Scenarios for the legacy of Shinzo Abe

Shinzo Abe has made a huge imprint on his country’s politics. His eventual successor will have a host of domestic challenges to overcome, including a growing demographic imbalance. The question is if the power brokers in Japan will allow a new strong leader to emerge after Abe.

In a nutshell

- Shinzo Abe has become an unusually strong leader for Japan

- He is unlikely to complete his economic plan or repeal Article 9

- The next prime minister will face enormous challenges

In mid-November 2019, just around the time Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was able to celebrate becoming the longest-serving Japanese head of government since World War II, official figures showed a considerable slowdown in Japan’s economic growth. Taken together, the two events present an opportunity to consider the impact of Prime Minister Abe’s tenure and his much-vaunted “Abenomics” on Japan’s future.

Political longevity

While it is unclear when Prime Minister Abe will relinquish his two charges as president of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and Prime Minister of Japan, the bulk of his time in office has clearly passed. The search for a successor will gain momentum. The main question now is which elements of Abe’s legacy will remain in place.

When Mr. Abe became prime minister and party leader for the second time in 2012, he showed greater determination than during his short-lived first term, from 2006 to 2007. That initial stint at Japan’s helm was cut short by health issues. In 2012, Prime Minister Abe showed renewed vigor and made it clear that he was in the job for the long haul. At the time, no one predicted his tenure would be so protracted. Japan had had a string of short-term prime ministers.

Prime Minister Abe set out to make a lasting mark in Japanese politics.

Not only was Prime Minister Abe determined to keep his high office, he also set out to make a lasting mark in Japanese politics. His first signature initiative was dubbed “Abenomics,” a policy meant to lead the Japanese economy through several profound economic reforms.

When he launched the plans, in 2012-13, few imagined that Donald Trump would become president of the United States. Japan was sailing smoothly along in its role as the most important U.S. ally in Asia. Most observers expected this would continue under Hillary Clinton or under a moderate Republican.

Derailments

The 2016 U.S. presidential election turned those assumptions on their head. From the start, Prime Minister Abe dealt remarkably well with the idiosyncrasies of the new U.S. president. However, he could not prevent two key issues in U.S.-Japan relations – security and trade – from undergoing fundamental change. Suddenly, there was uncertainty about whether Washington would back Tokyo under all circumstances, particularly in its conflict-prone relations with China. Furthermore, the U.S. president, who adheres to a transactional approach with other countries, including close allies, made clear that Japan had to pay more for the military security that the U.S. provided.

Most importantly, President Trump was adamant that he wanted to reduce his country’s chronic trade deficit with Japan. Although the trade disagreements with Japan did not reach the fever pitch they did with China and the European Union, it was clear that Japan had to give in to American demands about restraining its exports to the U.S. Luckily, the Japanese auto industry had long ago moved much of its manufacturing capacity to the U.S.

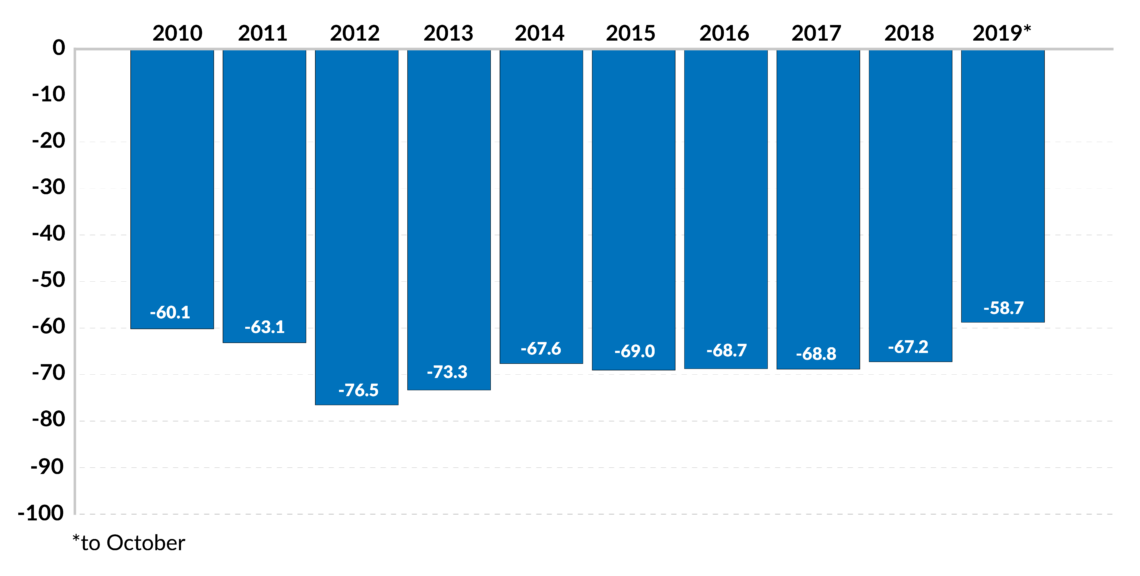

Facts & figures

Whatever the long-term impact on trade and security these shifts during the Trump administration will have, one thing is certain: Prime Minister Abe had to spend much more time, effort and political capital on external issues than on his domestic economic reforms. His task was not made easier by the fact that in recent years China has substantially increased its military muscle and has shifted to more self-confident, even aggressive posturing on security issues within its neighborhood.

