The future of LNG for Europe

LNG is undergoing a production boom worldwide, mostly driven by the industry’s rapid growth in the United States. It could have profound effects on Europe, which has already become the largest buyer of American LNG. As a result, major changes are coming in the global gas market, as countries like Russia and Qatar jockey to compete.

In a nutshell

- Globally, LNG production and exports are rising fast

- The phenomenon could drastically alter the European gas market

- Russia is maneuvering to maintain and grow its market share in Europe

- The U.S. and other LNG exporters are cooperating to break Moscow’s grip

Although the United States only began exporting liquefied natural gas (LNG) in February 2016, it now sends the fuel to 33 countries worldwide. With the globe’s most efficient and competitive natural gas industry, the U.S. is poised to become the largest LNG exporter by 2025 – perhaps even earlier. The industry there benefits from an overhauled regulatory environment and the discovery of a huge new oil and gas field last year. American LNG exports (along with increased capacities in Qatar, Australia, Russia, Canada and other countries) have the potential to disrupt global gas trade patterns and dramatically transform the European market over the next two decades. They could also reduce Europe’s dependence on Russian gas, even as Moscow increases subsidies for gas exports to Europe.

Germany’s insistence on moving forward with the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline has created friction not only within the European Union, but also in transatlantic relations with the U.S. President Donald Trump has criticized Germany for being “captive” to Russian gas exports (an important source of income for Russia’s budget and funding for its military operations in Ukraine and Syria), while at the same time expecting the U.S. to defend Europe against Russia. Some in Germany counter such criticism with the accusation that Washington’s motives are purely economic: it wants Europe to buy more American LNG.

In recent years, the EU has expanded its LNG import capacity by more than 200 billion cubic meters per year (bcm/y) with the construction of 24 import terminals. The bloc considers LNG important for keeping its gas import portfolio diversified. In contrast, Germany, the largest gas market in Europe, has no LNG import capacity. After China and Japan, it is the third-largest gas importer in the world, but it is the only one in the top 10 that does not directly import LNG. Germany can only indirectly receive LNG deliveries from terminals in neighboring countries – the Netherlands (Gate), Belgium (Zeebrugge) and France (Dunkirk) – via a well-connected Western European pipeline network. In this context, many have questioned whether it makes commercial sense to build new German LNG import capacity. After all, less than 40 percent of the EU’s total LNG import capacity is currently being used.

LNG investments in Germany make strategic sense.

