate was triggered by Bt cotton, which produced a natural insecticide allowing the plants to better protect themselves against bollworm attack and reducing the need for chemical pesticides. While policymakers dithered, farmers in some parts of the country began using an unauthorized variety of Bt cotton in 2000-01. Its success galvanized cotton growers, and the government was virtually forced to approve the release of the first GM crop in 2002.

Today, 95 percent of cotton grown in India is GM, while annual production has almost tripled to 37 million bales, from 14 million in 2001. GM cotton has been so successful that the government has introduced price controls on seed packets.

However, the local company that pioneered Bt cotton in partnership with Monsanto – Mayco – has decided to cut back research on agricultural biotechnology. It recently announced that technology developed for use in India would be used to release GM brinjal in Bangladesh instead.

Indian farmers are paying a heavy price for such policies. Government restrictions and bans have spurred an illicit trade in pirated and spurious GM seeds. Apart from Monsanto’s Roundup Ready Cotton (resistant to the company’s glyphosate herbicide), it is reported that GM corn and soybeans are being sold on the gray market. Brinjal from Bangladesh is also likely to find its way across the border.

State of Indian agriculture

Today, India is among the world’s top producers in many crop categories. Yet farm incomes remain low. The average income of farm workers was only 34 percent of their urban peers in the 1980s, then fell to less than a fourth in the 1990s. Rural incomes recovered somewhat in the 2000s, only to deteriorate again over the past five years.

Among farm households in 2016:

- 53.4 percent were below the poverty line

- Only 47 percent of their income was derived from farming

- Monthly median incomes were just 1,600 rupees ($25)

Given such constraints, investment in agriculture has been declining and productivity is suffering. According to surveys, 40 percent of farmers want to quit, and 70 percent do not want their children to remain in agriculture.

As Dr. Arvind Subramanian, the government’s chief economic adviser, acknowledged: “The truth is, it simply does not pay to be a farmer in India.”

Political dimension

What has been overlooked, both inside and outside India, is that unless there are fundamental changes in the farm sector that bring tangible benefits to large sections of the rural population, Prime Minister Modi’s government will have a hard time sustaining the broad-based support necessary to push through its wider reform program. Without this social base, neither democratic or authoritarian governments, no matter how well-intentioned, can expect to radically improve economic performance and transform the national outlook within the span of a decade or two.

It is no coincidence that every country that made the transition from poverty to wealth over the past 60 years, especially the Asian tigers, began by reforming agriculture.

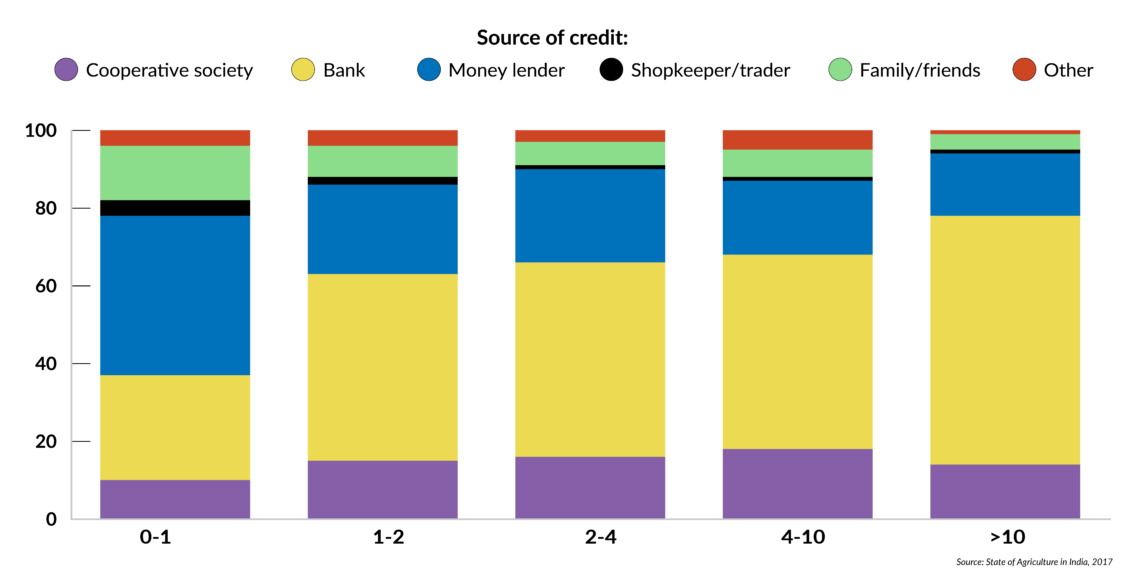

Facts & figures

Landholdings and credit sources, 2013

Size of farm (hectare)

