Latin America’s difficult outlook

Economic downturns, political mismanagement and natural disasters have raised poverty rates and inequality in Latin America, creating a dire outlook for 2021. Populist politicians could benefit from the growing discontent.

In a nutshell

- The pandemic has set back socioeconomic progress in Latin America

- More left-leaning populists could gain power in several countries

- At odds with China, the U.S. will face difficulties in promoting its agenda

This GIS 2021 Outlook series focuses on the opportunities that stem from the upheaval of the past year.

The outlook for Latin America in 2021 and beyond leaves little room for optimism. While the region is home to less than 8 percent of the global population, it accounts for over 30 percent of confirmed Covid-19 infections and deaths, with the highest rates in Mexico and Brazil.

Disruptions due to the pandemic will take years to mend. The International Monetary Fund projects that it will take the region four years to return to – already sluggish – pre-pandemic levels of economic growth. The World Bank predicts that the region’s gross domestic product will grow by 3.7 percent in 2021, far from making up for the 7.7 percent contraction in 2020.

Economic shutdowns have dramatically increased poverty.

Emerging economies grew by 4 percent in 2019, while Latin America and the Caribbean grew by 0.1 percent, even without factoring in Venezuela’s dire recession. In the meantime, the most vulnerable citizens will suffer – inequality is set to worsen.

Poverty on the rise

The economic shutdowns and associated downturns have dramatically increased poverty throughout the region. Over 22 percent of Mexico’s 129 million people now live on less than $2 a day, an increase of more than 6 percent from 2019. In Colombia, this vulnerable demographic grew by 4 percent of the population, and now includes 14.3 percent of its 51 million citizens.

Overall poverty rates increased as well, to 51 percent of Mexicans and 34 percent of Colombians. Actual rates could be higher, as many in the region are employed in the informal sector. These changes portend disruptions for the region.

In places like Central America’s Northern Triangle region, the most conspicuous and enduring development is migration. In 2021, it will be driven by several factors, including displacement due to the late 2020 hurricanes, minimal government stimulus spending, low confidence in leaders and expectations that the United States will ease its immigration policies. Soon, large caravans may again make their way to U.S. borders. Venezuela’s worsening situation and the regime’s mismanagement of the pandemic has also increased outbound flows of refugees to neighboring countries.

Facts & figures

Criminal organizations

With governments distracted by the pandemic, transnational criminal organizations have capitalized on the rising poverty. Production of synthetic opioids is back to pre-pandemic levels, after a brief slowdown due to lockdowns in China and India that limited the availability of chemicals needed to produce them. Prices for these dangerous drugs, however, have increased.

Some criminal organizations in Brazil, Mexico and Central America have even taken over the state’s role in handing out food, providing sanitation supplies and enforcing curfews. In turn, citizens, already displeased with their government’s inability to contain the virus and provide for their well-being, are further losing confidence in the state. Numerous general and legislative elections will take place in 2021, and the same antiestablishment fervor that fueled regional protests in 2019 will undoubtedly influence these upcoming races.

