Oil markets: What crisis?

Crude oil prices are again hovering above $80 per barrel, but oil markets are not in crisis mode. The main force pushing up the prices of oil has been OPEC’s tightening of available supplies. Absent robust economic growth, the policy will not sustain high oil prices for long.

In a nutshell

- Oil prices have returned to pre-Covid heights

- The gas crunch barely affects the oil and coal markets

- To stay high, oil prices need to be driven by strong energy demand caused by sustained economic expansion

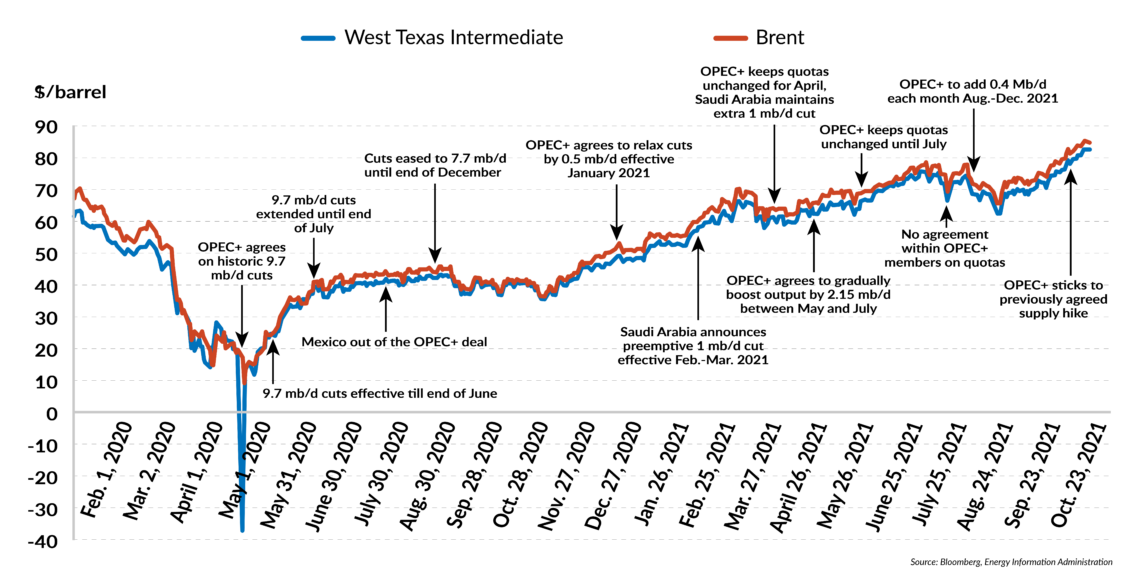

After a brief sluggish period in August 2021, when oil prices reversed the gains made in June and July, by the fall prices regained momentum. In October, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crossed $83 per barrel (bbl) and Brent exceeded $85/bbl – for the first time since the pre-Covid heights of October 2014 and 2018, respectively. Perhaps even more tellingly, prices have more than doubled since October 2020. Historically, this is an impressive recovery by any standard – but especially so when considering the unprecedented scale of the pandemic-induced crisis.

The upward march in oil prices has coincided with skyrocketing gas (and coal) prices, prompting fears of a full-blown energy crisis. In reality, despite the optics, oil markets are not in crisis mode, at least not for now. To put things into perspective: oil prices have increased by 38 percent since January 2021. The Title Transfer Facility natural gas prices in Europe (TTF is a virtual trading point for natural gas in the Netherlands) increased by 400 percent over the same period.

The driving force that helped bring oil prices to their current levels has been the mammoth effort of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and its allies (commonly known as OPEC+) to curtail the availability of existing supplies. It is this political decision that is sending the price signal we are all receiving today. However, in the longer term, it will be economic growth that decides how tight the market will truly become.

Facts & figures

Daily spot oil price, Jan. 2020-Oct. 2021

Tight market

Based on the rapid recovery in oil prices alone, the only legitimate conclusion is that the market is tightening rapidly – which is currently the prevalent view. In general, for a market to tighten, demand must increase faster than supply, causing a rapid drawdown in inventories, which exercises upward pressure on prices.

