Iraq at a crucial moment (Part 1)

The new prime minister of Iraq, Adel Abdul Mahdi, was reportedly chosen at a meeting in Beirut by Iran’s Revolutionary Guards Corps and Hezbollah leaders. Yet, the man they chose is far from radical. Examination of Mr. Mahdi’s career shows him to be an experienced, honest and gutsy politician, friendly to the U.S. and hardly in Tehran’s pocket.

In a nutshell

- Iraq’s choice of prime minister and president breaks the mold of traditional politics

- Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani’s intervention was decisive in picking a moderate

- Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi has the skills to tackle Iraq’s manifold problems

Iraqi democracy took a new turn in 2018, breaking with some traditional patterns. In the May elections, many Sunnis joined Shia-controlled coalitions. Sairun, led by the junior Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, had the most surprising makeup, crossing the religious divide to attract communists and other secular groups. More ominously, armed militias (all of them pro-Iranian) ran as political parties for the first time, making no attempt to present themselves as civic organizations.

The turnout of 44.5 percent on election day was disappointing. It compared poorly with the 70 percent of eligible Iraqis who voted in 2005, and with the 60 percent in 2014. Low participation is evidence of the disillusionment most Iraqis feel about their government.

Iraq’s new parliament endured four months of political deadlock before electing a speaker, Mohammed Al-Halbousi, on September 15. Since 2003, there has been an unwritten law that the Iraqi speaker must always be a Sunni. Mr. Al-Halbousi, a 37-year-old leader from the al-Halabsa tribe in Anbar, is a former governor of his province. His political orientation is controversial, however, because he is clearly pro-Iranian. He began cooperating with Tehran in 2015-2016, when pro-Iranian Shia militias helped government forces oust Islamic State from Anbar.

Through those militias, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) recruited many Sunni tribal sheikhs, among them Mr. Al-Halbousi. He visited Tehran on several occasions, received financial support and joined a pro-Iranian parliamentary coalition. Even after a meeting of young Halabsa men declared him a “traitor” for supporting pro-Iranian factions, Mr. Al-Halbousi was not deflected from his course. Upon being elected as parliamentary speaker, he denounced the reimposition of United States sanctions on Iran and invited his Iranian counterpart, Ali Larijani, for a visit. This marked a major setback for American interests.

The Iraqi parliament’s next two personnel decisions, however, were more balanced.

Kurdish split

Also in September, the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) decided to propose their own candidate for the Iraqi presidency. By doing so, they broke a tradition by which the KDP decides who is president of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), while the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) picks the president of Iraq – a ceremonial position that has long been given to the Kurds. In response, the PUK ignored the practice of accepting a joint Kurdish candidate and went directly to the parliament in Baghdad with their own – Barham Salih.

Until Barham Salih turned the tables, the Iraqi presidency had always conferred honor, not power.

The result was a predictable humiliation for the KDP. On October 2, Mr. Salih was backed by 219 of the 329 deputies in parliament, while his KDP opponent got only 22 votes. The overwhelming support for Mr. Salih was hardly surprising. Almost all Arab legislators, Shia and Sunni alike, preferred a PUK candidate because that party has always been less insistent on Kurdish independence and more supportive of the central authorities in Baghdad. Likewise, the Iranians had historically enjoyed good relations with the PUK and wished to keep it that way.

This unusual breach in Kurdish solidarity stemmed from the KDP’s rash decision to conduct an independence referendum in September 2017. The overwhelming “yes” vote prompted the Iraqi army to seize the city of Kirkuk and its vital oil fields, along with other Kurdish-occupied territories outside Kurdistan’s formal boundaries, in October 2016. When the Iraqi troops rolled in, the PUK abandoned Kirkuk, forcing the KDP’s Peshmerga units to follow. This was a humiliating reverse for the KRG and widened the already huge rift between the two main Kurdish parties.

Until now, the Iraqi presidency has conferred honor, not power. That is why, since the downfall of Saddam Hussein, the post was always given to a Kurd. Even Saddam habitually appointed a Kurdish vice president. This time, however, Mr. Salih turned the tables.

Beirut meeting

The day he was elected president, ignoring the traditional procedure of consulting the major parliamentary parties, Mr. Salih announced his pick for Iraq’s new prime minister: Adel Abdul Mahdi, a 76-year-old economist and veteran Shia politician. This snap decision was unprecedented and took most legislators by surprise. However, serious Iraq watchers had been put on notice one month earlier – by media reports that the country’s future had been settled in Beirut, of all places, during the meeting of a Shia power trio.

