A war in metamorphosis

In October, the key domestic actors in Libya’s conflict resumed political dialogue. Three factors have helped this process: the military setback suffered by Khalifa Haftar, the prolonged cease-fire, and the mounting street protests as Libya sinks into chaos.

In a nutshell

- A cease-fire has taken hold in Libya's conflict

- Diplomatic efforts are underway to lift the oil blockade

- No real breakthrough for a reunification of the country is in sight

Peace remains as elusive as ever in Libya’s conflict. However, the splintered country’s conflict is undergoing a metamorphosis.

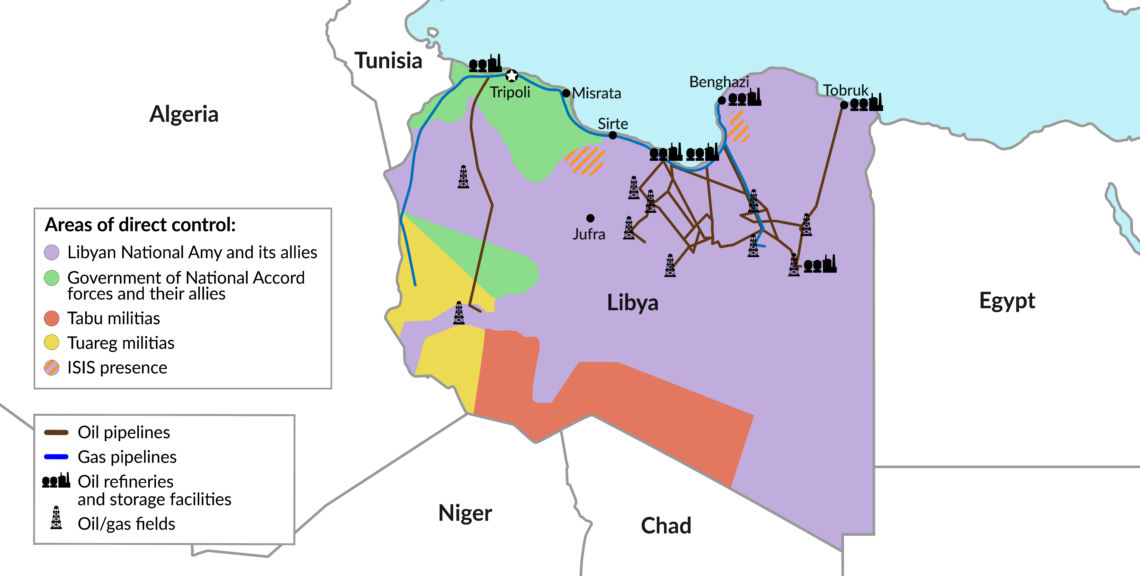

Libya’s latest conflict has been going on for over a year. It broke out in April 2019. Khalifa Haftar, commander of the Libyan National Army (LNA) based in Cyrenaica, sought to capture the western part of the country and the capital of Tripoli. The latter is the seat of the United Nations-backed Government of National Accord (GNA), led by the moderate though ineffectual Fayez al-Sarraj. The advancing LNA forces reached the outskirts of the capital, laying siege to the city. But, in March 2020, Turkey’s decisive military intervention tipped the scales in favor of the Tripoli government.

The Haftar forces were pushed back and a military stalemate ensued. It was formalized on October 23, when a national cease-fire was signed by representatives of the Libyan antagonists in the UN’s Geneva headquarters.

Field Marshal Haftar seems to have lost much of his appeal. Also, it is not clear how much support he still has from his key supporters, the United Arab Emirates, Russia, Egypt and, to some extent, France.

Facts & figures

Domestic woes

Libyan leaders – both in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica – are struggling to manage the bankrupt state and the mounting anti-corruption protests on the streets. On top of that, the pandemic has been claiming its toll: on November 1, alone, 62,045 Libyans were reported infected with SARS-CoV-2 and 871 died of the illness. And these figures probably do not show the real scale of the tragedy since testing is inadequate and the country’s hospitals are short in basic supplies such as ventilators and intensive care units.