Socioeconomic regression

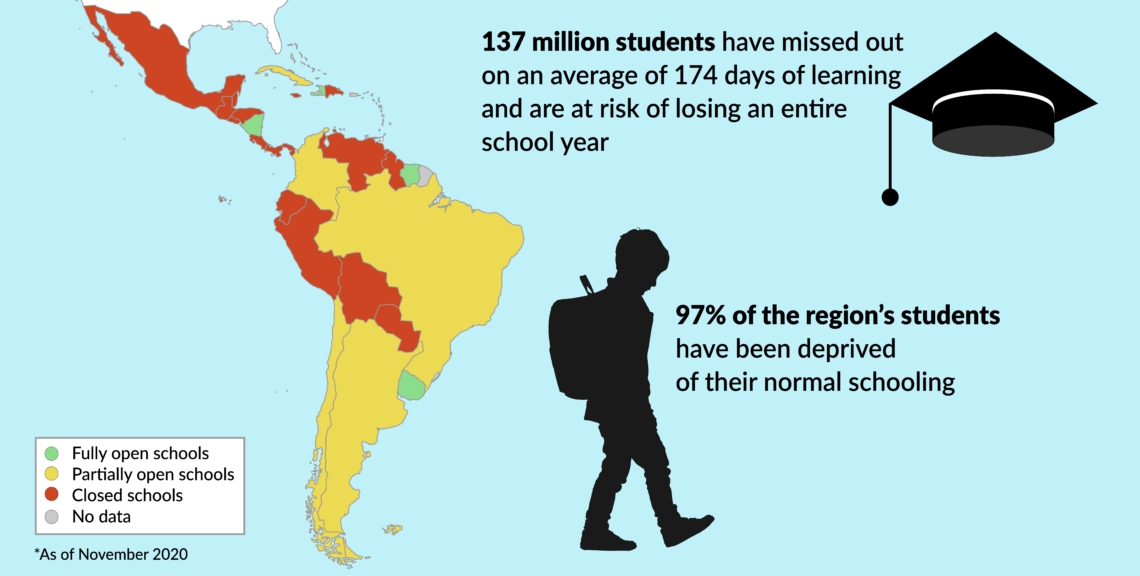

Widening income gaps, rising levels of inequality and a growing sense of desperation will play key roles in these elections. Public concern over issues like Latin America’s poor public education system has reached new heights. According to the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), public schools in Latin America were closed for 174 days in 2020 – four times more than the global average. Some 97 percent of the region’s children have been deprived of normal schooling. While in much of the developed world students are receiving instruction from home, 50 percent of school-aged children in Latin America do not have access to high-speed internet. The availability of high-speed mobile technology is limited as well. Less than 50 percent of the region’s population has access to 4G.

A single year’s lack of schooling will likely wipe out years of educational and socioeconomic advances for the region’s most vulnerable – a catastrophic outlook for Latin America in 2021. The secondary school graduation rate among students whose parents graduated from secondary school themselves is due to drop by 15 percent. Among kids whose parents did not obtain a high school diploma, the decline will be 20 percent.

Inoculation campaigns in Latin America are still months away from starting.

The drop in education rates has made more people susceptible to influence from gangs and criminal organizations. The risk is especially great if their caregivers are having trouble making ends meet. The Coalition Against the Involvement of Children and Youth in the Colombian Armed Conflict (COALICO) reported that 190 youths were recruited by illegal armed groups from January to June of 2020, a sharp increase from 38 in the previous year.

All the above-mentioned factors will widen the gap between the rich and poor, a phenomenon that will become painfully clear during the vaccine distribution process. While most developed nations have begun their vaccination rollouts or will soon do so, inoculation campaigns in Latin America are still months away from starting. The Economist Intelligence Unit predicts that Covid-19 vaccines will not be widely available in the region until mid-2022, and perhaps as late as 2023. The delay could lead to widespread discontent, as the region’s poor have already suffered immensely from the health and economic effects of the pandemic.

Governments, however, cannot spend on programs to alleviate that suffering (much less expand opportunity), due to a lack of income. To avoid financial collapse, some are attempting to reopen their economies.