Symptom 1: debt

Campaigning for last year’s provincial elections in Uttar Pradesh, India’s largest and most populous state, Prime Minister Modi promised to waive outstanding loans to farmers. Following the election, which his party won, other states began announcing various debt forgiveness programs for farm loans.

If all of India’s 29 state governments follow suit, these farm loan waivers could reach the equivalent of 2 percent of India’s GDP by 2019, according to June 2017 estimate by Bank of America Merrill Lynch. Others have estimated the total to be even higher, at up to 2.6 percent of GDP.

Loan waivers have been popular with India’s political class across the political spectrum – perhaps because they help shift the focus from the deep-seated problems on the ground.

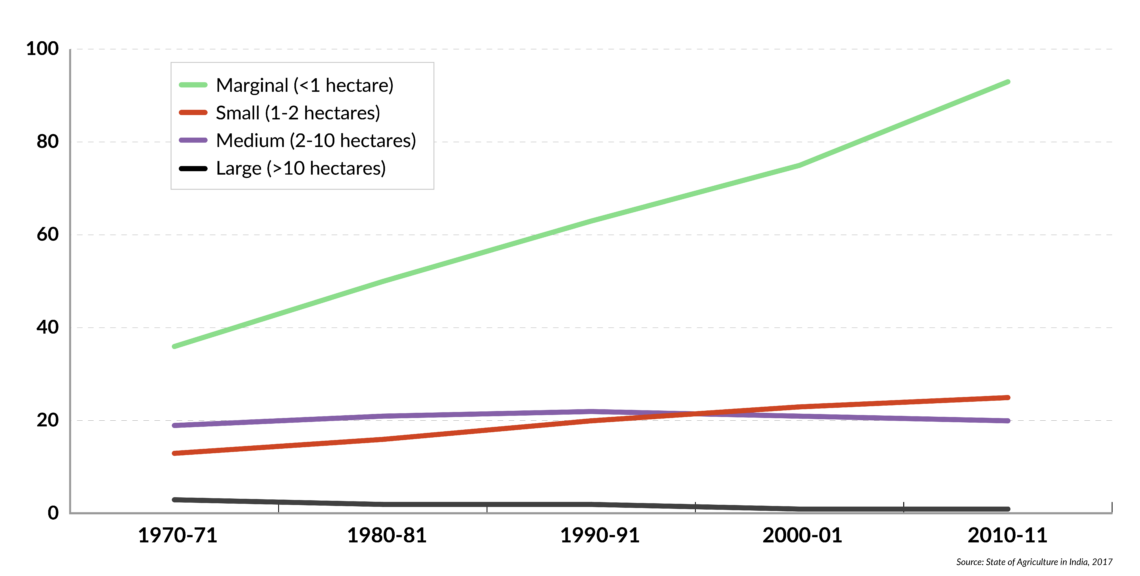

Symptom 2: landholdings

The average landholding of Indian farm households has continuously decreased from an average of 1.84 hectares in 1980-81 to 1.15 hectares in 2010-11 – a decline of 37 percent. Over this period, the total area of land under cultivation has stabilized at about 140 million hectares. The National Sample Survey Office estimated in 2013 that over 80 percent of rural households have marginal landholdings of less than one hectare, with just 7 percent owning more than 2 hectares.

Facts & figures

Indian farms by size

(millions)

The poor state of land records makes it very difficult to differentiate between de jure ownership, with proper documentation, and de facto possession. While well over 80 percent of Indians own land or property of some kind, much of these assets are frozen with little prospect of being monetized due to the lack of a functioning rural real estate market. Barely 5 percent of all loans in rural and urban areas are secured by mortgages on immovable property.

Since ownership of farmland is legally restricted to those who till the soil, anyone who wants to give up farming will have a difficult time finding buyers – especially since there are also ceilings on the amount of land farmers can legally own. In any case, most are too financially stressed to consider expanding their holdings. Nonfarmers must secure a series of special permits to buy farmland.

