Indonesia’s foreign policy after the 2024 presidential elections

The Southeast Asian nation of 270 million people will soon elect a president to succeed Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, whose focus on economic growth has guided Indonesian foreign policy.

In a nutshell

- A three-way race will decide who replaces the popular 10-year incumbent president

- Indonesia, now ranked 16th among national economies, wants to be in the top five

- Changes in the nation’s foreign policy will reverberate throughout Southeast Asia

On February 14, Indonesia – the world’s fourth-most populous nation, third-largest democracy, biggest Muslim-majority country and a leading voice in Southeast Asia and the Global South – will hold a momentous election.

The winner of a three-candidate race will replace President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, the popular 10-year incumbent, whose second and last possible term ends this year. The winner will shape foreign policy for the archipelagic nation of over 270 million people. Since Jokowi’s tenure began in 2014, he has advanced a domestic-centered, economy-first foreign policy to develop Indonesia into one of the world’s top five economies by 2045. Now the nation ranks solidly in the top 20 – usually in 16th place – with a nominal gross domestic product of $1.3 trillion in 2022, according to the World Bank.

President’s foreign policy advances economic goals

To accomplish this ambitious goal, he has strengthened the country’s economic diplomacy, reinforced its status as a commodity giant through onshoring production within the nation and kickstarted big-ticket infrastructure projects. The largest of them is a multi-decade plan to build the new capital city of Nusantara, which would entail moving key functions away from the current capital of Jakarta.

Additionally, though Jokowi has shown little interest in geopolitics, his administration has continued to advance longtime foreign policy priorities in line with his vision, such as better managing the country’s maritime boundaries, enhancing its Indo-Pacific engagement and expanding its role as a global middle power. This was spotlighted during Indonesia’s chairmanship of the G20 in 2022 and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2023.

Jokowi has advanced his foreign policy agenda amid consistently sky-high popularity ratings across his two terms. Yet that agenda has not been without its limits. Indonesia has begun to see the risks from some of its big-ticket infrastructure projects, be it environmental abuses linked to Chinese nickel plants or the lack of foreign investment for the new capital city.

Rising geopolitical headwinds – including Covid-19, intensifying U.S.-China competition and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – have also made it more challenging for Indonesia to achieve the high-growth rates that Jokowi sought when he entered office. More generally, his narrower foreign policy focus has led to a sense of drift in Indonesia’s traditional leadership role within ASEAN relative to that of his predecessor, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, who was more active on the global stage.

As Indonesia heads into its presidential elections, the focus is shifting to what the country’s foreign policy will look like after Jokowi. The question here is less whether a stark departure will take place from Jokowi’s popular approach, and more about the extent of change we might see under the next administration.

Continuity and change in Indonesian foreign policy

Indonesian foreign policy to date has revolved around a mix of general continuity with some change. It treasures its ability to play a “free and active” role in world affairs, its identity as an archipelagic, maritime nation and its status as a leader in Southeast Asia. While foreign policy may not decide Indonesian elections, individual issues – be it the country’s maritime priorities or its approach to China – have featured in the campaign and brought out differences among the candidates.

Jokowi, for his part, has also been trying to minimize the extent of change by repeatedly and publicly urging his successor to continue his key policies, including the development of the new capital city. The exact mix of continuity and change is far from clear as of now.

Facts & figures

Why is Indonesia moving its capital?

Indonesia wants to relocate its capital by 2045 from congested Jakarta, home to nearly 11 million people with at least 30 million in its greater metropolitan area on the island of Java.

President Jokowi selected Nusantara, which means archipelago, as the site of the new capital. It is in East Kalimantan on the island of Borneo, more than 1,600 kilometers northeast of the current capital.

Jakarta is “congested, polluted, prone to earthquakes and rapidly sinking into the Java Sea,” according to the Associated Press. Indonesian officials say the new capital will be built on higher ground and will emphasize green energy and environmental sustainability. Its construction will take place on largely undeveloped land that is close to abundant natural resources, such as timber.

The completion date, timed for the 100th anniversary of the nation’s independence, is expected to cost tens of billions of dollars in public and private investment.