The three principals were Muqtada al-Sadr, whose Sairun coalition is the largest group in Iraq’s parliament; Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Hezbollah in Lebanon, and Major General Qassem Suleimani, the commander of the elite Quds Force of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC). The men reportedly agreed that Adel Abdul Mahdi was the right choice for Iraq’s prime minister. Most likely, they also approved Barham Salih for the Iraqi presidency.

The three-way meeting showed that Iran already sees Iraq as part of the Tehran-Damascus-Beirut axis.

While the profound influence of the IRGC and Hezbollah in Iraq had long been appreciated, these reports placed it in a dramatically different light. Most of all, the three-way meeting in Beirut – which has come to serve Tehran as a hub for regional operations – demonstrates that Iran already considers Iraq as an organic part of the Tehran-Damascus-Beirut axis.

Less than two months after the purported meeting, on October 25, 2018, Adel Abdul Mahdi was sworn in as Iraq’s new prime minister.

Making a deal

How these key personnel decisions were arrived at is worth tracing, because the process was complex and far from automatic.

For the post of Iraqi president, the need was for a skillful mediator along the lines of Jalal Talabani (2005-2014), who successfully steered between rival factions in Baghdad for almost a decade. Mr. Salih’s background as an envoy to the U.S. and Iraqi deputy prime minister in the mid-2000s gives him the necessary qualifications as a political arbiter. His quick appointment of Mr. Abdul Mahdi as prime minister, however, was only possible because parliament could not muster a workable majority.

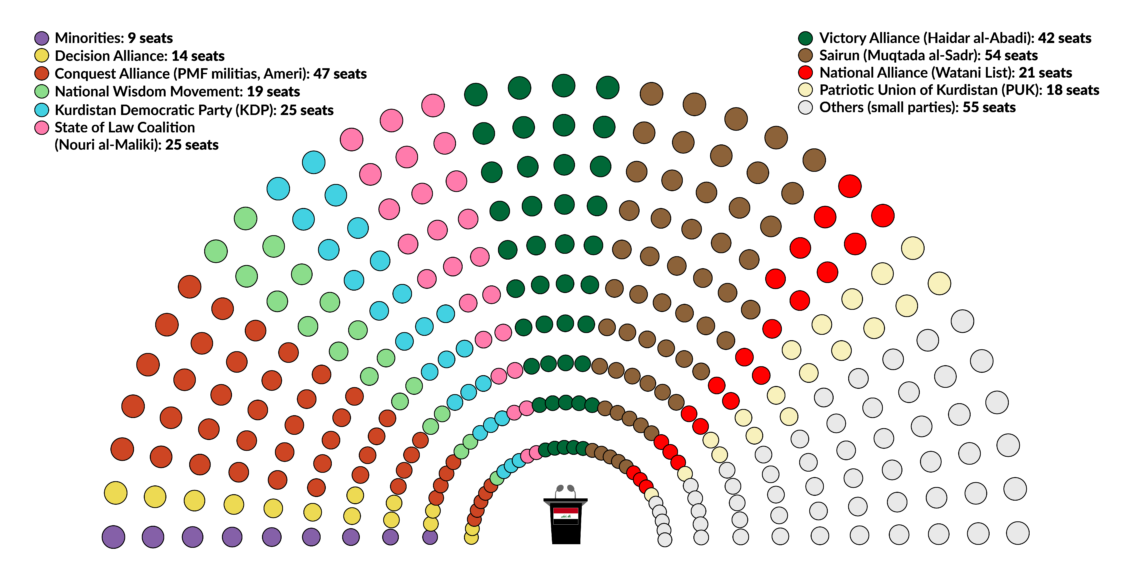

The biggest coalition, forged between Mr. al-Sadr’s Sairun and the Victory Alliance (al-Nasr) of former Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi (2014-2018), held only 96 seats – not even 30 percent of the legislature. They represented a centrist course, pushing for anticorruption, national self-determination, keeping Iran at arm’s length, moderation toward the Kurds, avoiding tensions with the U.S., and keeping close ties with Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the Emirates.

Facts & figures

Composition of Iraqi parliament

(Parties and coalitions, 2018)

However, even support from all 43 Kurdish deputies would have left these centrists far short of the 165 seats needed to form a majority. The rival Shia coalition between former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki (2006-2014) and militia leader Hadi Ameri, which controlled a combined 73 seats, had even less of a chance.