Symptom 3: missing (trade) links

While secure land and property rights are necessary for agriculture to develop, they are not sufficient. In China, all land is owned by the state, and the average farm size today is half a hectare – smaller than India’s. But China’s journey with economic reforms began in the early 1980s, with agriculture. The large state-owned farms were broken up, and rural families were given long-term leases and encouraged to grow their own crops. The subsequent phenomenal growth of agriculture, trade and food processing have significantly contributed to reducing rural poverty.

Despite many initiatives, barely 3 percent of Indian farm produce is processed.

Today, China’s farm sector accounts for only about 10 percent of GDP, while employing about a quarter of the labor force. However, that still puts China’s agricultural GDP at approximately $1 trillion in a $10 trillion-plus economy. In addition, food processing contributes another $2 trillion to the economy, which puts the combined share of the agricultural and food sectors at roughly 30 percent of total output.

In the late 1980s, India sought to promote food processing as a way of boosting farm income and lowering wastage. Despite good intentions and many initiatives, barely 3 percent of Indian farm produce is processed today. In 2017, the government announced with much fanfare another effort to encourage food processing, allowing foreign investors to hold 100 percent stakes in food manufacturing and trading ventures.

Facts & figures

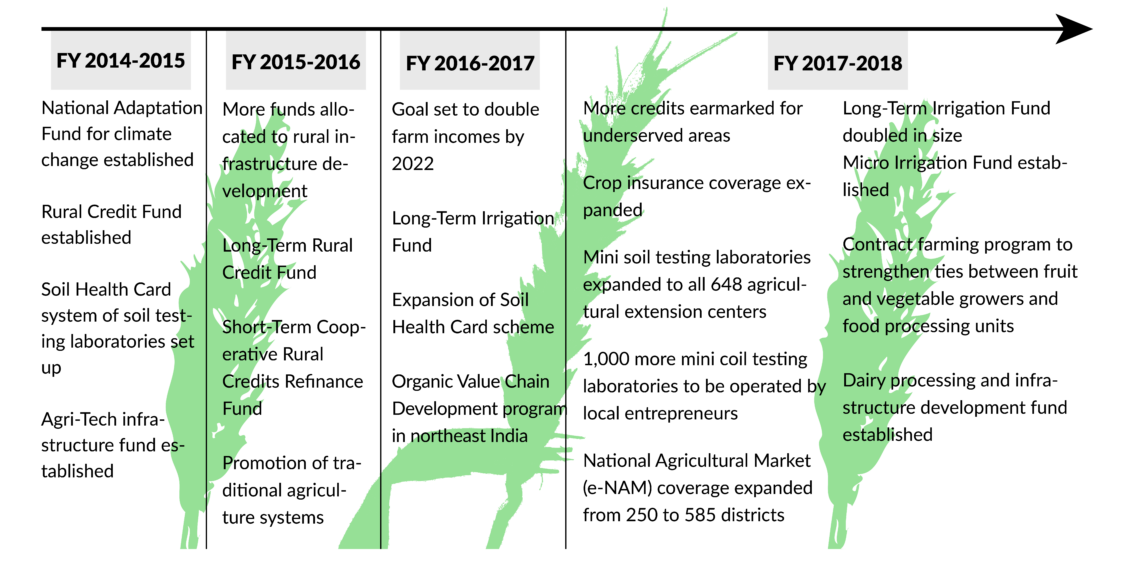

Government initiatives to boost agriculture

Government Initiatives

Every political party in India eulogizes the farmer. Yet every government has tied up the farmer in red tape. Successive governments have sought to juggle two conflicting priorities when it comes to regulating the sector. The first is to boost farm incomes by raising the minimum support prices (MSP) for major crops. The second is to keep food prices low enough to satisfy urban consumers. In this tussle, the farmers have mostly lost out to urban dwellers. The terms of trade have been mostly unfavorable to agriculture over the past 70 years, except for a brief interlude in the 2000s. But in recent years, conditions for farmers have again turned negative.

Following in the steps of its predecessors, the Modi government has launched its own high-profile initiatives for agriculture. In 2016, the prime minister announced the goal of doubling farmers’ income. But almost every new program has expanded the scope of government action, increased spending and narrowed the scope of farmers and traders to find their place in an open market.

Indian farmers have coped with the vagaries of nature better than the hazards of navigating through the maze of government policies.

