German growth sputters: Should Europe brace for trouble?

In 2018, Germany’s growth dipped. It is likely to continue sputtering in 2019 and beyond. Too many European companies have become exceedingly dependent on the German economy, and few seem capable of restructuring their production.

In a nutshell

- Germany is suffering from inadequate productivity growth

- In the longer term, German entrepreneurs will respond by relocating production abroad

- This scenario will help keep German companies competitive but bodes ill for the European economy

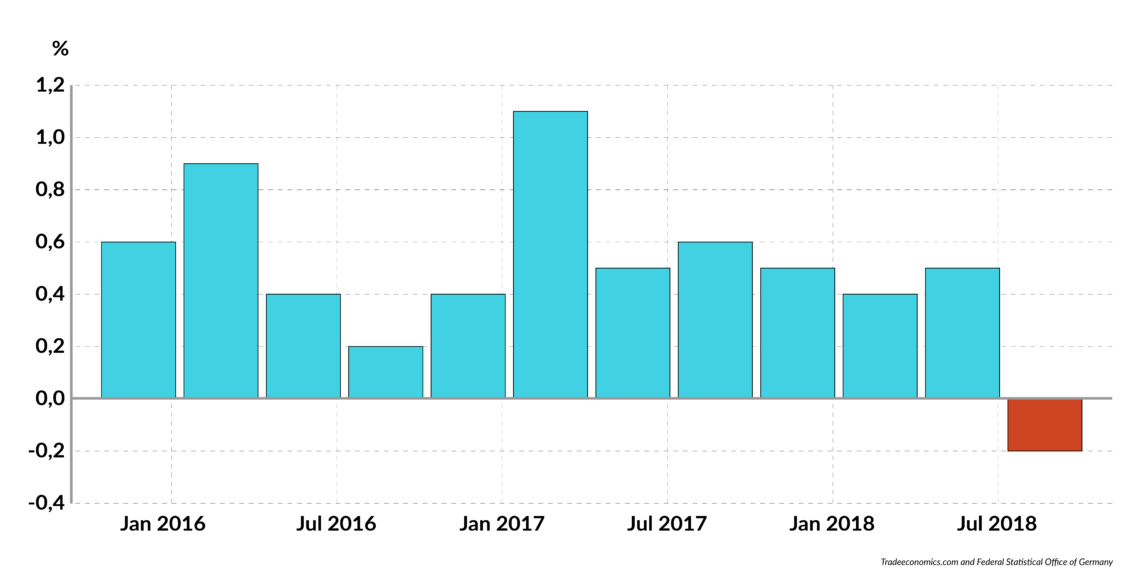

The latest data on Germany’s economic performance is not particularly encouraging. After having grown at an average quarterly rate of some 0.5 percent for the past five years, the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) declined by 0.2 percent in the third quarter. In truth, this decline was expected, so that the predictions for full-year growth in 2018 are currently confirmed at about 1.7 percent, down from 2.2 percent in 2017.

Growth during the next two years is expected to remain below the 2 percent threshold, and some observers fear it might drop to about 1.5 percent. The slowdown is not dramatic, since this year’s German growth is only slightly below the European Union average of some 1.9 percent. Yet, two issues justify concern.

First, the German slowdown is more significant than the figures show because the 0.2 percent decline occurred despite a significant rise in inventories, which are a component of growth, but often signal unsold products. Secondly, most of the decline was due to foreign trade: exports dropped by almost 1 percent, while imports rose by 1.3 percent.

Vulnerable powerhouse

Is the third quarter’s sudden stop a transitory phenomenon – which has happened before – or should we brace for a different growth path in the next few years? In this report, we draw attention to three key variables – world growth, world trade and German productivity – and consider how their future trajectory will shape the performance of the German economy and Europe as a whole.

Facts & figures

Germany's GDP growth

The trend in world economic growth is clear. Unless major shocks occur, German companies will benefit from rather healthy growth on a global scale. They will also face significant challenges. Next year, Chinese expansion might dip to just about 6 percent, or perhaps even lower, and some highly indebted developing countries could be in trouble as interest rates rise. If German exporters intend to keep playing a major role on international markets, they will have to address both issues.

Germany is not in the line of fire from Washington or Beijing but remains vulnerable to disruptions in trade.

Trade problems have been contained and the rise of protectionism has not escalated into a trade war. Even though the volume of world trade would be hard-pressed to match its 2017 increase of about 4.5 percent, data for 2018 showing a rise of better than 3.5 percent constitute a more than satisfactory performance and far outstrip earlier pessimistic forecasts. Yet, the problems noted by many observers have not vanished, and even though Germany is not in the line of fire from Washington or Beijing, it remains vulnerable to disruptions. Indeed, one may wonder why German exports are losing momentum despite the relatively good trend for world commerce.