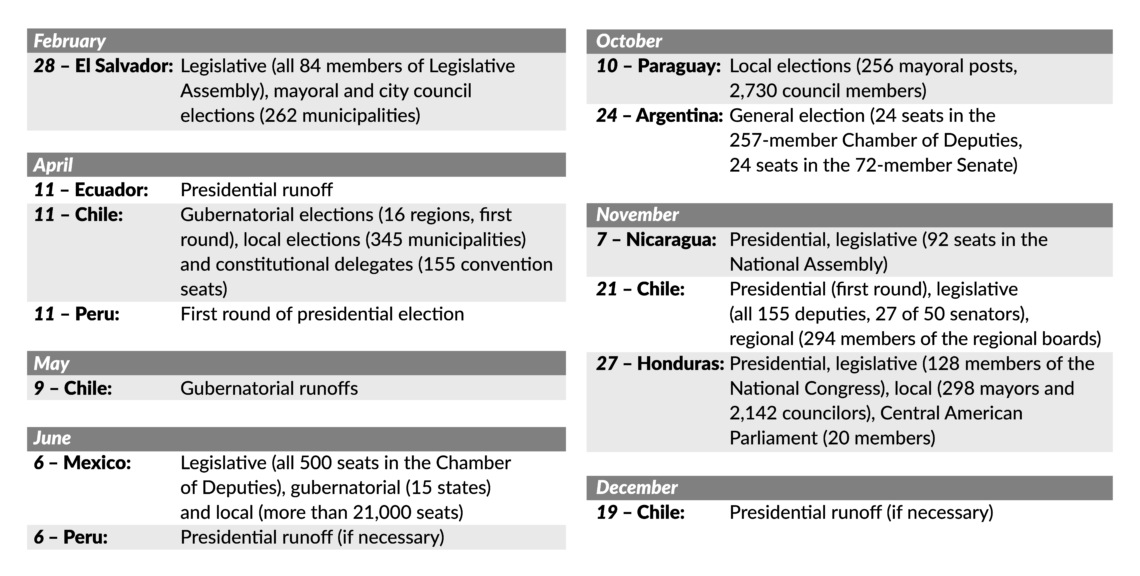

Super election cycle

Over the next year, there are five presidential, eight legislative, and numerous gubernatorial and local elections. Chile will also vote on representatives to a constitutional convention. This super election cycle will put pragmatic policymaking to the test, as ruling parties will be less inclined to push fiscally conservative policies.

Anti-incumbent sentiment and rising support for populism have gripped the region. Ecuador is a prime example of the changing political winds. President Lenin Moreno has chosen not to run for office again. In the first round of voting last week, Andres Arauz, once a minister in former President Rafael Correa’s government, won the plurality of votes. He ran on promises of repealing President Moreno’s reform-minded agenda.

Facts & figures

Later this month, El Salvador will elect a new Legislative Assembly and local officials. Though he is controversial internationally, President Nayib Bukele is one of the most popular leaders in the region. His populist political movement is still new enough to ride the anti-incumbent wave, and his party will almost certainly win control of the legislature. Peru will hold elections for president and the legislature in April but widespread apathy over a series of recent political crises has left over 30 percent of the population ambivalent about whom to support or whether to vote at all.

In June, Mexico’s legislative and gubernatorial elections are poised to cement President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador’s influence over his country’s politics. The traditional two-party system seems to have run its course, at least for the near future. Despite President Obrador’s mishandling of the pandemic and the economy, his party – the National Regeneration Movement, or MORENA – still dominates the Mexican political scene.

In Argentina, President Alberto Fernandez’s unpopularity and divides within his coalition could result in even more leftist politicians gaining prominent positions. That development would strengthen his Peronist vice president, former President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner. In October, the country’s legislative and provincial elections could have far-reaching implications.

The pandemic has disrupted traditional commitments to political parties.

Elections in Chile – for the presidency and all the way down to local positions – will prove a major test for the government in November. For the 78 percent of Chileans who voted in favor of drafting a new constitution, the most crucial choices are the 155 members of the constitutional convention. Honduras’s general elections will also occur that month. Even though President Juan Orlando Hernandez is unpopular and faces accusations of drug trafficking by U.S. authorities, his party’s candidate is expected to win the election.

Nicaragua will hold a general election in November, too. Leftist authoritarian President Daniel Ortega is expected to continue governing the country he has run nearly uninterrupted since 1979. His party controls all the various levers of power. Following the devastating 2020 hurricanes, he now has access to vast amounts of international assistance, with which he will continue to buy the support of his impoverished citizens. After years of fracturing and politically targeting the opposition, his opponents lack the ability to mount a viable offensive against him.

The pandemic has disrupted traditional commitments to political parties and ideological beliefs, blurring the lines on the political spectrum. Conservatives have traditionally opposed large government stimulus and bailout expenditures, but now see them as a means to keep economies going. At the same time, Mexico’s President Lopez Obrador, who some would categorize as a leftist, has implemented the region’s most fiscally austere pandemic response.

Scenarios

The administration of new U.S. President Joe Biden has indicated that it will continue to prioritize to improve the outlook for Latin America in 2021 and beyond. It has proposed a $4 billion development package for Central America’s Northern Triangle region and has promised to engage more in multilateralism, as well as focus on climate change, human rights and anti-corruption efforts. The U.S. will keep up pressure on Venezuela for as long as there is strong bipartisan consensus for restoring democracy there. The tactics in applying that pressure, however, will almost certainly differ from those of the Trump White House.

The U.S. will also retain its support for pushback against China’s rapid regional expansion, which is undermining democratic norms and sovereignty. Many Latin American countries are scheduled to begin their 5G spectrum auctions in 2021, for which controversial Chinese firm Huawei will be an important bidder.

The Biden administration will face difficulties in promoting its climate change agenda in Latin America, which is dependent on hydrocarbons and faces tight fiscal constraints. President Biden has said he intends to cooperate with China where possible – but doing so will make it difficult to counter Beijing’s aggressive behavior. Moreover, his commitment to multilateralism will be challenged by the need to advance U.S. interests.