Global competition for upstream oil and gas investment

The international energy community is usually divided on oil prices, since consumers like prices low and producers prefer them high. But one thing everyone agrees on is that the current environment of low oil prices is not encouraging investment, which could trigger an energy crisis down the road.

In a nutshell

- Upstream oil and gas investment tends to follow prices, as we saw in 2014-2016

- However, other variables are also key – including time lags and government policy

- State-led reforms have stimulated productive investments in some countries

The international energy community is usually divided about conditions on the oil market. When prices increase, consuming nations complain and producers rejoice. When prices fall, those feelings of happiness – or discontent – are reversed. The cycle goes on and it is never clear what would satisfy both parties.

Today, however, the international community seems united in one concern. Organizations representing consumers and producers are warning that an energy crisis is looming, because the current oil price environment does not sufficiently motivate investment.

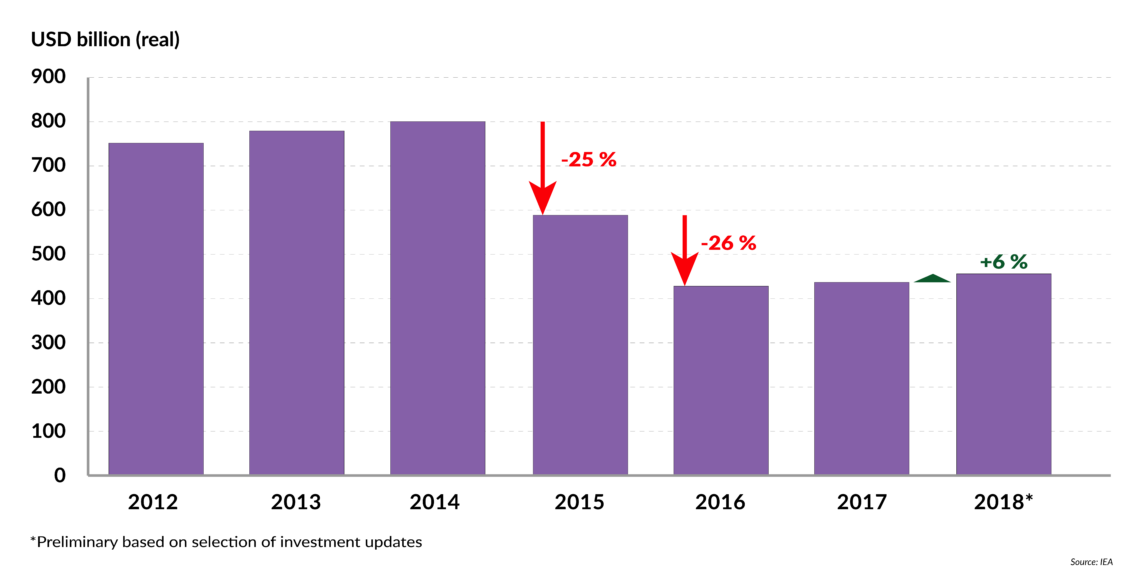

When the oil price collapsed by more than 50 percent between 2014 and 2016, investment – particularly in the upstream part of the business, focused on exploration and production – plunged as well. Many projects were canceled outright, while others were delayed indefinitely. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimates that global capital expenditures in the oil and gas industry fell by 44 percent over this period, to $434 billion in nominal terms, though it is unclear how the agency came up with these numbers.

Things have started to look brighter since, as oil prices have gradually recovered courtesy of OPEC and its allies led by Russia as well as the heightened geopolitical risks in the Middle East. The oil price has increased by about 34 percent since the deal to cut production by 1.8 million barrels a day (mb/d) was announced in December 2016. Investment stabilized in 2017 and is expected this year to show the first signs of renewed growth since the crisis.

Host government policy is another important driver of oil and gas investment.

For some, this is still a far cry from the levels seen only a few years ago. However, it must be remembered that oil and gas investments are complex decisions shaped by many factors, some of which either reinforce or counterbalance each other. The oil price has a direct impact on investment, since it affects the expectations about future returns. But it is not the only factor that can encourage or discourage investment. Host government policy is another important driver which in turn affects the cost of doing business.

Lower oil prices drive political acceptance and support of investment. In today’s climate, pro-investment policy reforms are more evident as countries compete harder for global capital. This may well provide the necessary boost to capital expenditures in the oil sector.

