Public debt spells trouble for the U.S. economy

If growth slows and the U.S. government fails to cut public expenditures, an economic crisis will likely follow.

In a nutshell

- The U.S. is on track to overcome inflation without slipping into a recession

- Further expansion of public debt will lead to a severe crisis

- Prioritizing spending cuts over tax increases will be crucial for stability

The United States economy has had a good run. Gross domestic product (GDP) growth is encouraging (2.5 percent in 2023 and more than 3 percent during the last 2023 quarter), and the February 2024 price inflation rate was down to 3.2 percent – higher than expected but still a commendable result.

The labor market is in great shape. Last February, the unemployment rate was 3.9 percent, and in January the job openings rate was 5.3 percent: although this figure is dropping, it remains significantly higher than it averaged in the past (3.5 percent). In other words, unemployment is not a problem, and the demand for labor is vibrant.

This is, of course, good news for the U.S. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, and President Joe Biden now has plenty of encouraging economic results to support his reelection bid. There are a few clouds on the horizon, however.

Interest rates and ‘corporate debt cliff’

Many assumed that the Fed would soon make credit less costly and more readily available – but they have been disappointed. The Fed’s 2 percent inflation target may not be achieved by the end of this year, and there are fears that tight monetary conditions might weaken GDP growth. Such worries are partially justified.

Many American companies took advantage of the long period of abnormally lax credit conditions. They borrowed heavily, especially during the worst of the Covid-19 pandemic, and a large share of those debts are to mature in the next couple of years. Many companies will not be able to pay them back and will try to refinance their past borrowing through new loans.

No one knows what the interest rates should be because the authorities keep manipulating money and credit markets.

The cost of debt servicing on those new loans is undoubtedly going to be higher than anticipated. If interest rates do not drop significantly during the next quarters, many balance sheets will take a heavy hit, and some borrowers could go broke.

This is the so-called “corporate debt cliff” created by years of irresponsible monetary policy. Depressed interest rates ended up rescuing inefficient businesses that should have suffered losses or gone bankrupt a long time ago. Instead, they kept draining scarce resources from the healthy part of the economy. The cliff will, at long last, eliminate the poor performers, but it will not be painless.

Doing the right thing

There is also some good news. Broadly speaking, the monetary picture is improving. Regrettably, no one knows what the interest rates should be because the authorities keep manipulating money and credit markets, but the Fed is aware that there is much liquidity around. The nominal money supply (M2) is currently just below its 2022 peak and twice as high as its 2014 level. Indeed, keeping interest rates relatively high is the only way of eliminating the monetary overhang.

In other words, the Fed is doing the right thing and, hopefully, will stay the course even after the presidential election. Its policy of steadying the monetary picture will draw some flak and take time. However, it produces a welcome result: The probability of reducing inflation without causing a recession (a “soft landing”) is considerably higher today than it was just a year ago.

The government keeps adding to the debt

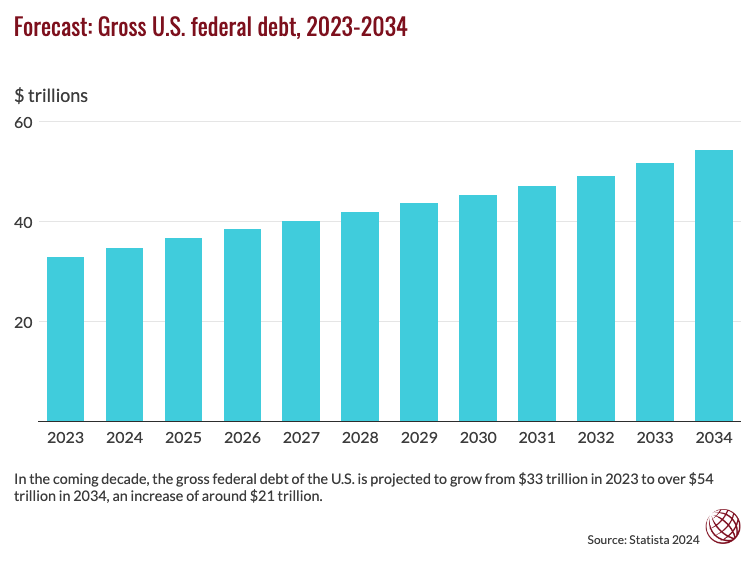

Another, and potentially more severe, threat is public finance. At the end of 2023, the U.S. government debt was about 124 percent of GDP. This figure is below the 2020 peak of 127 percent, but it is still high.

