Oil in the energy transition age

Concerned that demand for oil will eventually vanish, energy companies are gradually moving away from fossil fuels and toward renewable energy sources. However, this trend does not apply to nationalised companies, which are proving less responsive to external incentives.

In a nutshell

- Oil producers are rebranding themselves as ‘energy companies’

- The shift away from oil will be driven by political factors

- National companies will benefit from the transition

Around the world, governments are introducing aggressive policies to promote the expansion of green energy in the hope of replacing fossil fuels, regarded as the main culprit behind carbon emissions and global warming. The aim is a drastic transformation of the world’s energy system – from its current state of reliance on coal, gas and oil to one where primary energy needs are predominantly, if not solely, met by sources that emit no carbon dioxide (CO2).

Public pressure is mounting to accelerate the energy transition. Demonstrations such as those organized by “extinction rebellion” activists are but one example. The financial community has also started to join the march toward a greener future, redirecting funds from the “dirty” fossil fuel sector to the more noble green cause. International financial institutions are leading the charge. The World Bank, for instance, decided not to fund any investments in upstream oil and gas after 2019. Similarly, the European Investment Bank announced it would phase out fossil fuel financing. Large global asset managers like Blackrock will now assess environmental performance when investing in companies. Even charities and art galleries are turning away funding that comes from “dirty” oil.

Companies in the fossil fuel business ought to be concerned. They are told that the market for their core products will shrink and eventually disappear, and that oil and gas reserves will simply lose their value, irrespective of their size. The very end of the “age of oil,” which has been predicted on so many occasions, may be finally around the corner. The only question seems to be when.

Since oil and gas are too big to disappear instantaneously, the energy transition will have a significant impact on the industry’s structure. Politics, not economics, will drive the transformation – which is likely to benefit national oil companies at the expense of private incumbents.

Facts & figures

Big oil at the crossroads

- Qatar is building an 800-megawatt solar power project that will push the country far beyond its announced goal for solar energy. The Al Kharsaah plant near Doha will generate about eight times the amount of the solar energy Qatar had pledged to build, and will help the country host a carbon-neutral World Cup event

- Equinor powers more than one million European homes with wind energy from four offshore wind farms in the United Kingdom and Germany

- In 2004, BP opened two hydrogen fueling stations designed to facilitate the field-testing of fuel cell vehicles and fueling infrastructure in the U.S. A year later, it opened its first hydrogen demonstration refueling station in the UK

- Fossil fuels still meet 81% of the world’s energy needs (with 60% coming from oil and gas). The remaining 19% comes from renewable and nuclear energy

- Saudi Aramco is the world’s largest oil company

Rebranding or taking the lead?

Haunted by the perception that oil and gas cannot exist in a green future, the industry’s instinctive reaction has been to try to position itself as compatible with, and in favor of, the energy transition. One argument is that oil and gas and coal need to be present for some time to avoid the economic consequences of disrupting the energy supply. Another is that energy companies are centers of expertise that can be entrusted with managing the transition to a low carbon system.

The industry-led Oil and Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI), which launched in 2014 and comprises private and state-owned companies (BP, Chevron, CNPC, Eni, Equinor, ExxonMobil, Occidental Petroleum, Pemex, Petrobras, Repsol, Saudi Aramco, Shell and Total), states that its members “are dedicated to the ambition of the Paris Agreement to progress to net zero emissions in the second half of this century.”

Public pressure is mounting to accelerate the energy transition.

It also adds that “energy companies have an important role to play in accelerating the energy system transition required to tackle the climate challenge urgently, alongside governments, civil society and other key stakeholders, while continuing to provide reliable, accessible and affordable energy for all.” A similar point was made by the International Energy Agency (IEA), which argues that “the resources and skills of the industry can play a central role in helping to tackle emissions from some of the hardest-to-abate sectors.”

The switch to “energy companies” instead of “oil and gas companies” is an attempt to convey a more inclusive image of the industry. Earlier this year, French oil company Total announced that it would build its largest solar power project to date in Qatar, in collaboration with the Japanese investment group Marubeni. The company’s CEO, Patrick Pouyanne, stated that the project is “a very clear symbol of the strategy of Total to become a global energy company.” Back in 2018, Norwegian national oil company, Statoil, changed its name to “Equinor,” dropping the “oil” component: “Our name change supports our strategy as a broad energy company,” the firm said.