Libya sits on the largest proven oil reserves in Africa. However, earlier this year Field Marshal Haftar’s forces choked off key pipelines and terminals, shutting down the most important fields in Libya’s western part. His plan was to bring the Tripoli-based government to its knees. The blockade has caused some $10 billion revenue loss and pushed the Libyan rentier state to the brink of economic collapse. Since 2013, oil blockades have cost the country an estimated $180 billion in lost revenue.

There is no agreement on how the divided nation’s parts should split the oil revenues.

Now that the LNA offensive has been thwarted, complicated efforts are underway to end the crippling blockade. Last September, for example, GNA Vice Premier Ahmed Maiteeq met one of the field marshal’s sons, Khalid Haftar, in the Russian resort of Sochi to discuss solutions.

The goal is to ramp up oil production from current levels, around 100,000 barrels per day, to more than a million barrels per day, which would fund state salaries and most essential services – above all, electricity. However, there is still no agreement on how the divided nation’s two parts should split the oil production revenues. For now, the proceeds are frozen in a Libyan Foreign Bank account controlled by the country’s central bank (which broke up in 2014 along Libya’s broader fault lines into Tripoli and Benghazi branches).

External actors

On September 30, 2020, the UN registered the Memorandum of Understanding signed in November 2019 between Turkey and the Libyan GNA “on delimitation of the maritime jurisdiction areas in the Mediterranean.” However, a group of European ambassadors to Libya rejected it on October 10, claiming that the document “does not comply with the Law of the Sea and cannot produce any legal consequences for third states.”

October 2 brought another important development for the region: the foreign ministers of Italy and Turkey met in Rome to discuss national agendas, Libya and the Eastern Mediterranean. Simultaneously, the EU announced that Ageela Saleh, head of the Libyan Parliament based in Tobruk (the House of Representatives, HoR), and Nuri Abu Sahmain, former head of the General National Congress (GNC, not recognized internationally), were no longer subjected to EU restrictive measures – travel bans and assets freezes. The same day saw the delegations of the HoR and the Tripoli’s High Council of State participating in the second round of the Libyan dialogue sessions in Morocco. (The first round was held at the beginning of September; the dialogue stems from the first Berlin Conference of January 2020.)

The two delegations are reportedly working in good spirits and the event has the full support from the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL). The process owes a lot to the involvement of the mission’s acting head, Stephanie Williams, and a few countries, including Italy.

The head of U.S. Africa Command and American Ambassador to Libya have intensified their activity.

Three factors have helped move things along: the prolonged cease-fire; the military setback suffered by Field Marshal Haftar and the mounting public protests throughout Libya.

Morocco is not the only Maghreb country wishing for Libyan stability. For example, Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune declared that polarized Libya needs elections based on institutions and a new, better-balanced constitution to find its way out of the crisis. In practical terms, technicians from the Algerian utility company Sonelgaz are helping Libya’s General Electricity Company deal with constant blackouts.

On the other side of the ocean, the United States is displaying renewed interest in the Libyan situation. General Stephen J. Townsend, the head of U.S. Africa Command, and American Ambassador to Libya Richard Norland have intensified their activity and coordinated with Stephanie Williams to involve each of the actors operating on the Libyan chessboard. Ambassador Norland, for example, recently held discussions with the chief of Egypt’s General Intelligence Service (GIS), Abbas Kamel, in Cairo, on maintaining the cease-fire in Libya.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has also bitterly observed that violations of the Security Council’s arms embargo by the several countries that continue to deliver military support to the combatants “are a scandal and call into question the basic commitment to peace of all involved.” In the last few months, foreign deliveries of weapons have never stopped.

Good intentions coalition

Nevertheless, the “coalition of good intentions” pressed ahead. On October 5, Mr. Guterres and Germany’s Foreign Minister Heiko Maas cochaired a high-level meeting on Libya. It was attended by ministers and representatives of the first Berlin Conference in January 2020.