There is no doubt that market fundamentals are lending support to an increase in prices. On the supply side, not much has happened to offset OPEC+ supply cuts. Negotiations with Iran, for instance, have not gone too far. At the same time, Hurricane Ida hit the United States in August, disrupting oil production in the Gulf of Mexico. By October, around 16 percent (nearly 300,000 barrels per day) of the province’s output was still offline, according to the regulator Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE).

For each of the above factors supporting higher oil prices, there is a caveat.

On the demand side, the vaccination rollout, particularly in the world’s largest economies, continues to improve the macroeconomic environment, boosting oil demand. Meanwhile, the gas crunch is having some spillovers into oil markets as customers look for a cheaper substitute. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that the gas crisis could add about 500,000 barrels a day to oil use on average over the coming six months.

As a result of these dynamics, stock draws have continued. According to the IEA, in September, OECD industry stocks fell by 23 million barrels (MMbbl) and stood at 210 MMbbl below their five-year average and were lowest since March 2015.

Caveats

The problem, however, is that for each of the above factors supporting higher oil prices,there is a caveat.

Take the macroeconomic outlook, for example. In its World Economic Outlook published in October, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) states that “global recovery continues, but the momentum has weakened, and uncertainty has increased.” The IMF downgraded its economic growth forecasts for major economies in its October publication compared to July. The U.S., the world’s largest economy and oil consumer, saw its gross domestic product (GDP) growth figures revised downward from 7 percent to 6 percent.

China, the first country to be hit by the coronavirus and the first to overcome it, is also seeing its recovery decelerating. Although its economy grew by 4.9 percent in the third quarter this year compared with the same period in 2020, it hardly expanded compared to the second quarter this year (only 0.2 percent), one of the country’s weakest performances in more than a decade. China is the world’s second-largest economy and oil consumer after the U.S.

The market is driven by a producers’ group which is allowed to restrict production.

As for the additional oil demand resulting from the crisis in gas markets, this is far from being a done deal because of the uncertain path the crisis might take. Hard-to-predict factors such as the weather could play an important role and the substitution between oil and gas is not consistent across countries and regions.

On the supply side, disruptions due to the hurricane are temporary, while non-OPEC+ supplies, particularly U.S. shale, are creeping back in. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) expects world supply growth to outpace growth in oil consumption in 2022, which will exercise downward pressure on prices. According to the EIA, they would average $72/bbl (Brent).

Regarding the inventories, the main caveat is that data for non-OECD stocks is not publicly available. As a result, any estimates are based on educated guesses.

Where next?

Of course, the fundamental economic dynamics are currently pointing to a market that is becoming “tighter” over time. However, this is only part of the story. Today, the market is driven by a producers’ group which is able (and allowed) to restrict production. Therefore, prices are determined by the group’s political decision, setting them higher than they would otherwise be. Had it not been for OPEC+’s historic production cuts, prices wouldn’t have been where they are today. In all fairness, the decision to let OPEC+ do the cutting, as opposed to relying on the market, was supported broadly during the April 2020 meeting, particularly by the U.S., with former President Donald Trump boasting about his role in brokering the deal.