Greening energy

A survey of some of the largest oil companies in the world indeed seems to indicate a change of heart. Many of them are expanding their portfolio to include renewable energy. In 2016, Shell established its New Energies business, which focuses on investing in the global deployment of green energy (from hydrogen and electric vehicle charging, to biofuels, renewable power and reforestation). During the same year, Total announced the formation of a new gas, renewables and power division with the aim of raising the share of company-wide low-carbon business to 20 percent in 20 years. Equinor aims to become a global offshore wind producer. The company is already the world’s leading floating offshore wind developer. ExxonMobil is funding research in algae biofuels as part of its investment into emission-reducing technologies, while Eni wants “to lead the energy transition” with decarbonization.

BP was the first oil major to commit significant capital to renewable energy through its “Beyond Petroleum” campaign, which was first launched in 2001. Following a recent change in leadership, an expansion of the company’s climate targets and an acceleration of spending on renewable and low carbon energy are anticipated. BP’s new CEO, Bernard Looney, has pledged to achieve a net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 or sooner – probably the most ambitious green target by the industry to date.

On average, less than one percent of oil companies’ expenditures are made on projects outside their core activity.

And yet, despite all these attempts and the favorable press they are receiving, the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that on average less than one percent of the total capital expenditures of leading oil and gas companies are made on projects outside their core activity of securing continued supplies of oil and gas. The largest outlays are solar and wind energy. This amounts to just over $2 billion since 2015.

At current speed, total expenditure would be around $15 billion by 2035 – a far cry from the $350 billion investment in wind and solar power which would be required for these companies to reach the same market share they have in oil and gas, according to Wood Mackenzie. Clearly, oil companies will have to step up their efforts considerably if they want to contribute to the energy transition as significantly as they claim.

Divergence

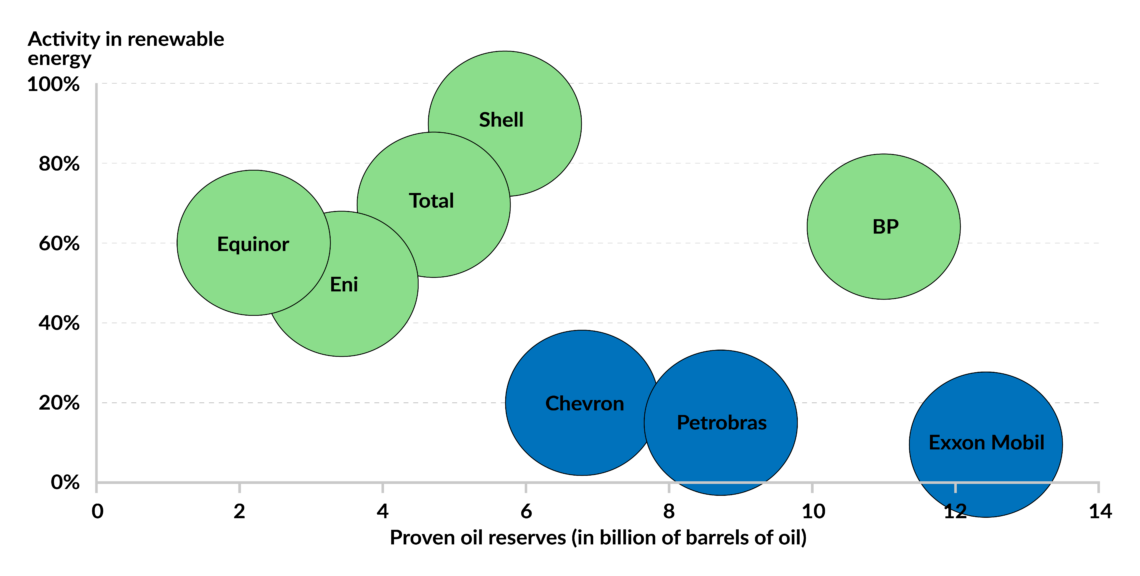

Not all large oil companies are following the same path. An interesting study found a strong link between proven reserves of oil majors and their activities in renewable energy. Those with smaller levels of proven oil reserves are moving into the renewable space faster than those with large pools of oil reserves (with BP being the exception).

This empirical observation squares well with the intuitive explanation that, at a time when investment activities in finding new oil and gas resources are under scrutiny and threat, companies that have less reserves feel more pressure to redirect their portfolio of activities toward green energy.