Finally, Prime Minister Abe has had to manage increasingly complex challenges emerging from the Korean Peninsula. Both Tokyo and Seoul have had to adjust to working with a U.S. president who wants to build a private rapport with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un and seems not to listen to his security staff’s advice in dealing with him. Furthermore, President Trump does not consult Japan and South Korea regarding his administration’s North Korea strategy. Most worryingly for the two U.S. allies, President Trump seems to tolerate North Korean provocations (rocket launches) and further progress in its nuclear program.

Mixed record

Soon after he started his second term in office, Prime Minister Abe launched an ambitious program to stimulate the economy of Japan, which had been plagued by deflationary trends since the beginning of the century. The strategy was based on the so-called “three arrows”: monetary easing, more government spending and structural reforms.

On several fronts, the prime minister was successful. The Japanese economy has been gaining momentum. The growth rate is still modest, but the danger of a deflationary trap has been overcome. While the public deficit is still very high, Prime Minister Abe has grown revenues, most significantly by raising consumption taxes. In a bold fiscal policy move, the Abe government has, in two steps, doubled the consumption tax from 5 percent to 10 percent. Analysts predicted the change would cause a political storm and have a severe negative impact on the economy. Neither materialized.

Abe’s successor will have to deal with much bigger demographic challenges as the age curve grows even more distorted.

Other developments have offered a mixed bag of good and bad news. Though deflation has been avoided, the target inflation rate of 2 percent remains elusive, a major reason why the Bank of Japan has continued its loose monetary policy. Unemployment has decreased significantly since Prime Minister Abe took office. Particularly for first-time job seekers, the prospects have substantially improved. Yet Japan’s rapidly aging population is driving these opportunities. A rise in the retirement age has increased the average number of years of gainful employment, but Prime Minister Abe’s successor will have to deal with much bigger demographic challenges as the age curve becomes even more distorted.

Prospects: Moderate change

Bearing in mind the geopolitical challenges that are facing Japan due to the rise of China and the end of the Pax Americana in Asia, Prime Minister Abe will most likely devote his remaining years in office to issues of foreign and security policy. The long-standing ambition of the prime minister, an ambition that has its roots in his family’s political past, is the removal of Article 9 of the Japanese constitution. This article severely restricts Japan’s defense capabilities.

It is highly unlikely that Mr. Abe will be able to clear all the political and legal hurdles to remove Article 9. This does not mean that he will dedicate less time and effort to this goal. In the remaining years of his leadership, Prime Minister Abe will make every effort to give Japan a more self-reliant national defense that can project its military strength beyond its own territory.

In October 2017, Prime Minister Abe won his fourth term as prime minister. The term lasts a maximum of four years, meaning elections to the House of Representatives, the lower house of Japan’s National Diet, will have to be held in autumn 2021 at the latest. Considering his record, it is safe to assume that Prime Minister Abe will call an early election when circumstances look promising.

In 2018, Mr. Abe won another three-year term as president of the LDP. For now, there is no obvious, compelling candidate within the LDP who could seriously challenge him, either as party president or as prime minister. Equally, the opposition benches look devoid of anyone who could muster a significant challenge to LDP rule in the next elections.

None of this is to say that there are no aspirants for these high jobs. Shinjiro Koizumi, the son of former LDP leader and Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi, is increasingly being talked about. He is only 38 years old though, and may yet not be considered mature enough when the next contest for leadership takes place.

While some surprises on the foreign policy front could occur, the prospects on the economic front look fairly set for the post-Abe period. The LDP is a conglomerate of different factions. Policies are developed by consensus, with the aim of meeting the interests of a large part of the electorate and especially traditional LDP supporters, namely the agriculture sector and the construction industry.

The person (almost certainly a man) who will eventually emerge from Shinzo Abe’s shadow and step into his shoes will have a very narrow scope within which to move. This scope will be all the more limited since Mr. Abe is a leader of exceptional staying power and political longevity.

The leaders of LDP’s various factions will probably not support someone who can make as big an imprint as Shinzo Abe has.

Scenarios

The leaders of LDP’s various factions will probably not support someone who can make as big an imprint as Shinzo Abe has. While other strong leaders have emerged from such negotiations, like former prime ministers Kakuei Tanaka, Yasuhiro Nakasone and Junichiro Koizumi, the backroom dealing is most likely to produce one that will not step on too many toes.

Most importantly, the leader after Prime Minister Abe will have to focus on the domestic economy in Japan. Of the “three arrows,” two – monetary policy and fiscal policy – have reached their targets. On structural reforms, much remains to be done. Since Prime Minister Abe’s successor is unlikely to be a strong leader, those structural reforms will remain a far-off prospect.

Moreover, economic difficulties and a tilt toward populism have emerged in many established Western democracies. Japan has remained mostly free of such developments, bolstering the arguments of those who oppose far-reaching reforms.

After Prime Minister Abe, who has enjoyed an unusual amount of limelight, Japan will return to LDP politicians who lack charisma and fit the traditional profile of dull apparatchiks. This may not be bad for Japan, as the focus on Shinzo Abe’s personality and his historical “baggage” have kept Japan from building a more constructive relationship with its neighbors. This goes most notably for South Korea, where acrimony between Seoul and Tokyo has risen recently.