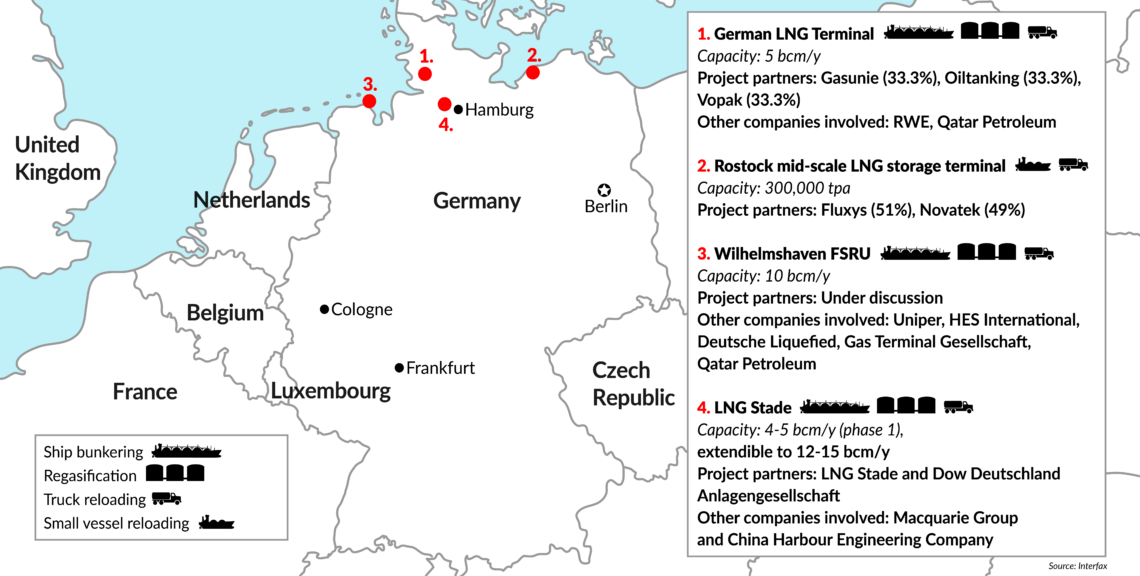

Instead, the idea of land-based LNG import infrastructure, or smaller-scale shipping terminals (so-called floating gas storage and regasification units, or FSRUs) is gaining ground in Germany. The concept is appealing, as LNG’s much smaller environmental footprint is making it an increasingly popular choice for bunker (ships) and trucking fuel over other petroleum-based products. Moreover, the EU recently agreed on a target of lowering carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from trucks by 15 percent from 2019 to 2025. There are also EU subsidies to be had for LNG infrastructure and maritime shipping projects that Germany would not like to miss out on.

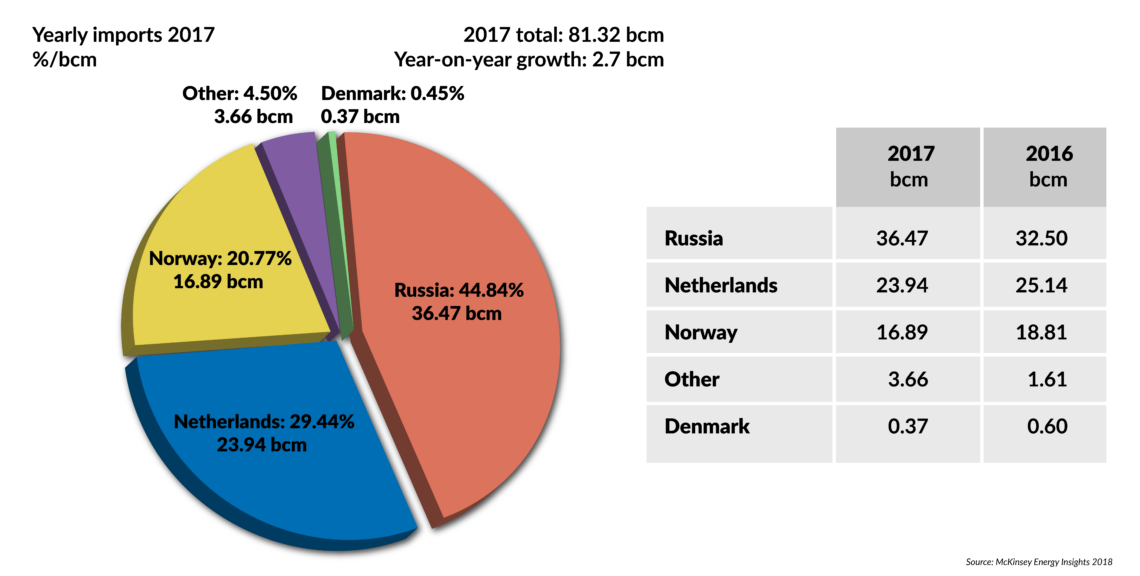

Such investments make sense from a strategic standpoint as well. Gas production is declining in Germany and the Netherlands (output from the Groningen gas field has fallen sharply). Yet, the resource is seen as “bridge fuel” to help Germany guarantee baseload power supply as its Energiewende policy moves production away from nuclear and toward renewables. The strategy has made Germany even more dependent on supplies from Russia. Last year, Russian gas accounted for 50 percent of all of Germany’s gas imports – up from 45 percent in 2017. And this all before Nord Stream 2 comes on line. In the coalition agreement signed by Germany’s governing parties in March 2018, there was a specific reference to “making Germany a location for LNG infrastructure.” Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) party insisted on such phrasing.

Currently, four LNG import infrastructure projects are being planned in Germany. Final investment decisions (FIDs) for all of them are expected for the second half of 2019.

Facts & figures

Germany's planned LNG projects

The U.S. is now a net exporter of oil and gas. American LNG exports already play a critical role in balancing worldwide LNG markets, while U.S. producers’ flexibility in terms of destinations and contracts has greatly influenced pricing. But can the new LNG wave really help Europe significantly reduce (ostensibly cheaper) gas pipeline imports from Russia?