Facts & figures

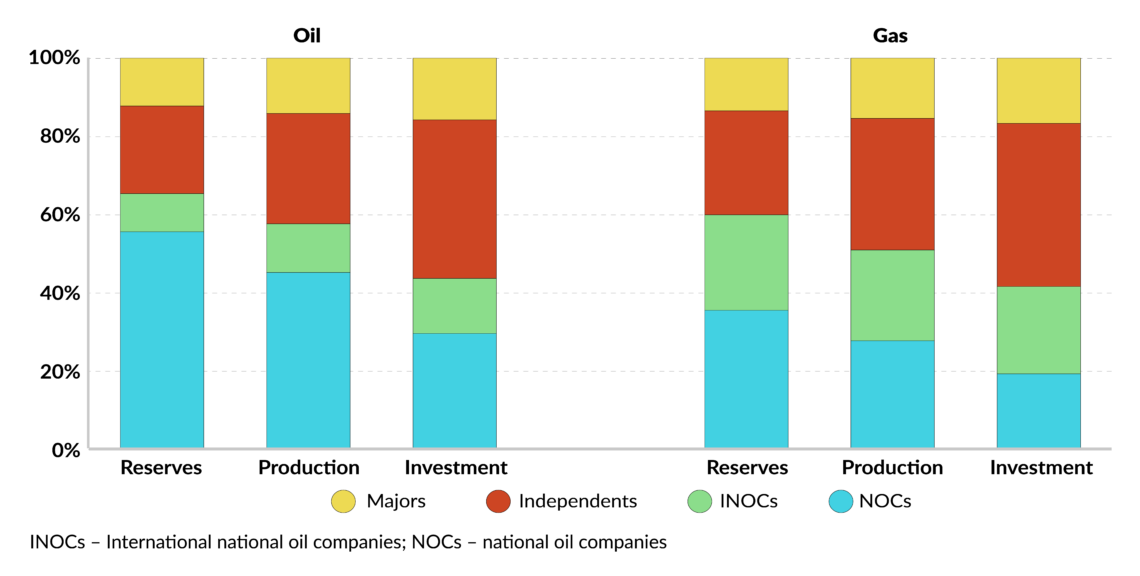

However, it also sits well with another observation: national (state-owned) oil companies (NOCs) appear to hugely lag their private peers when it comes to investing into noncarbon activities. Sitting on the world’s largest proven oil reserves, the world’s biggest NOCs – despite officially acknowledging the need to support the energy transition – are pouring capital into their oil and gas activities throughout the supply chain instead.

Saudi Aramco, for example, the world’s largest company, earmarked $500 billion to invest over the next 10 years in oil and gas and petrochemicals. Meanwhile, it also revealed plans to launch a $500 million fund that will promote energy efficiency and renewable technologies. Other NOCs exhibit similar production profiles – when they publish any information at all. Clearly, such companies are not turning their back on their core business, and no one expects their government owners to impose a significant reduction of the share of oil and gas on their portfolio. After all, their business is the backbone of local economies.

Unintended consequences

The energy transition may therefore have the unintended consequence of changing the structure of the industry producing the remaining oil and gas that will be required during the lifetime of the energy transition.

In countries that are most aggressively adjusting to the requirements of the Paris agreement (most of them in the OECD, which is also home to the large oil majors), companies will be under increasing pressure to expand the share of renewable energy in their portfolio at the expense of oil and gas. As they lose the ability to maintain production, the oil and gas needs of the world will increasingly be covered by national companies. Until recently, a development like this would have been considered a global security risk. This time around, however, with consumer nations focused on reducing carbon emissions, it is slipping by almost unrecognized.

The more successful the energy transition, the more it threatens to benefit those NOCs that stick to the conventional model – at least during the next few decades of the transition, when oil demand will continue to exist. Unfortunately, the history of the global oil and gas industry is full of examples showing the risks of political interference.

Analysts now forecast peak demand somewhere around 2035.

Sooner or later, even the remaining producer companies will be pitched against each other, engaged in fierce competition over a rapidly shrinking share of oil and gas supplies for the world. Many of them (and thus the countries that depend on them) will be ill-prepared – and the demand for oil and gas may fall much faster than predictions suggest.

During the first decade of the century, oil market commentators focused on “peak oil” supply – the idea that the world was running out of oil, or at the very least, out of cheap oil. Technological advances have since allowed the oil industry to tap into previously nonviable sources of oil, such as shale oil, and this has put this idea firmly to rest. Instead, the focus of observers has since shifted to “peak oil demand” – the theory that the world is approaching an inflection point after which global oil demand will start to decline, independently of the energy transition.

Peak demand would be caused by a steady increase in the efficiency with which oil is used, combined with technology that makes oil unnecessary in many applications. Both will speed up the transition to a world that is less oil dependent. Oil demand has been growing for more than 150 years. Many analysts now forecast peak demand somewhere around 2035, when the oil market will plateau and start to decline.

To the extent that the energy transition does bring about this phenomenon, it will trigger fierce competition for the right to sell the remaining resources, which will in turn lower prices, and may catch by surprise those who thought they had more time to adapt. Big losses for companies (including NOCs) that have invested billions of dollars in long-term oil and gas projects and social upheaval could result.