However, the decision is controversial and is already a contested political issue in campaigns for the February 2024 presidential election, with some politicians calling for the government to scrap or postpone the relocation plan, according to The Nation, a Thai newspaper.

The three candidates to replace Jokowi

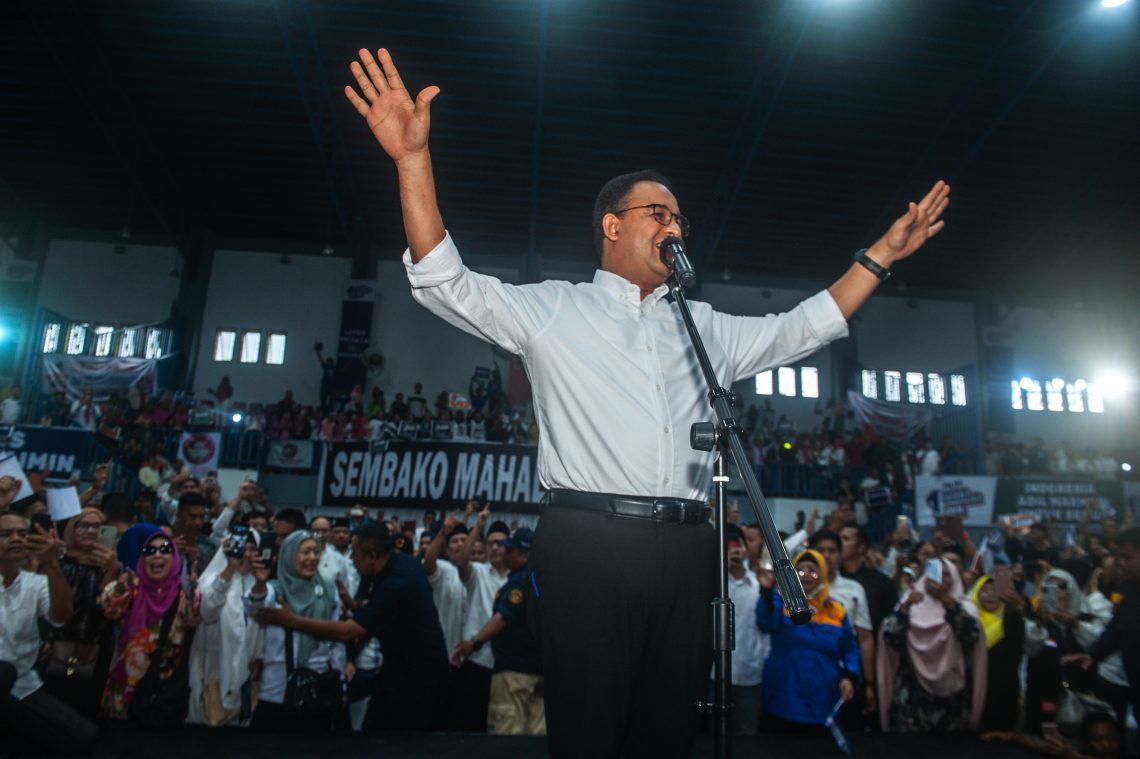

The 2024 election is a three-way race among ex-special forces commander and Jokowi’s two-time election opponent-turned-Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto; former Central Java Governor Ganjar Pranowo and former Jakarta Governor Anies Baswedan.

Of the three, Mr. Prabowo’s views on foreign policy are the best known given his past positions on areas like boosting Indonesia’s military capabilities and asserting its sovereignty against external enemies. Yet Mr. Prabowo has also been known to adapt his views, and his recent warming to Jokowi and selection of Jokowi’s eldest son, Gibran, as his running mate suggests that a focus on past positions alone may tell us little about his future actions.

Less is known about Messrs. Anies and Ganjar on this front. Both emphasized select areas in their manifestos submitted during campaign registration, including preventing domination from external powers and increasing weapons purchases. While this may point to areas of debate during the campaign, much of how foreign policy plays out during a new president’s term will depend on factors such as how they structure decision-making within their administration and the extent to which they take a personal role in this realm or delegate it to close advisors and relevant ministries.