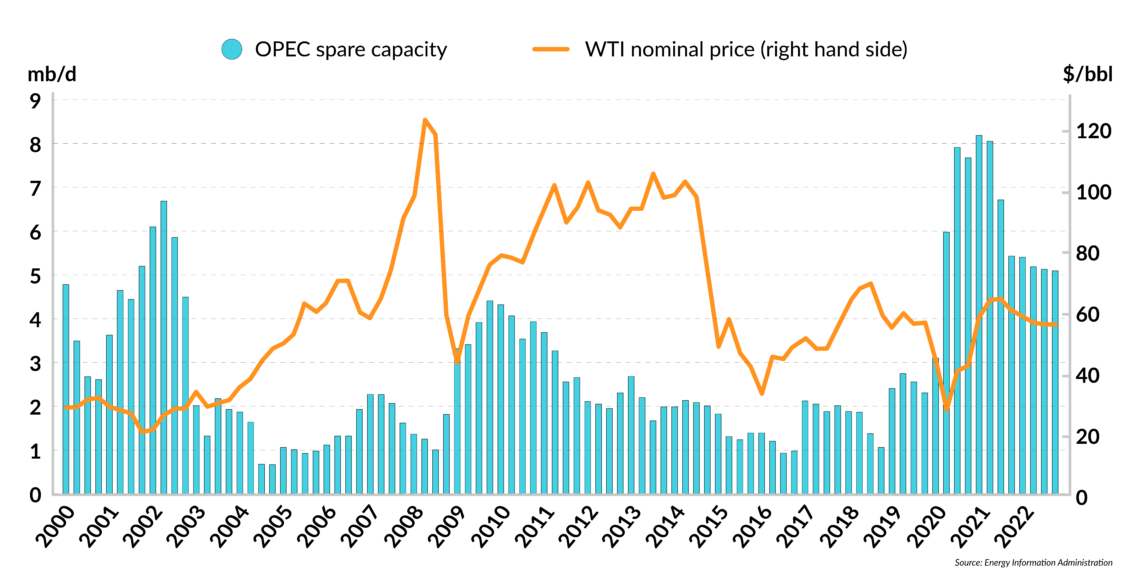

For a more comprehensive understanding of where markets are heading next, one needs to bring in a topic that is not discussed as often as the commercial inventories in consuming nations: OPEC spare capacity.

The EIA defines spare capacity as the volume of production that can be brought on within 30 days and sustained for at least 90 days. High prices are typically observed when oil demand rises fast, and OPEC spare capacity is running low. The only exception in the last 20 years was in 2014 when both prices and spare capacity were low. At that point, OPEC was engaged in its first “price war” with shale oil. The cartel had decided to open all taps and pumped at full capacity to eliminate the newly emerging competition from shale oil – only to give up on this attempt after 2016.

Facts & figures

OPEC spare capacity and oil prices

From these past trends, one important observation emerges. What we have today is a combination of rising demand and high OPEC spare capacity. At first sight, this is just like the early 2000s, when demand was rising fast, driving down OPEC spare capacity and causing it to shrink until it had evaporated to less than 1 percent of global supply. Are we likely to see a similar quick erosion and further price increase again?

Today’s oil markets have a significant safety cushion in the form of OPEC spare capacity.

The answer will not be given by energy markets. It will depend on the economic recovery. Back in the early 2000s, the relentless increase in demand was driven by the growth and industrialization of China and other emerging markets. It was not a “rebound,” as the U.S. Fed describes the current state of affairs, but a genuine, solid economic trend growth which continued until the global economic crisis in 2008/09 put a (small, as it turned out) wave breaker in its way. Other than using up OPEC’s spare capacity, the global oil market, had no way of providing timely supply increases for that robust economic growth. So, prices began to rise relentlessly until the crisis. In the end, the supply response of the system included shale oil, reacting to the high prices at the time.

Today, we are indeed facing a strong recovery in demand. But the longer-term price development will depend on whether we face another period of extended, strong economic growth, causing oil demand to keep on rising beyond the levels it had reached before the pandemic in early 2020 – or whether stimulus measures and pent-up demand after the pandemic will just ignite a short flash of “catch-up” growth. We might see the global economy returning to its old slow growth path – or even less than that – after reaching pre-pandemic levels. With the way things are currently going, the latter scenario is more likely.

Facts & figures

Energy projections

- The EIA estimates Brent prices will average $81/bbl during the fourth quarter of 2021 - $10 higher than their previous forecast

- Goldman Sachs lifted their year-end forecast on Brent crude oil to $90/bbl from a previous forecast of $80

- OPEC expects global oil demand to exceed its pre-pandemic levels in 2022

- According to the IEA 2021 World Energy Outlook, the amount being spent on oil and natural gas is geared toward a world of stagnant or even falling demand for these fuels

- Oil output in the shale Permian Basin in the U.S. is nearing pre-pandemic record levels

- In July 2021, OPEC+ agreed to extend their current deal from April 2022 to December 2022

- In low-income countries, the majority of which are in Africa, around 2 percent of people have received a single dose of the COVID-19 vaccination

Back in the first decade of the millennium, the market was genuinely tight as global supply struggled to meet the growth in demand. Back then, discussions about peak oil supply (that the world was running out of oil) and security of oil supplies dominated energy debates.

This is surely not the case today. Although it may come across as a strange thing to say during a widely perceived “energy crisis,” today’s oil markets have a safety cushion in the form of OPEC spare capacity. The way OPEC and its allies choose to play that card will surely influence where prices go. However, it will once again be economic growth that determines how tight the market will become in the longer term.