Can India make its own weapons?

India seeks to make its own weapons. If the West wants to end India’s dependence on Russian arms, it will have to help New Delhi in these efforts.

In a nutshell

- The West has an opportunity to wean India away from Russia

- Reforms to boost domestic capacity face resistance, funding woes

- The war in Ukraine may accelerate changes in defense sector

India has been carrying out major internal reforms of its defense sector over the past several years, with the overall goal of broadening its small and inefficient domestic arms manufacturing base. This process has received a new sense of urgency following the Russian invasion of Ukraine and India’s continuing dependence on Russian weapons.

The reforms are moving slowly in part because their sheer depth and breadth have meant there is considerable resistance from various interest groups. The other constraint is funding, as the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi has kept a tight leash on defense spending.

One recent success of the reforms, however, is the signing of a $375 million deal to sell cruise missiles to the Philippines, the first-ever major export of offensive arms by India.

India’s defense issues

With nearly 1.5 million men and women in the armed forces, India has the second-largest military in the world. It is also one of the largest arms importers in the world. India’s share of global arms imports is over 10 percent, double the figure for China, though Beijing has a much larger defense budget. The reason: India has struggled to make the most rudimentary military equipment, such as rifles, let alone tanks and airplanes.

A cluster of state-owned defense firms with powerful unions and links to the defense bureaucracy are quite happy to assemble kits bought from overseas. The armed services are only concerned about the quality of the weapons they get and not where they are made. The political class lacked the bandwidth to focus on the issue and, if repeated arms scandals are an indication, saw rent-seeking opportunities in opaque foreign military contracts.

India has struggled to make the most rudimentary military equipment, such as rifles, let alone tanks and airplanes.

While the Indian establishment recognized both the economic and strategic costs of such a situation, they struggled to find a solution. Mr. Modi is the latest Indian leader to try and fight through this policy thicket. The administration has laid out a clear goal: ram through reforms that would allow for the growth of private-sector, homegrown arms makers. Over the past seven years, New Delhi has constituted half a dozen different committees to come up with ideas. Many withered on the vine. One committee faced so much opposition that it was disbanded without ever meeting.

Reforming path

However, changes are already evident. The most important has been a new, streamlined procurement structure that encourages Indian firms to bid for defense contracts and foreign defense firms to seek Indian partners. One manufacturing category, Buy Global Make in India, allows Indian firms to contract foreign technology but make the systems on Indian soil and is widely seen as a success leading to the growth of new private Indian defense firms like Tonbo Imaging and Solar Industries.

The government also privatized a sprawling but inefficient maker of military supplies, the Ordnance Factory Board. Its most ambitious plan, still to be realized, is a strategic partnerships program under which consortia of Indian and foreign firms are supposed to join hands to build major platforms like submarines and fighter jets.

This has gone hand in hand with major structural reforms of the military, including creating a chief of defense staff, an officer in overall charge of the three services, and more slowly the integration of the forces’ multiple commands. The Modi government, despite its right-wing credentials, has ensured defense spending as a percentage of GDP is now at one of its lowest levels since 1962. The philosophy behind this: the defense establishment must be financially and politically squeezed if it is to carry out the changes that will ensure it gets more bang for its buck. New Delhi says it has cut defense imports by 10 percentage points between 2018 and 2020 and it has scored genuine successes in manufacturing some classes of weapons, notably artillery and missiles.

Russians still coming

Where India continues to struggle is in crucial offensive platforms, notably fighters and warships. For many legacy issues, as well as reasons of cost, India has developed a cut-and-paste practice for many of its arms under which it brings together platforms and subsystems from different countries.

