The Italians learn Chinese: should others in the EU follow their lead?

During Chinese President Xi Jinping’s March visit to Rome, Italy and China signed a set of agreements that bring the former very close to Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative community. Although France, Germany, and the U.S. expressed, such a deal may be in Italy’s vital interest, given its deteriorating economy and financial conditions.

In a nutshell

- Rome is desperate for institutional financial investors willing to finance Italy’s increasingly massive public debt

- The country is also groping for new infrastructure investment and infusion of new technologies

- The EU currently treats the newly powerful China as more of a part of the problem than a solution, but this attitude may change

Italy’s foreign policy rarely makes headlines in the global media. Its political leaders prefer to concentrate on domestic affairs. In the international arena, Rome has been happy to follow the guidelines suggested by the United States and the NATO alliance. In some cases, this quiet obedience turned out not to serve Italy’s best interests (such as the 2011 military action against Libyan strongman Muammar Qaddafi). Overall, the West has considered Italy a loyal ally, both militarily and in terms of global foreign trade strategy.

Last March, however, after having embarked on rather questionable reforms to the detriment of economic growth and budgetary prudence, the Italian government managed to make Western diplomats uneasy. It started its own foreign policy with China and joined the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) project – apparently with no prior consultation with Brussels or Washington.

Powerful partner

The legacy of Chinese president Xi Jinping’s March 2019 visit to Italy is twofold. Rome and Beijing have agreed to pursue a common strategy to intensify reciprocal trade and investment flows, as well as to developing joint technological projects. Moreover, Italy has decided to take an active role in the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Italy has decided to go in for its own trade and financial relationships with China and ignore the possibility of developing a shared view together with its EU partners.

Italy is aware that Germany and France will be shaping the EU’s commercial relationship with the rest of the world.

What triggered that decision? And what consequences can one expect? To assess the extent to which the Italian move might affect future geopolitical scenarios, a few words about the Italian and EU context are in order.

Italy is currently aiming at different targets. The not-so-credible policymakers in Rome are eager to find powerful institutional financial investors willing to finance Italy’s increasingly sizeable public debt and, possibly, the development of new infrastructure (Genova and Trieste would be heading the list of the candidates for Chinese facilities). They are also trying to attract new business to invigorate the country’s stagnating entrepreneurial sphere and avoid ongoing recession. The government is desperate for high-tech initiatives.

Moreover, the Italian leaders are aware that Germany and France will be calling the shots in the future shaping of the EU commercial relationship with the rest of the world. Italy’s needs and interests do not necessarily coincide with those of the two largest EU members.

From Beijing’s viewpoint, Italy is a possible springboard for developing Chinese production in the EU area, but the value of Italy would weaken if other relatively large EU countries made similar offers. France and Germany, for their part, are currently inclined to promote their technological champions and to discourage the Chinese from entering the European technological market, especially regarding manufacturing. Shortcuts and backdoors are not welcome, and the Italian route is perceived as an attempt to circumvent such barriers.

Conflicting perspectives

Italy needs help from outside and, at this moment, such assistance can only come from China, for which Italian treasury bills and ailing companies like Alitalia are much more valuable than market prices would suggest (but less valuable than the Italian politicians assume). In this light, Italy must move before the EU develops its own political and commercial strategies toward Beijing and before Brussels ends up stultifying what Rome considers the low-cost solution to its structural problems.