Trouble ahead

The International Energy Agency (IEA) which represents the interests of 30 OECD countries, predominantly oil consumers with a few net exporters, has been warning of a supply crunch due to low investment since the price collapse in 2014. In its “Oil 2018: Analysis and Forecasts to 2023,” the agency confirms that the oil market will be sufficiently supplied over the next five years. But after that, inadequate capital spending in the upstream sector will start to take its toll on the oil market, “storing up trouble,” in the IEA’s words.

In a remarkable act of solidarity, OPEC has made similar calls. The organization’s secretary general, Mohammad Sanusi Barkindo, warned that lack of investment is “sowing the seeds for [a] future energy crisis.” Assuming that supplies tighten and demand continues to grow, the world oil market would be headed for a significant increase in prices.

Only a few months ago, experts and senior industry figures were talking about “lower for longer.” Now, they seem to have executed a 180-degree turn, with some even predicting that the oil price could return to three digits. Even a cursory look at the past, however, shows that analysts rarely, if ever, get their oil price forecasts right.

Lead time

The oil price-investment-supply nexus is best understood in the context of conventional oil, which provides most of the world’s supply.

For a conventional oil project, it takes seven to 10 years to convert investment into production. In this respect, oil production today is the result of investment decisions taken about a decade ago. In the North Sea and the United States Gulf Coast region, for instance, oil production increased during the price slump of 2014-2016 because of investment decisions made during the preceding period of high prices. This explains why experts describe the conventional oil supply as inelastic: it is not responsive to price changes in the short term.

Facts & figures

Global oil & gas upstream capital spending, 2012-2018

Tight oil is different; the lead time from investment to production has shrunk to months and output is more visibly responsive to short-term changes in prices. However, tight oil represents a small fraction (around 6 percent) of world oil production.

Given the long lead time of conventional oil, one can understand present concerns about future supplies and the need for more upstream investment, not just to meet growing demand but to offset the natural decline in production from existing fields.

Investment drivers

The Saudi energy minister, Khalid Al-Falih, recently warned that the oil price recovery has not been enough to spur investment. His comment can be interpreted to mean that the oil price needs to rise further to boost investment, and/or that something else needs to be done.

When prospective investors decide whether to commit capital to an upstream project, they consider several variables. These include the chance of finding oil or gas; the potential size of the discoveries (which will dictate future production); oil prices; the cost structure; and the overall policy environment, which would include government regulations and fiscal terms.

These elements do not compose an a la carte menu from which the investor can choose freely. They must be taken as a whole; and their overall balance will determine whether the investment proposition is worthwhile or not. The policy environment, however, is a tool that governments can use to prompt a certain industry response.

Facts & figures

Upstream facts

- Each year the world needs to replace 3 million barrels a day (mb/d) of supply lost from mature fields while also meeting robust demand growth (IEA, 2018)

- The International Energy Outlook 2017 (IEO2017) anticipates oil and gas output will significantly increase as large, capital-intensive projects come online after 2025 to meet rising demand (Energy Information Administration, EIA, 2018)

- In 1938, Mexico became one of the world’s first countries to nationalize its oil industry

- On Nov. 30, 2016, OPEC announced a coordinated production cut of about 1.2 mb/d, limiting its production to about 32 mb/d. A week later, 10 non-OPEC members, led by Russia, also pledged to trim their combined output by an additional 600,000 b/d, bringing the total cuts to 1.8 mb/d, effective January 2017

- The Brazil pre-salt area is home to the Libra field, one of the largest offshore oil discoveries in the past decade

Policy prompts

In today’s climate of “scarce” capital, global competition to attract investment has intensified. From the Americas to Europe and the Middle East, Africa and Asia, governments have announced and implemented reforms designed to make their country a more attractive investment proposition than elsewhere. They are offering more acreage for companies to explore and holding more licensing rounds to optimize the chances of awarding contracts to a larger number of players. Some countries have trumpeted the success of these new measures in comparison with their neighbors.

Earlier this year, President Donald Trump decided to open almost all U.S. coastal waters to oil drilling. The executive order marked the single largest expansion of offshore oil and gas lease sale ever proposed by the federal government, giving oil companies access to vast areas for bidding. The move is part of the government’s “America First Offshore Strategy.” Additionally, the oil industry would benefit from the reduction in the corporate tax rate that was introduced last year.