Read more on central bankers’ dilemmas

- How markets revealed the myths of central banking

- The European Central Bank’s monetary policy is under pressure

- The secular threat of inflation and debt

- Expect neither a recovery nor a recession

On the one hand, there is bad news for the Department of the Treasury: the budget deficit continues to add to the accumulated debt; the Fed seems unwilling to buy U.S. securities (Treasuries) to the extent it did in the recent past; and relatively high interest rates make debt servicing expensive. On the other hand, there is good news: productivity has increased faster than expected and generated enough growth to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio and keep markets happy.

Facts & figures

Moreover, the rise in productivity has not been matched by an increase in salaries. Thus, profits have been rising, and more investment resources are available. The debt burden is heavy, but the economy is in good shape, and there is no shortage of buyers of U.S. securities.

However, some caution is in order. The 2024 budget deficit is expected to be 5.6 percent of GDP. Of that, 2.5 percent is the so-called “primary deficit” (the fiscal deficit for the current year minus interest payments on previous borrowings), while 3.1 percent is debt servicing. Now, since about one-third of the U.S. public debt must be refinanced by the end of 2024 at interest rates higher than those obtained in the past, the cost of debt servicing could rise by about 0.4 percentage points, to some 3.5 percent of GDP. Hence, the key to stabilizing the burden of debt is the primary deficit, which must not exceed the current level – or drop if growth slows down.

The government’s ability to cut its primary deficit will be crucial to making room for more debt servicing.

The real yield on the 10-year Treasury is currently about 1 percent, which is not high by historical standards, especially if the economy grows faster than 2 percent. It is reasonable to expect that real interest rates will rise further, especially if corporate America remains in good health. Regardless of Mr. Powell’s hints to the contrary, the margin for a nominal interest rate cut is limited.

If private companies offer better investment options, it might be difficult for the government to sell its bonds unless it provides a high coupon (the annual interest rate) to attract investors. Put differently, markets do trust the U.S. dollar as a safe currency and the U.S. government as a solvent debtor. However, suppose companies believe that this high level of productivity growth is going to last. In that case, corporate bonds will flood the market, and debts – private and public – will be financed or refinanced at relatively high rates.

Scenarios

Companies’ and households’ responses to monetary policy will play a crucial role in upcoming developments. If the Fed cuts interest rates by half a percentage point in 2024, it will not be enough to keep poor-quality borrowers away from issuing more bonds and possibly getting closer to the corporate debt cliff. The Fed will be watching the money supply (rather than inflation) before it gives into pressure. The government’s ability to cut its primary deficit will also be crucial to making room for more debt servicing.

In the end, the scenarios depend on growth. Three developments are possible.

Not very likely: Strong growth eases the debt pressure

If productivity continues to rise and the economy maintains its current momentum (about 3 percent GDP growth), the U.S. will have time and room to fix its weak point: fragile public and private debtors.

Possible: Government is forced to cut spending

The productivity growth may peter out. In past quarters, productivity rose because companies increased their efficiency in response to the Covid-19-caused slowdowns and supply bottlenecks. This push is no longer as strong, and it is probably too early for artificial intelligence to change the productivity picture. Should growth drop below 2.5 percent (many commentators forecast it will be between 2.0 percent and 2.5 percent), the government will pass legislation aiming at cutting public expenditure before the end of the year.

Most likely: The ‘do nothing’ option

This scenario is similar to what is currently taking place in the eurozone. If the U.S. government fails to react to sputtering growth, the country will see severe consequences in the next couple of years. The aggravated public debt crisis will create uncertainty, harm investments and ultimately further depress economic activity. A dangerous downward spiral of political and economic trouble will follow.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.