Political change in uncertain times

In Latin America, a new electoral super cycle could dramatically change the continent’s political landscape and put authoritarianism back on the map. Several trends are emerging, most notably a departure from established parties.

In a nutshell

- A wave of political change is sweeping over Latin America

- Many countries are turning away from centrist candidates

- Widespread unrest could lead to political crises

The Latin American and Caribbean region is going through a new electoral super cycle. Between 2020 and 2024, all Latin American countries except Cuba are holding presidential and legislative elections. Nine countries are holding elections in 2021, with five – Chile, Ecuador, Peru, Honduras and Nicaragua – selecting presidents. Argentina, Chile, El Salvador, Mexico and Paraguay are electing congressional deputies, governors and mayors. Some 200 million voters are going to the polls this year.

This super cycle comes at a challenging time. The health crisis rages on in Latin America, which has 8 percent of the world’s population but over 20 percent of Covid-19 infections and about 32 percent of deaths. Lockdowns exacerbated the ongoing economic crisis. The Latin American economy contracted by 7 percent, and poverty is estimated to have increased by 19 million people. Governments have responded with countercyclical fiscal policy to support the poorest, with only modest success. And in parallel, the pandemic has aggravated the region’s long-standing political crisis of representation.

Surveys show growing discontent with politics and democratic fatigue running through Latin America.

Political instability has been worsening, especially with governments failing to secure vaccines rapidly and imposing lockdowns that greatly affected the population in middle-income countries. Moreover, according to the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), the measures have stirred unrest in the region. Surveys show growing discontent with politics and democratic fatigue running through Latin America.

Elections in the time of Covid-19

Ecuador

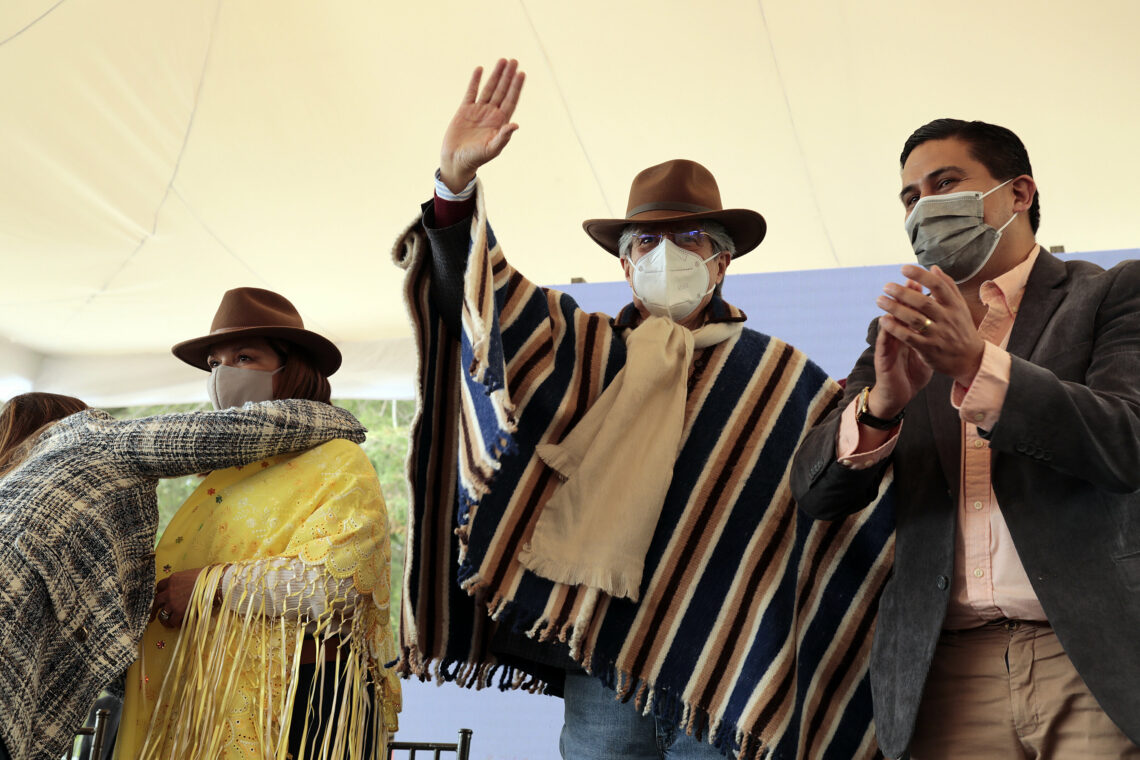

This past February, Ecuador held elections to replace President Lenin Moreno. The race was dominated by conservative banker and businessman Guillermo Lasso, indigenous leader Yaku Perez, and left-wing economist Andres Arauz – a protege of the long-reigning former President Rafael Correa, whose corruption conviction prevented him from running for vice president. There were 16 candidates in the race; Ecuador’s political parties are extremely weak, as in most other countries throughout the region.

In April, Mr. Lasso won the second round with 52 percent, marking the end of “Correismo.” Yaku Perez from the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities, who had arrived third in the first round, asked his voters to vote null. The resulting 1.8 million protest votes in the second round allowed Mr. Lasso to win the presidency, bringing the country from the left to the right side of the political spectrum. It was also the first time that the indigenous movement played the role of kingmaker. But the new president could struggle to implement reforms. There are currently 11 parties in the fragmented Congress, hampering governance.