Critical element

The third variable is German productivity. The country’s labor market is tight (the unemployment rate is currently at 3.3 percent, and 6.2 percent for young people), especially if compared with the rest of the EU, where the corresponding figures are 6.7 percent and 14.9 percent, respectively.

At the same time, job vacancies are declining and the rise in real wages is moderate (0.5 percent annually). Perhaps German companies have already started adjusting to what they perceive as a severe bottleneck. Somewhat surprisingly, however, Germany is suffering from inadequate productivity growth. Its productivity remains considerably higher than in most European countries, but productivity growth has slowed and the outlook is not encouraging. Data on numeracy and literacy among German youth is troublesome and many Asian competitors are catching up.

Investments in Germany are still growing (by an annual 1.5 percent in real terms), but not enough to ensure that technological progress moves from laboratories to the production line. The fact is that investment growth is slowing down globally – from 5.1 percent in 2010 to 2.5 percent in 2016 (in real terms). Yet, Germany is not competing with the world in general, but with its upscale manufacturers, and these are still investing heavily. When leading producers lose a step, it does not take long before they are overtaken by new leaders. Competitive pressure is relentless in the higher market niches.

Wait and see

Given this overall picture, two scenarios open up. Both feature relatively slow growth for Germany. For the German economy to grow at a significantly faster pace (say, close to 3 percent), investment spending would need to accelerate and feed through to higher output, while some key export markets (including China’s) would also need to rebound. Both requirements are unlikely to be met soon. Interest rates are low (which means borrowing is cheap), but the geopolitical context is fraught with uncertainties, which discourages long-term, high-tech investments in mature markets such as Europe.

As a result, a wait-and-see attitude will prevail among German manufacturers. Moreover, even if entrepreneurs decide to upgrade their fixed capital, it will take time before the new machinery/equipment becomes operational. In the meantime, growth will remain sluggish. Similarly, even if the drumbeat of sanctions and sanction threats has subsided, and all the big players appear to be acting rather prudently, a generalized swing in favor of unqualified free trade is unlikely. The resulting limbo will be a burden on growth, especially for trade-based economies.

Scenarios

One scenario for Germany, therefore, assumes prudent corporate spending, at the cost of slower growth. Annual GDP growth would remain between 1.5 percent and 2 percent, with exporters playing defense. Companies would use their cash flow to pay down debt before borrowing costs rise (even if this author doubts interest rates will increase significantly in 2019-2020). In this context, investments would focus on replacing obsolete machinery and introducing labor-saving equipment rather than on expanding output.

Some funds would probably be devoted to labor force training needed to operate more sophisticated production systems. This is the most likely scenario in the near future. It would be acceptable for Germany, which does not need fast growth to fix its structural problems. The German economy does not suffer from unemployment or fragile public finances; overregulation and a heavy tax burden carry a cost but have not yet killed entrepreneurial spirit and ambition.

Who should worry

Yet, this scenario does not bode well for Europe, where many economies depend on German prosperity. This is so not just because Germany is a crucial export market for EU companies, but also because many EU exporters rely on German leadership to open up export markets in the rest of the world. Without this assistance, most European economies will suffer because their companies are ill-equipped to seize opportunities that will materialize in coming quarters to compensate for slower German growth.

A different scenario would emerge if Germany suffers only a temporary slowdown, and if German entrepreneurs step up their foreign investments and relocate production capacity overseas. In this case, the new offshore facilities may end up relying on German-based suppliers in selected, high-tech segments. This would be good news for Germany and the better qualified German workers, whose skills would be in even higher demand.

The picture would be less than exciting for EU suppliers that cannot meet stringent German requirements in the upscale segments, and for European producers competing with the new and even more efficient global manufacturers cooperating with relocated German companies.

To summarize, we believe that the German slowdown is not temporary, and that the structural reforms Germany and other EU economies need to jump-start growth are not in sight. German entrepreneurs will probably wait some time before they react. When they do, it will be through massive relocation – as evidenced by German foreign direct investment and cooperation agreements on a global scale.

As Germany braces for the 2020s, companies will put their affairs in order and set aside the cash needed to enter a new period of globalization and muddle through eventual trade skirmishes. Whatever the details, the broad trend of European decline will continue, and Germany will pay less and less attention to the old continent.