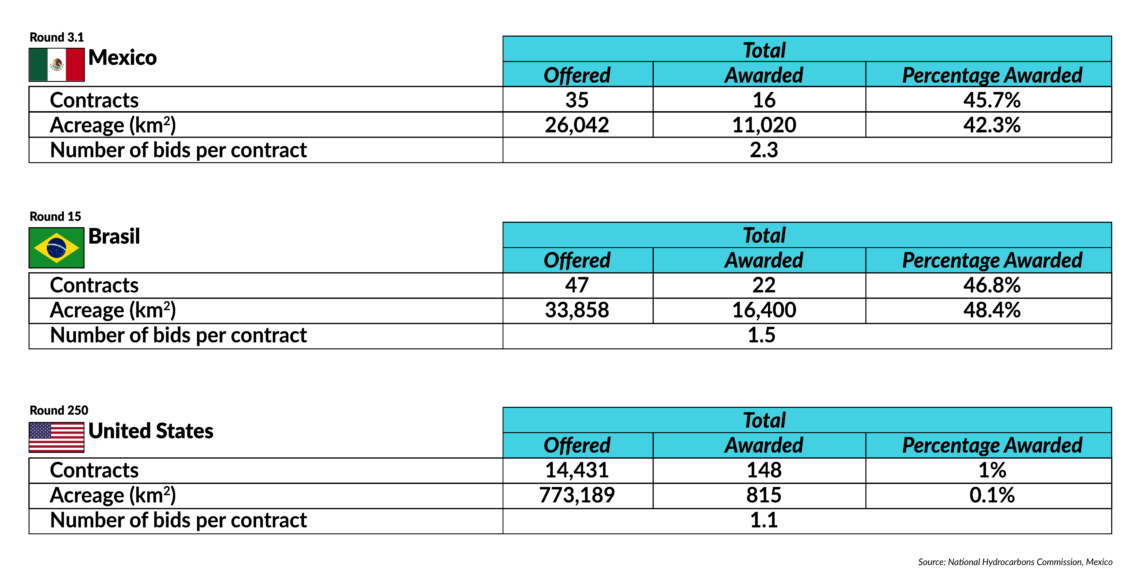

Mexico, for its part, after closing its upstream oil industry to foreign investment for 75 years, implemented energy reforms in 2013-2014 that ended the monopoly of its national oil company, Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex). Since December 2014, Mexico has organized an average of four licensing rounds yearly, attracting a variety of bidders, including international oil majors. The government was so proud of the results that its market regulator published a comparison of the bidding outcomes with those in Brazil and the U.S. For bidding Round 3.1 of 2018, Mexico awarded 45.7 percent of the offered contracts, similar to Brazil, but “with a very outstanding result” compared to the U.S., said the National Hydrocarbons Commission (CNH).

Facts & figures

Oil exploration license bidding, 2018

Brazil held no licensing rounds between 2008 and 2013. The decline in oil prices and a series of corruption scandals that hit its national oil company, Petrobras, and much of the country’s political elite had a negative impact on the whole industry. Hoping to reverse the decline in investment, Brazil introduced several reforms to alleviate the burden on investors – from extending license duration to reducing taxes and bureaucracy. For 2017-2019, Brazil planned nine rounds of bidding, and from the results so far, the new measures seem to be paying off. In the country’s 15th round, which took place in November 2017, companies bid aggressively and offered advance payments that exceeded Brazilian officials’ expectations.

Governments elsewhere are taking notice. In the United Kingdom’s licensing round held in 2017, new types of oil and gas licenses with flexible terms and durations were introduced. In North Africa, Algeria announced new plans this year for tax incentives to boost stalling investment in the oil and gas sector. The Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) launched its first competitive oil and gas licensing round, offering several blocks to international bidders. Changes are also underway in Asian countries like India and Indonesia, which are reforming their fiscal regimes to ease the financial burden on investors.

Effectiveness

The list of reforms around the world is much longer. It is hard to believe that they will have no impact on investment, especially given the ongoing recovery in oil prices. Of course, one has to consider the time lag between policies being announced, implemented and making an impact. There is also a big difference between getting reforms down on paper and making them work in practice.

Some would even argue, with some justification, that government moods are as volatile as the oil price. Any uptick in investment may encourage some shortsighted governments to believe that they can reverse reforms or introduce tax increases without considering the consequences.

But this has always been the nature of the business. Regulatory uncertainty is just one of many risks, from geological to commercial, fiscal and political. So far, the oil and gas industry has managed to sail through. Today’s real threat to investment is not the oil price, but whether the industry believes it has a role to play in a greener future. One could argue, however, that this worry is still decades away.