Peru

During Peru’s presidential and congressional elections in April 2021, 16 political parties fell below the representation threshold. Pedro Castillo, a socialist schoolteacher and member of the Marxist Free Peru party, emerged from the depths of the Andes as an unknown indigenist candidate. With roughly 19 percent of the votes, he unexpectedly became president less than a year after appearing in the public eye. This type of election has become a trend in Latin America: a weak, independent candidate rises above the party system, which cannot answer people’s demands.

Chile

In 2019 Chile suffered its most severe political crisis since its return to democracy, shaking one of Latin America’s most stable and seemingly successful states. Massive protests led to the formation of a democratic and participatory constitutional convention to replace the current one, which dates back to the Pinochet dictatorship. Chileans were called to vote in four simultaneous elections on May 15 and 16: elections of the members of the Constitutional Convention, mayors, councilors, and the new position of governor. The elected 155 convention members are now debating the final document, which the public will ratify in 2022.

The problems that gave rise to the demonstrations of 2019 have not been solved but rather made worse by the pandemic. On November 21, the country will hold presidential elections unlike any since the restoration of democracy in 1989. Results will show whether the convention appeased the unrest of 2019, or whether it will kick off a process of radical change. Whoever is elected will have to promulgate the new constitution, but with a divided congress and an atomized political scene, legislating will be difficult.

Nicaragua

Nicaragua went from a right-wing dictatorship under Anastasio Somoza Garcia, followed by a brief democratic period, to a left-wing autocratic government under Daniel Ortega. The Nicaraguan president has been in power for more than 30 years in total (from 1979 to 1990 and then from 2007 to today), and he is the longest-serving Latin American head of state. In 2017, he appointed his wife Rosario Murillo as vice president. More than a dozen opposition candidates are in prison, and this November’s presidential elections are broadly believed to be little more than a show staged by the ruling family.

Mexico and Argentina

Last June, Mexico’s legislative elections punished the ruling party in Mexico City and opened the door to the opposition, especially the well-established center-right PRI and PAN parties. Argentina is also facing part-time legislative elections on November 14. During the September primaries, the ruling Peronist party suffered a severe blow by losing 1.2 million votes compared to 2019 – additional proof that the region is seeing a trend toward change.

This left-right pendulum shows a continuing trend toward populism due to disillusionment with political moderates.

Brazil. The Brazilian presidential elections will be held in 2022. President Jair Bolsonaro came to power with enormous popular support (55 percent of votes) in 2019, but his situation has greatly deteriorated. He currently faces multiple petitions for impeachment in Congress and harsh criticism for his management of the pandemic – Brazil has the second-highest Covid-19 death toll in the world.

Scenarios

Populism, polarization and a possible turn to the left

The region’s outlook for democracy looks worrying, even if democratic elections are taking place. Nicolas Maduro has established a dictatorship in Venezuela. Daniel Ortega, backed by Cuba, is ruling an autocracy in Nicaragua. And now, Latin American voters are turning to populist candidates with little commitment to the balance of powers. In parallel, moderate centrist parties are weakening or collapsing. This is the case in Argentina, Ecuador and Peru, where – for the first time – extreme libertarian candidates fared well in the midterm primaries.

Some countries have seen a swing to the left, like Peru and Chile. Some others shifted to the right, like Ecuador, and Brazil under the ultranationalist President Bolsonaro. Uruguay also elected the conservative National Party after 16 years of leftist rule. What all these changes have in common is extreme political polarization and rifts in the center. This left-right pendulum in Latin America’s political landscape shows a continuing trend toward populism due to disillusionment with political moderates rather than an oncoming pink tide of socialist governments.

Party fragmentation and weak presidentialism

Latin America’s list of extremely weak presidents has grown longer: Sebastian Pinera (Chile), Alberto Fernandez (Argentina), Ivan Duque (Colombia), and, more recently, Guillermo Lasso (Ecuador) and the five presidents that have ruled Peru since 2016. Midterm elections have also eroded Mexico’s presidency, and the approaching presidential elections in Chile and Brazil will most probably weaken their presidents’ mandate as well. These politicians often lead parties that have so little support that, once in power, they find themselves with no strength and few allies.

Whether on the right or the left, the election of populist candidates may further undermine democracy in the region. This process could create a breeding ground for authoritarian presidencies, possibly increasing militarization. Some countries have already granted the military exceptional powers to maintain law and order during the implementation of extreme lockdowns and curfews, for example.

Exacerbation of political discontent and social unrest

In Latin America, the underlying causes of social unrest have grown more pronounced. Many countries will probably experience turmoil in the coming months and years due to the pandemic worsening the already severe economic inequalities. Covid-19 has pushed 4.7 million people out of the middle class and into poverty or precariousness. The situation was made especially dire because of the slow vaccination rollout and exceptionally tough lockdowns.

With so many elections taking place, voters will be able to express their frustrations. Going to the polls may help lower tensions. But at the moment, citizens are showing their distrust in institutions and dissatisfaction with how governments have managed the pandemic. The social mobilization of late 2019 – significant in Chile, Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia – is beginning to reactivate after being interrupted by the pandemic. Although each country’s situation is unique, the toll of the coronavirus combined with political crises could become fertile ground for the Latin American people to take to the streets.