Into this standoff stepped Iraq’s senior Shia cleric, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani. During the backroom talks between the May elections and September 2018, the 88-year-old hierarch made his views known – a departure from his usual aloofness from politics. He insisted that no politician who had held high office should take the premiership, because past governments had failed. Apparently, he exempted Mr. Abdul Mahdi, who had served as finance minister, vice president and oil minister in previous cabinets, on the grounds that he had not failed and had resigned his last post.

By supporting Mr. Abdul Mahdi’s candidacy, Ayatollah al-Sistani denied the premiership to Iran’s staunchest supporters, Mr. al-Maliki and Mr. Ameri, while securing it for a middle-of-the-road politician who maintained good relations with both the U.S. and Iran. It was typical of Ayatollah Sistani that he never considered deep piety to be a relevant qualification. He would never approve of a Sunni prime minister, but Mr. Abdul Mahdi is a rather secular figure and a moderately observant Shia Muslim, nothing more.

Iran’s readiness to compromise can be traced to the traumatic events in southern Iraq.

Long before the president and prime minister were chosen, it became clear that the Maliki-Ameri camp would never back Mr. Al-Abadi for another term at the head of government. After street riots broke out in Basra, Mr. al-Sadr also decided in September to withdraw his support from Prime Minister Al-Abadi. In this, he was in complete agreement with Ayatollah al-Sistani. Both men wanted new faces in the cabinet, preferably technocrats.

Since Mr. al-Maliki was tainted by an outrageously corrupt and ineffective eight years in power, his relatively weak parliamentary alliance with Mr. Ameri had no option but to accept the Abdul Mahdi candidacy. Two facts helped them accept defeat. Firstly, there was no clear antagonism between the prime minister-designate and themselves. Secondly, Tehran did not strongly oppose Mr. Abdul Mahdi, either. The reason why Iran was so ready to compromise can be traced to the traumatic events in southern Iraq.

Iran gives in

Starting in July 2018, Iraq’s main port and second largest city, Basra, along with large areas of the Shia-dominated south, were swept by massive anti-government and anti-Iranian demonstrations. These street protests signaled to the ruling elite that the time for procrastination was over.

The pro-Iranian Maliki-Ameri coalition did its best to exact concessions from Mr. Abdul Mahdi in return for their support. Their wish list began with critical cabinet portfolios, including interior, oil, finance, tourism and development. For his part, Muqtada al-Sadr, anticipating such demands, announced that the Defense and Interior Ministries, along with all aspects of domestic security, must stay under the prime minister’s direct control. This suggests Mr. Sadr wants the powerful pro-Iranian militias, the 100,000-strong Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), brought to heel.

Two outside players, Iran and the U.S, could not be ignored. As mentioned earlier, President Salih’s relations with Tehran have been good since at least 2015. As for Prime Minister Abdul Mahdi, his ties to the Iranian regime go back to Ayatollah Khomeini’s triumphant return to Tehran in 1979. While the Iranians would have preferred a more compliant figure like Mr. al-Maliki or Mr. Ameri at the head of the government, they decided that Mr. Abdul Mahdi will do.

Both Prime Minister Abdul Mahdi and President Salih have always been friendly toward the U.S.

Partly this was a tacit quid pro quo with the Americans. In 2010, President Barack Obama’s administration succumbed to Iranian pressure and agreed to let Mr. al-Maliki stay on as prime minister. His disastrous second term was one of the main reasons for ISIS’s spectacular success in capturing most of northern and western Iraq in 2014. Now it was Iran’s turn to give in.

Whether this resulted from Tehran’s weakness or inside knowledge is difficult to judge. Suffice it to say that both Mr. Abdul Mahdi and Mr. Salih have always been friendly toward the U.S. Mr. Salih lived for many years in Washington, D.C., while Mr. Madhi worked closely with the American authorities in Iraq in the mid-2000s.

Eternal oppositionist

Perhaps the most telling aspect of Adel Abdul Mahdi’s career is that over a half century, he has belonged to almost every single political camp in Iraq, without staying anywhere for very long. Mostly, he found himself in opposition to the ruling regime. Over the past several years he has been an independent, and he ran as such in the 2018 parliamentary elections. An able economist with extensive policy experience, Mr. Abdul Mahdi has a reputation for being incorruptible.

He was born in the Shia city of Nasiriyah in 1942 to a respected clerical family. His father served briefly as minister of education under the monarchy (1921-1958). Despite their religious background, his parents sent him to the American Jesuit College in Baghdad, then probably the best high school in Iraq. He earned an economics degree from Baghdad’s College of Trade and Economics in 1959.