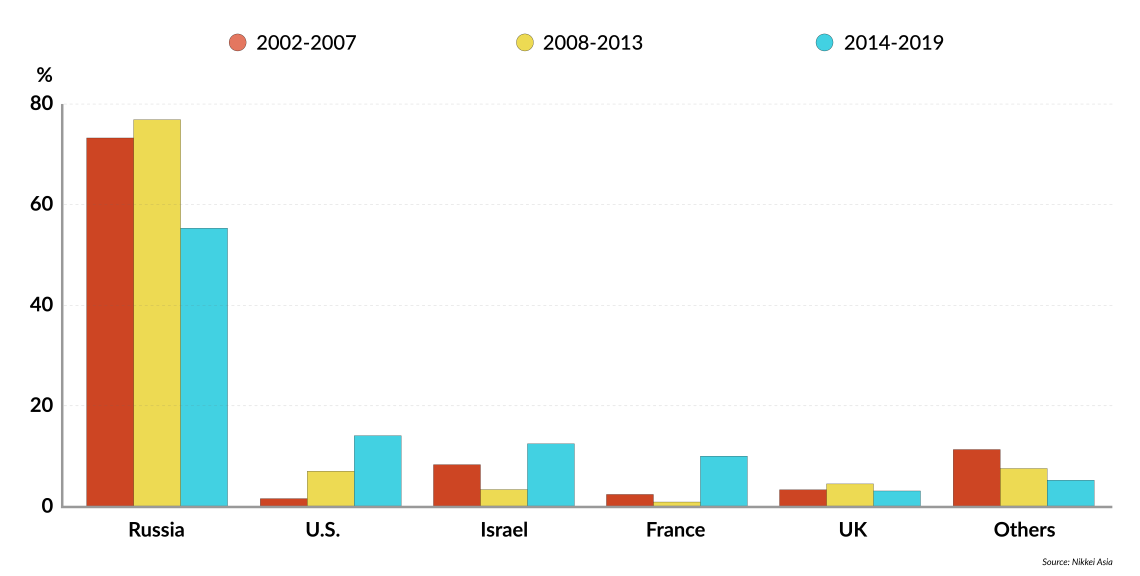

The main beneficiary has been Russia, the provider of nearly 70 percent of India’s weapons systems by value, of which the most important are fighters. While Russia also provides similar Sukhoi fighters to China, India’s main strategic adversary, India enhances its fighters with electronics and missiles from third countries of which the most important is Israel. Critics argue this is a suboptimal practice in today’s age of networked warfare. India’s response is that this is a major money-saver and enough to take on its adversaries.

Nonetheless, geopolitics and technology mean India has been slowly shifting away from Russia. New Indian purchases from Russia peaked in 2015 and have been declining since. But there are few arms sources who have been as dependable as Russia – prepared to ship off tons of weapons overnight, steadfastly neutral even when India is at odds with China, and willing to provide sensitive submarine technology for India’s nuclear deterrence.

Yet India has been diversifying. One reason has been the limits of Russian technology in areas like drones, transport aircraft and fifth-generation fighters. Another has been India’s strategic shift toward the United States and a parallel movement in Russia’s relations with China. New Delhi’s policy has been to ensure any retreat from Moscow is done in an orderly fashion.

Facts & figures

India’s arms suppliers

BrahMos and all that

The willingness of Russia and Israel to help India build its domestic weapons-making capacity manifested itself when New Delhi announced the sale in January of three batteries of BrahMos cruise missiles to the Philippines. The supersonic missile allows the Philippines to strike Chinese warships in parts of the disputed South China Sea. The deal is the first sale of an offensive weapon by India, a country that historically lacked the ability or desire to sell weapons. The BrahMos is the result of a joint development project between India and Russia. The Indian version of the missile today is about 20 percent Russian, largely the scramjet. India has similar programs with Israel.

What seems likely is an overall strategic reevaluation by India of its relations with Russia.

So far, similar projects with the West have not taken off. The U.S. legally struggles to provide defense technology to a country that is not a treaty ally. France and Britain express similar legal constraints and resist India’s patchwork way of putting together a weapon. There has been some forward movement, especially with France, with India trying to negotiate the joint development program of a next-generation fighter. However, this still has many hurdles, with the price and access to jet engine technology the foremost points of difference.

Scenarios

The fairytale scenario would be to have the Western governments come together and offer arms agreements that would allow India to wean itself off Russian weapons. However, while U.S., British and French officials have aired such plans, they continue to be less than generous about supporting India’s domestic manufacturing goals. Their approaches seem uncoordinated and lack clear timelines which, in any case, would be stretched by New Delhi’s present financial difficulties. At best, India can only hope the Ukraine crisis will put some urgency behind the West’s defense technology cooperation plans.

What seems likely is an overall strategic reevaluation by India of its relations with Russia. Moscow has shown itself to be erratic and unstable, more a tin-pot dictatorship than a mature great power. India had already been unsettled by Russia’s support for a return of the Taliban to Afghanistan and its betrayal of historical ally Armenia in the latter’s struggles with Azerbaijan. The Ukraine war is the latest – even if most violent – act in a series of impulsive acts. If this reevaluation does take place, and France makes major concessions regarding key weapons systems like fighters and submarines, the India-Russia defense relationship would find little to hold it together. This is an organic development with a high percentage of happening, but likely to take a decade or more.

The best scenario for India would be the least likely: its Indian defense sector suddenly coming together in unexpected ways. While India has made strides in terms of armor and can make the hulls of its warships, it remains a laggard when it comes to fighter aircraft. If its medium-sized fighter project makes progress in the next several years, India would have achieved a degree of autonomy in basic weapons platforms that would have been deemed impossible a few years ago. This would mean foreign arms purchases would be restricted to niche technologies, something that would be transformational in terms of diluting the Russian dependency and making India a more proactive player in the international arena.