The European gas market faces three key questions. First, how much LNG will Europe import from the U.S., Qatar and other countries to counterbalance its dependence on Russian gas? Second, will the price of heavily subsidized Russian gas be the only (or primary) criterion used by Europe to select gas suppliers? And third, will Russia reduce its pipeline deliveries to Europe or instead try to maintain market share and risk undercutting gas prices?

Russian moves

Germany’s growing interest in LNG imports is in line with global trends. The number of LNG importing countries has continuously increased, reaching 42 in 2018, compared with 34 in 2015 and just nine in the 1990s. A new, big wave of LNG export capacity will come on line this year. U.S. LNG exports have mostly shipped to Asia due to higher gas prices and profits compared with Europe. Also, higher-than-expected LNG imports in Asia (mostly in China) and delays in completing some new LNG projects (mainly in Australia) have made it more profitable for American producers to ship across the Pacific. A gas price war in Europe between Russian pipeline supplies and U.S. LNG has not yet materialized.

The shale gas revolution in the U.S. and the concurrent uptick in technological innovation for LNG has transformed the global gas market, slashing Russia’s gas export revenues and forcing its gas companies to renegotiate contracts with much shorter and more flexible terms. Still, Russia holds a dominant position in many markets in Europe, even despite efforts to diversify supply and enhance energy security, including the creation of the Southern Gas Corridor, the construction of gas interconnectors, the implementation of reverse-flow capabilities and the adoption of Europe-wide regulations. Eleven EU member states relied on Russia for more than 75 percent of their total natural gas imports in 2018.

While Poland and the Baltic states have tried hard to diversify their gas supplies, many other EU governments (including Germany) still choose the short-term benefit of cheaper Russian gas over long-term energy security and geopolitical stability.

Russian gas has a low break-even price of about $5 per million British thermal units (mbtu), compared with $6-7.70 per mbtu for American LNG. But if the U.S. cannot export enough LNG to Asia, it might be willing to sell LNG at levels close to $5 or $6 per mbtu in Europe, using it as a “sink market,” especially given its existing hubs with spot market prices and huge unused underground storage capacity (for example, in Ukraine). In this case, Russia might be forced to raise subsidies and lower prices even further. Doing so would come at a heavy cost with its economy groaning under the weight of Western sanctions.

Russia hopes to increase its total LNG export capacity from 29 mtpa in 2019 to more than 80 mtpa by 2035.

In any case, Russian LNG exports to Europe look set to rise, with several large investments due to increase production. This year, the Russian gas firm Novatek will make a final decision on its $27 billion Arctic LNG 2 project in Siberia. Gazprom and Shell have signed a memorandum of understanding for cooperation on the Baltic LNG project in the Russian port of Ust-Luga in the Leningrad region. This facility would have a capacity of about 10 million tons per annum (mtpa). Gazprom also plans to deploy its first FSRU at the port of Kaliningrad. Russia hopes to increase its total LNG export capacity from 29 mtpa in 2019 to more than 80 mtpa by 2035, becoming the world’s third-largest LNG exporter.