Facts & figures

Pulses and prices

Pulses are a key source of protein in India, where vegetarians make up much of the population. Pulse crops cover one-fifth of the country’s total sown area. In the past few years, retail prices have been extremely volatile, fluctuating by as much as 500 percent. Following scanty rainfall in 2014 and 2015, prices rose sharply, and the government lifted import barriers to protect consumers. In 2016, after a good monsoon, farmers planted more pulses, only to see prices crash on a market glut. The government began emergency purchases to support farmers, yet only 60 percent of the crop was sold at the prescribed minimum price. Now the authorities have accumulated several million tons of pulses. Yet without proper storage and viable distribution channels, this intervention has done little to curb price volatility.

This year, the government has re-imposed import restrictions on some pulses, along with import duties ranging from 10 to 50 percent. Even so, prices have remained low and for some varieties had virtually collapsed by the end of 2017.

Ad hoc policy responses of this kind have created uncertainty among India’s farmers and international trading partners. Without a futures market, agricultural producers can only be guided by expectations based on prices of the previous year. Given the experience of 2016-17, it is quite likely that farmers will plant less acreage in 2018. Canadian producers, an important source of Indian pulse imports, have already reduced their plantings. That suggests there could be another price spike in 2019.

This sort of situation repeats itself someplace in India virtually every year. In the summer of 2017, for example, farmers in Maharashtra dumped their tomato harvest in the streets to protest collapsing prices. In the autumn, farmers in Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat were upset about low soybean prices. In January 2018, potato farmers in Uttar Pradesh destroyed their crops in the field and dumped unwanted produce in front of the offices and residences of senior officials. Their farm gate price had fallen to barely Rs 0.20 per kilogram (a fraction of one U.S. cent), while just a few hundred kilometers away, in Delhi, the retail price of potatoes was hovering around Rs 15-20 (about 30 U.S. cents).

Conclusion

China’s emergence as the world’s factory is widely recognized. What is generally not realized is that it followed the earlier Asian tigers in first reforming the farm sector. This created the social capital needed to undertake a wider economic transformation, by demonstrating the benefits of reforms to the largest segment of the population in the 1980s – the farmers.

Even so, Chinese agriculture is not without its challenges. The sector is significantly undercapitalized, productivity remains modest and the workforce is rapidly aging.

Building the social support necessary to restructure the economy is impossible without farm reform.

Most of the issues pertaining to agricultural reforms listed above have been debated in India for years. But Prime Minister Modi’s propensity to grandstand, rather than to analyze the situation objectively, makes it quite unlikely that he would be willing or able to undertake meaningful reforms in agriculture.

India now finds itself in a Catch-22. In a country where the vast majority of the population is engaged in agriculture and the informal economy, building the social support necessary to restructure the economy is impossible without farm reform. Yet unless the broader economic reforms come early in the transition, there will be no nonfarm jobs to absorb the 80-100 million surplus rural laborers who must move off the land and adapt to urban life.

Scenarios

Those interested in India’s economic future would do well to keep a close watch on proposed changes in agriculture and rural areas. Reforms in the nonfarm sector alone cannot unlock the Indian economy’s true potential.

India’s growth rate has been slowing since 2015. Its economy is still struggling to overcome the aftereffects of the poorly conceived demonetization and badly prepared introduction of a national Goods and Service Tax (GST). This cramps the government’s ability to maneuver in the fiscal space. After the relatively good monsoon in 2017, and with favorable weather this year, this could theoretically create a window of opportunity to initiate fundamental reforms in the rural sector – releasing the entrepreneurial energy of India’s farmers and traders by getting the heavy hand of the state off their backs. Unfortunately, the probability of such a scenario playing out does not seem very bright at present.

The political calendar for the next 12-18 months also militates against any radical reforms in agriculture. The shadow of rural distress that fell over the Gujarat elections is likely to cloud the political horizon for elections in six more states in 2018. Many of these areas are significantly more rural than Gujarat.

Over the past three years, Mr. Modi has revealed his basic inclination to tackle economic challenges by throwing public money at them. He seems to see in the present agricultural distress a political opportunity to score points by leveraging state largesse. In that case, we can expect more loan waivers, price support, trade restrictions and welfare schemes aimed at rural areas. But at best, that approach will only push aside the underlying problems for a time.