Under the regime of Prime Minister Abd al-Karim Qasim (1958-63), Mr. Abdul Mahdi was close to the opposition Baath party. During the rule of the Arif brothers (1963-1968), he became first a member of the underground Iraqi Communist Party (ICP), then joined that party’s Maoist wing.

Soon after the Baath Party took power in July 1968, the nascent regime conducted a ferocious anti-Maoist purge. Mr. Abdul Mahdi fled to France, where he studied political science and economics. He then worked for several research centers on Islamic studies, edited Arabic and French-language publications, and translated and wrote a number of books. During this period of exile in the 1970s, he was close to the French non-Communist left.

Mr. Abdul Mahdi was a supporter of the Shah of Iran until 1975, when the Shah chose to sign the Algiers agreement with Iraqi Vice President Saddam Hussein, ostensibly resolving the border disputes between the two countries. He then backed the Islamic Revolution in Iran that brought Ayatollah Khomeini to power, hoping that it would lead to the establishment of an Islamic republic in Iraq, too.

In 1982, Mr. Abdul Mahdi joined Ayatollah Mohammed Baqir al-Hakim’s Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI), serving as its representative in Kurdistan in 1992-1996. This gave him close access to the Kurdish leadership and a good understanding of Kurdish-Arab relations. From this stage, if not earlier, Mr. Abdul Mahdi has favored a Kurdish-Arab federal system in Iraq. He is a staunch supporter of democratic government, but also believes that senior Shia clerics should exercise indirect political influence.

Abdul Mahdi’s moment

Mr. Abdul Mahdi’s years of exile and opposition ended with the U.S. invasion of Iraq, which destroyed the Baath Party for good and established a new political system into which he fit well. With Ayatollah Sistani’s blessing, and backed by SCIRI and the Islamic Dawa party (whose leadership included future Prime Ministers al-Maliki and Abadi), he was more than ready to work with the Americans on creating a new Iraq.

Yet this cooperation was also risky; some “collaborators” were assassinated by the Iraqi resistance to U.S. occupation. After a brief stint as finance minister, Mr. Abdul Mahdi was chosen as vice president following the January 2005 elections, representing the Shia community. Later, under Prime Minister Abadi, he served as oil minister from 2014 to 2016.

No one else has Mr. Abdul Mahdi’s combination of incorruptibility, economic expertise and experience.

Unlike Muqtada al-Sadr on one hand and the pro-Iranian Shia militias on the other, Mr. Abdul Mahdi never called for American forces to withdraw from Iraq. Indeed, as late as December 2011, he seems not to have considered Iraq capable of defending itself. This was an unpopular position. The prime minister’s personal courage is also evident from his stated intention of living outside Baghdad’s protected Green Zone while he is head of government.

Hidden strength

If ever there was an experienced politician whose resume seems tailor-made for Iraq’s present needs, it is Adel Abdul Mahdi. No one else in Baghdad has his combination of incorruptibility, economic expertise and practical experience. Until now, he has always got what he wanted without making serious enemies among Iraq’s major political players.

Together, Prime Minister Abdul Mahdi and President Salih present a formidable duo in terms of professionalism and negotiating skills. Mr. Abdul Mahdi will need every bit of his expertise, because the tasks ahead of him are gargantuan. They start with the formation of his government, which began even before he was sworn in. Most of the cabinet lineup was announced on October 24-25, but parliament approved only 14 of his candidates, rejecting eight others because of alleged corruption or ties to the Saddam regime.

By far the most important vacancy is the Interior Ministry, which controls internal security. Here the government’s two main backers – the Sadr-Abadi and Ameri-Maliki alliances – are at odds, with Mr. al-Sadr insisting on professional appointees rather than party or militia representatives.

However, these seemingly insurmountable obstacles may not be so difficult for Mr. Abdul Mahdi. Like a martial arts master, he has turned weakness into strength. Precisely because the prime minister has no political grouping of his own, the fractured coalitions in parliament desperately need him as an arbiter. His fall would be perceived as their failure. As a result, even a veiled threat to resign, which Mr. Abdul Mahdi hinted at in mid-November, will give them pause.

The new head of government also has plenty of carrots to dispense, including jobs and salaries for PMF members. Few Shia militiamen will be able to resist such temptations. Mr. Abdul Mahdi has a long list of contacts abroad, including a quiet understanding with the Gulf Arabs that looks promising, as long as he does not tilt too much toward Iran. When the time comes for investment funding and perhaps even broader economic support for Iraq, those friendships could pay off handsomely.

Click here for Part 2 of this report.