Facts & figures

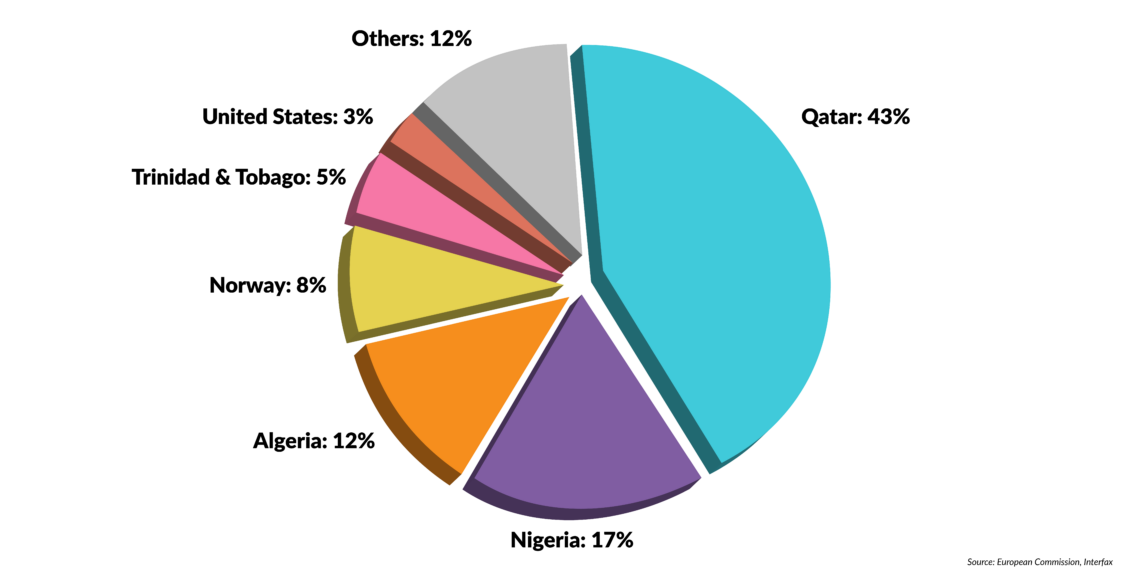

Europe's LNG suppliers

Q3 2018

Since November 2018, U.S. LNG exports have increased to new record highs. By the end of this year, they are expected to rise to more than 90 bcm from 50 bcm in 2018. Northeast Asia and Latin America received 75 percent of U.S. LNG cargoes in 2018. Despite the U.S.-China trade conflict, China was the third-largest importer of U.S. LNG last year, after Japan and South Korea. Current estimates put the rise in Chinese demand for imported LNG at between 155 and 215 bcm/y by 2035. However, if the country’s switch from gas to coal outpaces growth in domestic gas production, the demand for LNG imports could even exceed 300 bcm/y. If that happens, gas prices in Asia may again be far higher than in Europe, making it more profitable for American producers to turn their attention to the Far East.

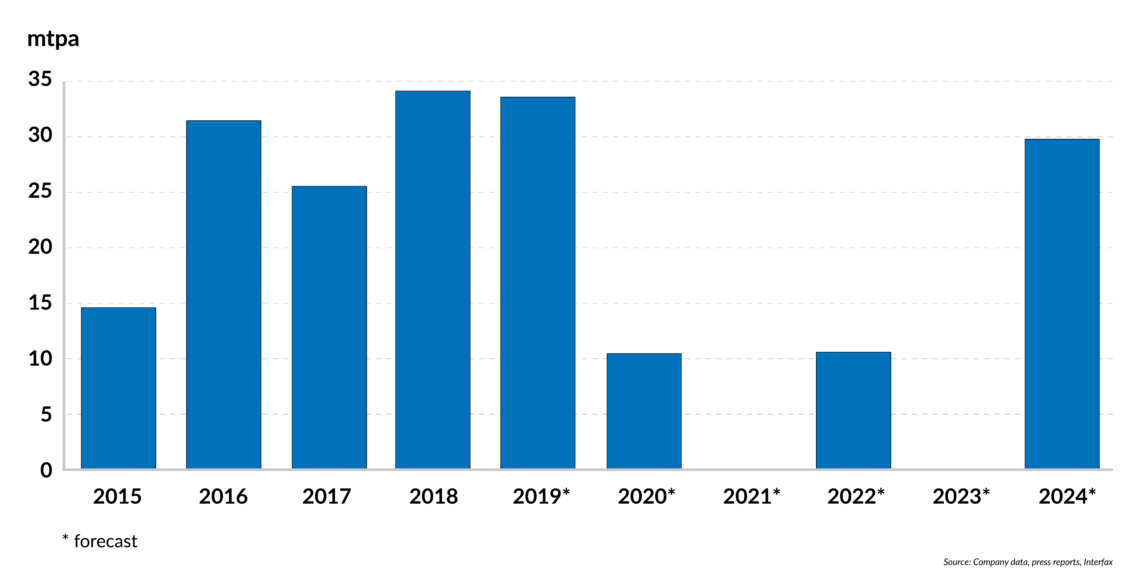

LNG boom

This year, an additional 33.5 mtpa of LNG export capacity is scheduled to be brought on line, mainly from new liquefaction projects in the U.S. portion of the Gulf of Mexico, as well as new supplies from Australia and Argentina. Last year, export capacity rose by 34.1 mtpa. Global LNG production could expand by as much as 11 percent, reaching 354 mtpa in 2019 and 384 mtpa in 2020.