Facts & figures

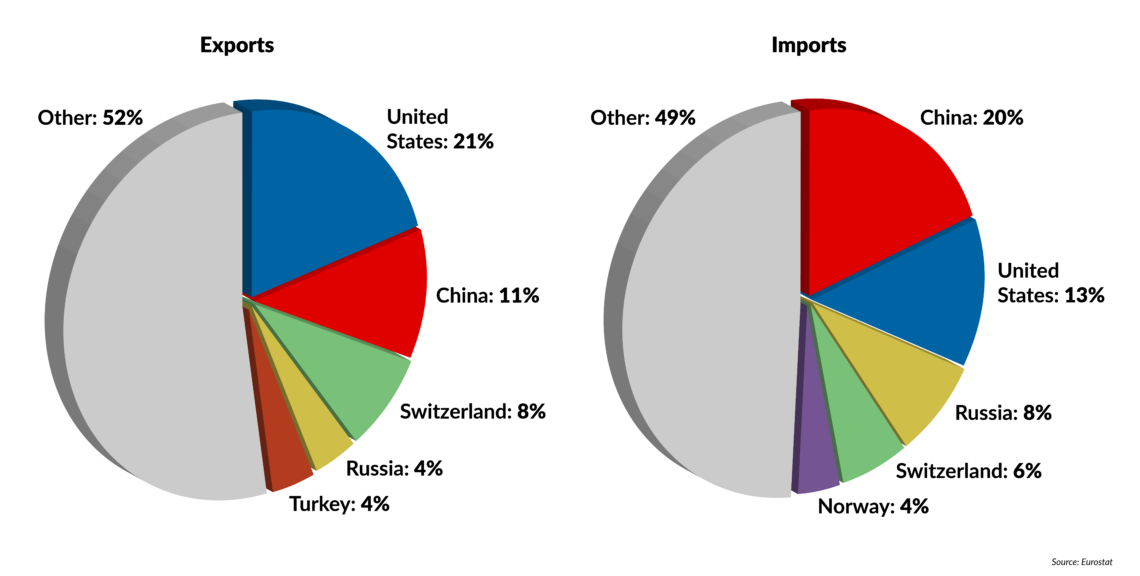

The position of China among the EU-28's main partners for trade in goods, 2018

Indeed, Italy believes that dealing with China in purely commercial terms – the Franco-German option – will not last, as it is only an intermediate phase before greater economic integration between the two blocs: China and the EU. On the other hand, the Franco-German bloc believes that finance and technology should be the essence of the strength of the EU in future geopolitical scenarios, and that autonomy in those areas remains crucial if Europe wants to play any significant role.

The deal between Airbus and China is much larger than the commercial agreements the Chinese recently signed in Rome.

In this respect, the Italian openings are a serious crack in the political and economic structure the Europeans want to realize in the next few years, possibly in cooperation with the U.S. Certainly, the crack would seriously widen if Italy doubled down and agreed to similar grand projects with Russia.

To be fair, it is not clear that the Italian leaders are consciously pursuing a grand strategy for the next couple of decades. At times, one has the impression they fail to realize that joining China’s huge infrastructure project is not the same as exporting or importing aircrafts, even if the deal between Airbus and China – signed during President Xi’s same trip to Europe last March – is eight times larger than the commercial agreements the Chinese recently signed in Rome. Furthermore, the Italians might not be fully aware that the Chinese are tough businesspeople: they buy only at fire-sale prices and engage in negotiation practices that will leave the Italian bureaucracy gasping.

So, what does the future hold? Geopolitical games are a mix of power, credibility and political cunning. It is indisputable that the current Italian leaders lack the culture and guile to interact with key actors on the world stage. Likewise, it is undeniable that their inadequacy is a threat to Italy’s future credibility. The critical issue, therefore, is establishing whether the EU will have a common policy toward China and whether it can ignore loose cannons. Italy is currently rocking the boat, but it might not be an outlier: in 2016, Greece also let the Chinese in. Other countries could follow in the future, especially if the EU does not prove fit for the needs of the time.

Scenarios

Two distinct possibilities open up. According to one scenario, the EU authorities would insist on considering regulation that designates national champions as the key to the future economic development of Western Europe and the main reason for pursuing a continental industrial policy. This would lead to subsidies and protection against foreign competitors – and also to difficulties in creating companies large enough to sustain the high cost of long-term technological development and commanding extended supply chains needed to become economic players on a global scale.

So, this is a somewhat risky development strategy. A bureaucratized and highly regulated Europe might please the Americans, especially if Brussels follows Washington’s lead in foreign affairs. However, within such a context, Europe will hardly become the land of groundbreaking innovation and winning competitors. China might be kept at bay, but Europe’s best companies would migrate.

Indeed, Italy’s choice does not look helpful within this framework. However, it is realistic. If the European economies eventually run out of steam, Brussels, too, will have to look around for some sort of economic support. Italy is making no mystery about the fact that all help is welcome, regardless of its origin. Being an early and privileged Chinese quasi-colony could bring some advantage, especially if the setup does not exclude the possibility of inviting other players as well, including Russia. Further tensions would emerge, of course, but there is little that Berlin, Paris or Washington could do about it.

A second – and less likely – scenario would materialize if the Europeans decided to change tack, recognize that Beijing is leading the race and strive to catch up by liberalizing trade flows and doing without industrial policy (including antitrust regulation and social dumping rhetoric). This does not mean that the EU member countries would join the BRI as it is currently framed. Within this scenario, however, each country would explore avenues for more in-depth cooperation. Dealing with the Chinese in isolation is probably not the best strategy: size matters, and no EU country is a match for China, while relying on the Americans would make things more complex and slow all decision-making processes. In fact, a unified EU approach would be preferable.

Yet, at this time the EU authorities do not seem ready to move in the world that the Chinese will shape in the future. Brussels seems unable to fully understand this world, let alone turn the knowledge to its advantage. After all, if Europe could deliver what it promises, the Italians would have had no need to engage in daring and (partially) new undertakings.