Japan’s mercantilism in the spotlight again

President Trump has been lenient in his criticism of Japan’s domestic market. If he wins a second term in office, he may change tack and slap tariffs on. President Trump has been lenient in his criticism of Japan’s mercantilism. If he wins a second term in office, he may change tack and slap tariffs on. ring new reasons to move in that direction.

In a nutshell

- U.S. displeasure over Japan’s mercantilism and its intricate barriers to foreign businesses is quietly shared in Europe

- Geopolitical instability and unfavorable demographics at home are prompting Tokyo to seek new business opportunities abroad

- For the strategy to succeed, Japan may need to undergo cultural change and open up its domestic market to foreign competitors

In Tokyo, much is being made of the special relationship Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe shares with United States President Donald Trump. On a personal level, the two leaders are said to have an exceptionally good rapport. This, however, does not mean that Japan is shielded from Mr. Trump’s pressure on the bilateral trade front. Much of his criticism of Japanese trade policy is justified. Moreover, it is echoed – behind closed doors – by the Europeans.

At the recent G20 summit in Osaka, the U.S. president humored his Japanese hosts. The Americans cooperated in crafting a joint statement, something they had abstained from during the G20 gathering one year earlier – however weak and vague that communique turned out to be. How little Mr. Trump cares about Mr. Abe’s feelings when he pursues his own policies, though, was shown in the U.S. president’s seemingly spontaneous decision to shake hands with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un at the border point of Panmunjom. It is no secret that Tokyo has been upset about being left entirely out of the loop when it comes to U.S. initiatives on the Korean Peninsula.

Japan’s vulnerability

On the surface, Prime Minister Abe can claim that he has had more personal interactions with President Trump than the chancellor of Germany or the president of France have had. Also, Mr. Trump’s rhetoric criticizing other countries for taking unfair advantage of U.S. markets has been recognizably less shrill in Japan’s case than the Europeans’. Still, this does not mean that, for example, Japan’s automobile industry is safe from the threat of American tariffs. There is only so much a personal rapport can accomplish when dealing with today’s White House. And when it comes to vital geopolitical issues, Japan is more vulnerable than major European NATO member states.

Japan will have an enhanced economic presence in India and South East Asia.

It is rather well known that Prime Minister Abe’s economic reforms, nicknamed “Abenomics,” have brought limited results (in large part due to Japan’s socioeconomic structural rigidities). However, one area of significant recent change in the government’s policy has not received enough attention in the outside world: Japan’s ramping up of overseas activities, notably in South East Asia and in India. Tokyo has recognized that it can at least partially compensate for the new uncertainties on the U.S.-Japanese front by engaging more with major Asian countries. China’s geopolitical ambitions and increased military presence in the South China Sea and, most recently, its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), have been wake-up calls for the Japanese.

Japan will have an enhanced economic presence in India and South East Asia, most notably in Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand. This way, Tokyo hopes to counter China’s massively increased overseas economic presence, particularly along the BRI. The 2016 establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), a forceful and innovative initiative from the People’s Republic of China to create a rival to the West-dominated Bretton Woods institutions and the Asian Development Bank (ADB), has motivated Tokyo to increase its engagement in the South and Southeast Asia region. Among the recent moves by the Japanese has been a substantial capital injection into the ADB. This comes at a time when leading Japanese companies are increasing their investments abroad in response to the aging population at home, which has resulted in shrinking or stagnant domestic markets.

Japan using its economic muscle is nothing new. As the world’s largest creditor, Japan is no stranger to huge outlays overseas. However, in a departure from Tokyo’s traditional reluctance to engage in political forays abroad, the island nation has started to strengthen its geopolitical stance under Prime Minister Abe. It sees Australia and India, in particular, as fellow democracies that have similar security interests to Japan’s. Mr. Abe has established a good personal rapport with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Difficult market

Japan had been very keen on the now-defunct Transpacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement. Prime Minister Abe had invested a lot of his political capital into the project, as it aimed to contain China’s rise in East Asia. Under U.S. President Barack Obama (2009-2017), the TPP seemed to evolve substantially, not least because the Japanese had been very accommodating. However, President Trump fulfilled his campaign promises and called off U.S. participation in the TPP as soon as he entered the White House. Washington has signaled since that it could return to the project, but it is too early to speculate on whether it will.