Scenarios

Three scenarios are possible.

Most likely: Some moderate shifts in foreign policy

The first and most likely scenario is recalibration. Here, the next Indonesian president would not depart too far from Jokowi’s foreign policy vision but adjust the approach in some areas. This could include more scrutiny of Chinese investment into the country and a greater focus on drawing capital from other sources including Europe, Japan and the United States. This could also mean intensification in the policing of Indonesia’s boundaries, which could affect the country’s key relationships with neighbors such as Malaysia and Singapore.

In this scenario, Indonesia would still maintain its “free and active” foreign policy. But major powers would be dealing with a country where “freeness” would allow the country to speak out more actively on the international implications of developments concerning major powers, such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and even to play an active role in areas beyond narrow domestic interests, such as humanitarian assistance.

Indonesia’s neighbors would see a broader interpretation of its “active-ness” on the international stage, including not only regional issues like Myanmar or the South China Sea, but also being vocal at global fora, such as the annual United Nations General Assembly, and exerting influence in areas beyond the Indo-Pacific, such as intensifying Indonesia’s role in Africa as a bastion of the Global South and a future growth hub.

Possible: Continuation of Jokowi’s foreign policy

The second scenario is no significant change to the status quo. Although this scenario may have been seen as less likely even a year ago, it has become more likely over the past few months as Jokowi has intensified his efforts to ensure that as much of his legacy is preserved as possible.

This scenario would mean a continuation of Jokowi’s domestic-centered and economic-focused foreign policy. The bulk of the new administration’s attention would be on advancing select domestic and economic priorities as the lens through which Indonesia views its alignments regionally and globally. Indonesia’s neighbors, major powers and other regional and global partners would be working with a country primarily focused on advancing its own goal to become one of the world’s top five economies by 2045 and an active but non-aligned middle power securing its interests. Avenues for potential engagement would be heavily affected by economic nationalist policies, including the downstreaming of various sectors as the Indonesian government tries to ensure that the country captures more value from its raw materials within the country. The construction of the new capital would continue along with energy transition initiatives, the protection of overseas Indonesian workers and the enhancement of Indonesia’s tourism industry.

A priority would be placed on enhancing Indonesia’s sovereignty as an archipelagic state, including the curbing of illegal fishing, which involves several of the country’s neighbors, and developing maritime-related industries with the help of foreign partners. As we have seen in Jokowi’s two terms, aspects of foreign relations would be narrowly connected to select presidential priorities and may even be delegated to individual ministries and advisors. This in turn increases the possibility of bureaucratic infighting and mixed, incremental implementation of policies set at the top level, which will influence Indonesia’s ties with the world.

Least likely: A major departure from Jokowi’s years

The third and least likely scenario is the reinvention scenario, with a clearer departure from the general approach taken during the Jokowi years. Few expect major shifts like a return to the globalist vision of Mr. Yudhoyono, Jokowi’s predecessor who served from 2004-2014. But in one version of this scenario, Indonesia, under a more, proactive and values-based foreign policy, would play a more outsized international role on issues like the Israel-Palestine dispute that extend beyond its narrow interests and traditional platforms like ASEAN.

As this occurs, Indonesia could also tack closer to Western countries, including the U.S., as it seeks increasing capabilities to match its clearer intent on the world stage and counter China’s South China Sea actions.

Another, darker version of this scenario could see a more authoritarian and nativist foreign policy. Here, political leaders could merge populist impulses with authoritarianism and more exclusivist forms of Islam to shape a more ideological approach to foreign policy. Manifestations of this could include hostile approaches to foreign countries seen to not share Indonesia’s values, the dismantling of democratic institutions as well as a closer alignment with authoritarian countries like China and Russia as ties with Western countries fray.

This could also intensify economic nationalism in the name of protecting the interests of the Indonesian “street” at the expense of foreign companies. Though this scenario may seem quite unlikely now given what the candidates have said about their outlooks, it is one that nonetheless should not be dismissed out of hand.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.