The conference generated a list of 52 recommendations intended to help establish a cease-fire, stop the flow of weapons and fighters being brought into the country, persuade the quarreling Libyan actors to engage in a political process, bring the transition period to an orderly conclusion and organize an election. None of this materialized.

The latest conference, taking place on the sidelines of the 75th UN General Assembly, ended up with the same agenda with one important addition: the extension of UNSMIL’s mandate for one more year. A new coordinator was proposed to manage the day-to-day issues, while the next special envoy would concentrate on political strategy.

Then, on October 23, an official cease-fire was signed during the Joint Libyan Military Commission talks. The agreement calls for a truce, the withdrawal of all mercenary troops from the country and the organization of a joint military force to identify, disband and bring all Libya’s militias back into the civilian or military national fabric. It also stipulates the reopening of the oil wells and the Libyan regions’ transportation routes. The deal has stirred much excitement among politicians and the international community, but analysts do not share that enthusiasm.

Libya’s conflict has become another contest field for the historical rivals in the region, Moscow and Ankara.

Europe lacks a unified strategy for the Libyan crisis, as recent conferences have amply demonstrated. By 2019, the EU had left a good part of Libya wide open to other players – Turkey and Russia. This alienated the Libyan population, which felt betrayed by the West.

Meanwhile, the tension in the Eastern Mediterranean basin is rising because of the maritime dispute involving Greece, Cyprus and Egypt (backed by France) on one side, and Turkey on the other. The contest is over the seabed drilling rights in overlapping exclusive economic zones claimed by these countries. The EU has been trying to defuse the conflict diplomatically, but with no significant results so far.

Brussels is divided over too many issues, so Libya’s conflict has become another contest field for the historical rivals in the region, Moscow and Ankara. As a result, these two capitals will now influence the African country’s future. The Europeans’ latest idea, to dispatch a 5,000- to 10,000-member contingent of European military observers, is unlikely to make a difference. The military contingent idea is neither new nor bad, however. It was suggested already two years ago in a Brookings Institution’s report for U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis. The authors recommended a large UN unit composed of a mix of Muslim armies from the Asian continent.

The rationale is that Libyans have been incapable of reaching a peaceful solution only by themselves for nearly a decade. The militias need to be brought under control and disarmed forcefully, as the weapons are their ticket to economic gains and higher social status. Europe’s policymakers tend to oversee these aspects of Libya’s conflict.

Scenarios

The peace talks in Geneva between the GNA and LNA, both weakened by domestic turmoil but backed by foreign powers, are highly unlikely to follow through on the October 23 cease-fire and produce a lasting breakthrough for Libya. The two factions have been waging war against each other since 2015 and neither they nor their backers are ready to change tack. Their interests remain divergent.

Only marginal progress, nibbling on the edges of problems, seems possible in Geneva at the moment. The crucial challenges, such as the disarmament of militias or the creation of a unified national army, could only be tackled with massive injections of foreign assistance and an external UN military contingent.

A complete failure of the Geneva negotiations is possible, but rather not in the short term. The states engaged in Libya want to maintain the appearance of being committed to peace, at least for now. As for the internal actors, namely the tribal leaders and, above all, the militia leaders, the issue is more complicated. Without a common enemy to fight, the militias, especially in Tripolitania, could engage in fratricidal clashes, destabilizing the entire country.

The chances that the EU will organize a European contingent are, practically speaking, null. To make it a reality, European countries would need to put aside their particular national objectives and create a common strategy for the Libyan file. Instead, Europe’s leaders seem happy to partake in international gatherings that lead nowhere.

In theory, it is within the UN’s powers to create, in cooperation with the U.S. – still seen in Libya as an impartial player – an international military mission there. A Muslim contingent could be used and the foreign states engaged in Libya could be given new roles in stabilizing the country – in essence, transformed from “bad guys” to “sheriffs” accountable for their actions at the international level.

However, today, any scenario in which a coordinated international action leads to a breakthrough in Libya seems doubtful. External and internal players continue to compete and pursue diverging interests. They are most likely to stick to their guns and predatory strategies in the foreseeable future.