Facts & figures

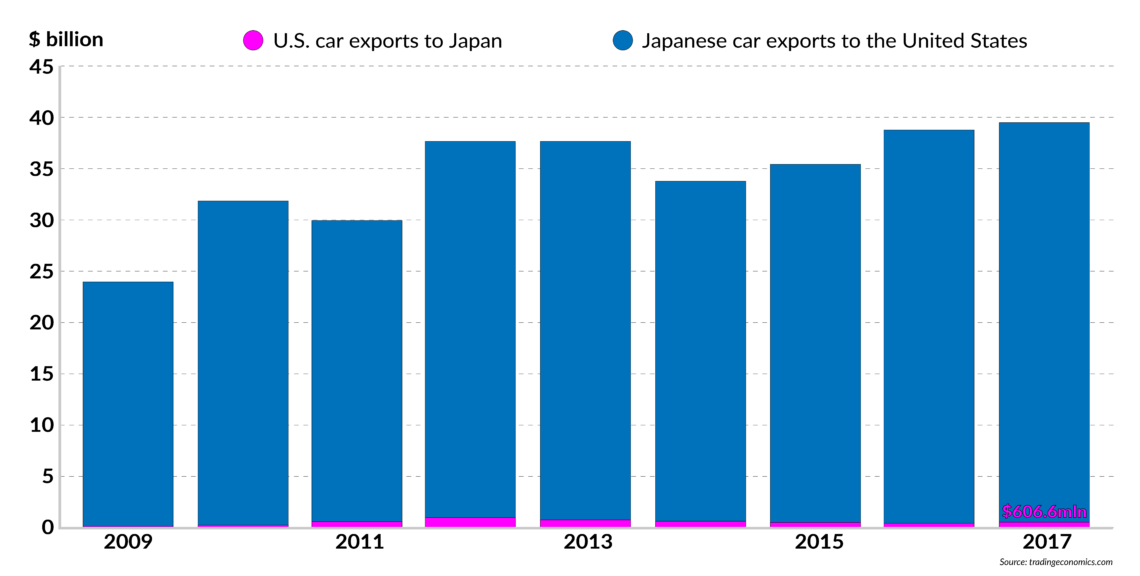

Lopsided U.S.-Japan trade in motor cars

When it comes to issues of free and fair international trade, Japan is vulnerable, as it does not measure up to the standards expected from a leading economic power. When it had to rebuild its industry from the tremendous devastation of World War II, Japan mostly followed the course chosen by China some two decades later. The focus was on copying Western industrial designs, producing the cheapest consumer goods for export and flooding world markets with these products. It was only in the 1970s that Japan’s rise as a significant technological power gained momentum. Today, of course, Japan is among the most innovative economies in the world.

A second trait that Japan’s economic modernization has in common with China’s is the focus on accumulating wealth by making sure that substantial trade surpluses bolster the foreign exchange reserves. For a long time, Japan was the world’s largest holder of foreign reserves. China overtook it in this respect only in 2006. It is fascinating for foreign visitors to learn that even today average Japanese consider securing economic independence and keeping national control over the country’s economy as matters of critical importance.

The Japanese corporate world is vulnerable to the charge of mercantilist practices.

Most foreign companies confirm that Japan is a tough market to enter and even more challenging to succeed in. Japanese consumers are extremely fashion conscious and trends can disappear as fast as they have emerged. There is also the Japanese bureaucracy, regulations and market structures that make it hard for foreign products and services to compete with domestic players. Japanese authorities may not establish customs barriers but, for example, the country’s wholesale trade system is so complex and firmly controlled by Japanese companies that hardly any foreigner has a chance to establish a foothold there.

Japan is an island nation with few natural resources. It needs to import all of the oil and natural gas it uses. Furthermore, it can only provide about 40 percent of its food needs through domestic production. This is particularly worrying to older Japanese, who see their country as threatened by foreign adversaries. Oft-heard complaints about “unpatriotic” consumers refer to the population’s changing eating habits. Instead of rice, young Japanese prefer pizza and pasta, products based on wheat that needs to be imported, to the detriment of the interests of the powerful lobby of rice farmers.

The Japanese corporate world, too, is vulnerable to the charge of mercantilist practices, be they open or hidden. Foreign companies find it next to impossible to acquire production facilities in Japan or take over Japanese companies. When it comes to foreign investment, Japan shows a balance in its favor with practically every industrialized country. It makes things no easier that Tokyo defends its mercantilist practices by claiming that they are an essential element of the societal structure of the country. Indeed, the mercantilist attitude belongs to the unique social contract that is at the center of Japan’s identity.

Depending on the longevity of the Trump administration, we may eventually witness a more targeted American attack on Japan’s age-old mercantilist ways. This would most certainly affect Japanese agriculture, one of its most protected economic sectors. It is also a sector where the effects of the demographic processes will be felt acutely in the not-too-distant future. Already today, the average age of a Japanese rice farmer is some 65 years.

Should Mr. Trump win a second term, he may harden his stance toward Tokyo.

If the long-term goal of American pressure is to pry open the Japanese economy, numerous reforms in economic structures beyond traditional agriculture would need to be instituted. The wholesale and retail trade systems require substantial change, not least in the interest of Japanese consumers who are regularly victims of price gouging.

Scenarios

The most likely scenario is that the pressure on Japan will intensify in President Trump’s probable second term. For now, he has too many trade battles on his plate and, bearing in mind the good relationship he enjoys with the Japanese prime minister, he may not want to open another front. Should, however, Mr. Trump win a second term, he may harden his stance toward Tokyo. Moreover, the Europeans have trade complaints about Japan, too, not dissimilar to those voiced in Washington. In any scenario, the great unknown is how China’s geopolitical position will evolve. If the military and security threats emanating from China increase, an open Western trade conflict with Japan will become less likely.

Even such a scenario does not mean, however, that Japan would be off the hook. It has an urgent need for reforms and opening to foreign competition in the corporate world. Recently, an affair involving Carlos Ghosn, a former CEO of Nissan Motor Company who was arrested in 2018 on charges of misuse of the firm’s assets, focused Japanese public’s attention on the issue of alleged abuses of one Western manager. However, more significant questions are looming about the problems of foreign management and foreign ownership in Japanese companies.

The record of mergers between Japanese and foreign companies is strewn with failures, most of them caused by cultural insensitivity. Increasingly, though, it is becoming clear that beyond understandable cultural factors, there is something seriously wrong with the Japanese corporate world. As the country is ever more dependent on overseas engagement, its cozy corporate world in which the locals deal exclusively among themselves and leave the foreigners out seems destined to come to an end.