Facts & figures

New LNG export capacity added worldwide

While Australia could overtake Qatar as the world’s largest LNG exporter this year, the U.S. has replaced Malaysia as the third-largest LNG exporter. By 2025, the U.S. could even become the world’s largest LNG exporter if it manages to increase exports, as some analysts predict, from 17 bcm/y in 2017 to more than 200 bcm/y by 2040.

The biggest constraints on U.S. producers are domestic infrastructure bottlenecks, along with a lack of specialists and other personnel. Rapid depletion of reserves is not a concern for now. Official U.S. gas reserves increased at the end of last November after another giant new shale oil and gas field was found in the Permian Basin. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the new reserves could reach as high as 280 trillion cubic feet of gas, 20 billion barrels of natural gas liquids and 46 billion barrels of oil. The new find accounts for an increase of more than 100 percent in U.S. oil reserves and 65 percent in gas reserves. Further global production growth is expected to come from Qatar, Iran (with the world’s second-largest gas reserves), Canada and Argentina.

Qatar increased its share of the European LNG market to 43 percent in 2018, exporting 14.85 million tons there.

Qatar exported 78 million tons of LNG in 2018 and seeks to remain the world’s largest LNG exporter. Though it sent 73 percent of its LNG exports to Asia, it increased its share of the European LNG market from 39 percent to 43 percent in 2018, exporting 14.85 million tons there. It wants to expand its liquefaction capacity to 110 mtpa by 2026 and has ordered 60 new LNG carriers in South Korea. Qatar is also a major shareholder in the Golden Pass LNG project in the U.S., together with ExxonMobil. The project’s three production trains of about 5.2 million tons per year each will give Qatar much more flexibility to free up LNG volumes from its Ras Laffan plant for the Asian market.

Closer energy cooperation between Qatar Petroleum and ExxonMobil, as well as between the Qatari and U.S. governments, could significantly strengthen both suppliers. They would dominate the global market, together accounting for more than 50 percent of the total LNG trade over the next two decades. The Trump administration has urged Qatar to challenge Russia’s gas dominance in Europe by cooperating with the U.S. on increasing LNG supplies to the continent.

Facts & figures

Global liquefaction capacity and LNG production

This year, final investment decisions for new LNG export projects of at least 82 bcm/y are expected to be made worldwide, but this could even rise to 291 bcm/y (211 mtpa – see below). Such investments will hugely intensify global gas market competition.

Facts & figures

List of planned FIDs in 2019 and their LNG capacities

In the fourth quarter of 2018, due to slowing demand and an unseasonably warm winter in Asia, gas prices there fell below Europe’s for the first time in several years. Asian LNG spot prices have already fallen below those on the UK spot market for the first time. LNG traders began redirecting their cargoes from Asia to Europe, benefiting from well-developed gas hubs and huge underground storage facilities, which Asia lacks.

Scenarios

Stung by growing domestic and foreign criticism of Nord Stream 2, the German coalition government has decided to support the construction of at least two LNG import terminals. But this gesture will not end the debate over Germany’s increasing reliance on Russian gas imports. The new terminals could simply allow the Kremlin to expand (subsidized) Russian LNG exports to Europe from Novatek and Rosneft, ending Gazprom’s monopoly on gas exports to Europe.

As U.S. LNG exports increase over the next decade, they will challenge Russia’s position in the European market. Gas prices in Europe could come under downward pressure as early as this year, though they could tighten again after 2022, until a third wave of new LNG supplies from the U.S. and other exporters arrives around 2024-2025. Prices may slump more if the U.S.-China trade dispute drags on. American LNG exports to China have already significantly declined due to the trade standoff and because China wants to ensure the security of its energy supplies.

In fact, last winter U.S. LNG sales to Europe increased fivefold, according to Reuters, with its exports to Europe exceeding those to South Korea and Mexico. The spike made Europe the largest buyer of U.S. LNG exports for the first time. Still, these developments were mainly driven by market forces, and less by President Trump’s energy policies supporting LNG. Those policies are likely to have a greater impact in the coming years.

Nevertheless, the global shale revolution has just begun. It will have strategic, geopolitical effects on global LNG trade patterns and gas markets, potentially causing much more disruption than many have so far predicted.