OECD rules risk fueling competition for state subsidies

The push for harmonized global corporate taxes will bring a bad side effect: a spending race among governments to attract foreign direct investment.

In a nutshell

- New global tax rules alter the game for attracting foreign investment

- State subsidies replace business-friendly tax rates as the driver

- While competition on taxation brought growth, subsidies distort markets

For decades, the European Commission and international groups like the World Trade Organization and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have stood against state subsidies for domestic industries. They correctly emphasized that subsidies are economically distortive, undermine fair competition, favor politically connected businesses or sectors over others and slow economic growth. Policymakers have not always succeeded at limiting state aid, but the harms of such favoritism were frequently recognized.

New OECD global minimum tax rules risk shifting competition for international business investments from economically beneficial tax-rate competition to economically costly government subsidies. New policies advanced by the European Union and the United States further undermine the consensus against subsidies and risk igniting a state-aid race.

Citizens and businesses should be aware of this policy shift. As individual countries turn to subsidy-driven industrial policy, the OECD’s new global minimum tax risks institutionalizing this new system of state fiscal support for private industry.

The OECD agenda

The product of decades of OECD initiatives to rewrite the taxation of international corporate profits, nearly 140 countries’ executive branches recently agreed to a Global Anti-Base Erosion (GloBE) proposal. The proposal is a two-pillar approach to overhaul the global taxation system. The first pillar includes a revolutionary new tax so that some countries can tax corporate profits without the historical safeguards that require a firm’s physical presence in the taxing country.

Tax-rate competition incentivizes investment decisions based on genuine economic potential, fostering an environment where business operations are driven by market fundamentals rather than selective state intervention.

The second pillar, and the focus of this report, is equally transformative. It introduces a global minimum corporate tax designed to put a floor on acceptable tax rates, preventing countries from choosing a corporate tax rate below 15 percent. The minimum tax is enforced by an extraterritorial mechanism that allows high-tax countries to tax multinational income earned in other jurisdictions.

In this new capacity as a global tax regulator, the OECD has designed the minimum tax in a way to incentivize countries to compete for international business investment with state subsidies, undermining free and fair international markets.

Competition for capital: Tax rates or subsidies?

Countries compete for global business on innumerable margins. Firms make location decisions based on natural resources, workforce characteristics, rule of law protections and regulatory environment. Many countries also compete for global businesses using fiscal policy: direct expenditures, tax incentives and rates.

Tax competition based on tax rates is more transparent, fair and economically efficient than competition through state subsidies, such as tax credits or direct expenditures. Tax-rate competition incentivizes investment decisions based on genuine economic potential, fostering an environment where business operations are driven by market fundamentals rather than selective state intervention.

Facts & figures

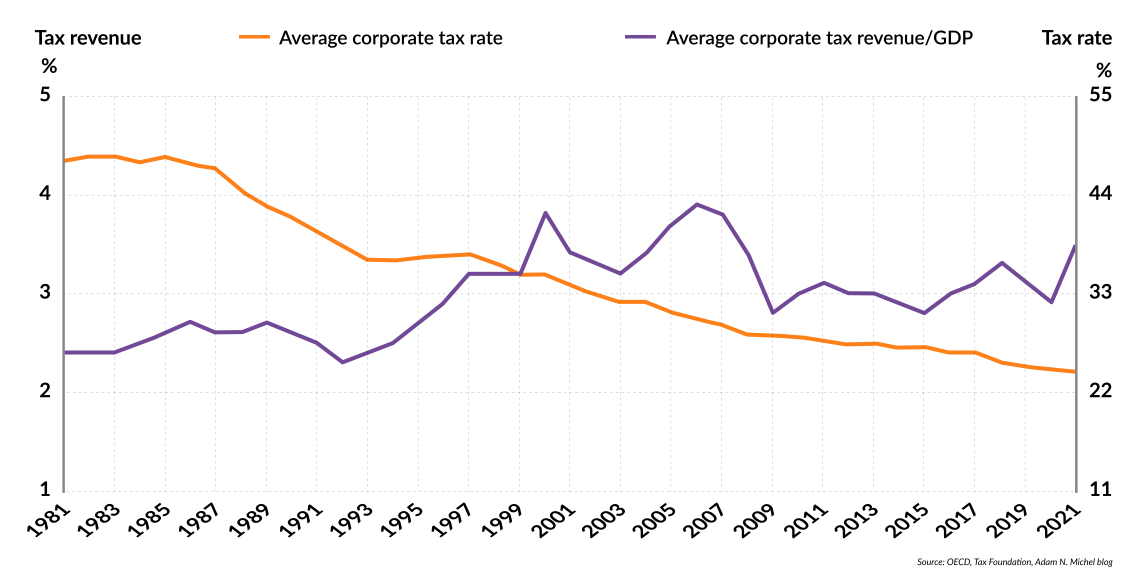

Average OECD corporate tax rates and revenue, 1981-2021

This type of tax rate competition has helped drive average statutory international tax rates down from almost 50 percent in the 1980s to about 24 percent today, a shift that has helped foster significant increases in global investment and economic growth.

In contrast, state subsidies lead to market distortions, as they typically favor specific industries, regions and individual businesses. Targeted subsidies create an opaque economic landscape where success hinges on preferential political treatment rather than competitive merit and market innovation. The political process by which allowances are allocated also breeds corruption, as firms vie for special treatment.

There were early signs that the OECD GLoBE rules would target all types of fiscal policy competition, defining not just a minimum tax rate but also a tax base that excluded all forms of state support, targeted tax subsidies and direct subsidies. The most recent OECD guidance now makes clear that the Pillar Two minimum tax rules target primarily competition on tax rates, with the effect of pushing international fiscal policy competition to the more inefficient form of targeted subsidies.

The OECD’s GLoBE rules will not reduce governments’ incentive to attract new businesses to their countries; they will shift the margins on which this competition takes place.

It does this by treating refundable tax credits (cash payments through the tax code) and direct state subsidies as income instead of reductions in taxes paid. For example, this means that instead of lowering the corporate tax rate for all firms from 16 percent to 11 percent (and facing OECD penalties for falling below 15 percent), countries can make equivalent direct payments to domestic industries. For a firm making a $100 profit, a 5 percentage-point tax cut would save them $5 but subject them to the new OECD clawback rules under the minimum tax.

However, if that $5 is paid to the firm as a direct state subsidy, its effective tax rate remains just above the OECD-approved 15 percent.

The minimum tax structure is particularly challenging for the U.S. and other similarly situated countries that provide comparatively few direct cash or cash-equivalent subsidies to private businesses. When the U.S. Congress subsidizes companies, it has historically done so with non-refundable tax credits, reduced tax rates and deductions. For example, the U.S. research and development (R&D) tax credit subsidizes targeted activity by reducing federal corporate income tax payments, but it is not a direct payment to U.S. firms without any tax liability. Under the new OECD rules, non-refundable tax incentives and topline tax-rate cuts reduce the OECD minimum tax-rate calculation about five times as much as a direct state subsidy or fully refundable credit.

The coming subsidy wars

The OECD’s GLoBE rules will not reduce governments’ incentive to attract new businesses to their countries; they will shift the margins on which this competition takes place.

Some countries have already begun reforming their fiscal systems in response to the OECD’s proposal. For example, Reuters reported that Vietnam is considering ways to directly compensate Samsung and other foreign companies for the higher taxes the firms will be forced to pay under the new 15 percent minimum rate.

For many low- or no-tax jurisdictions, the incentives of the OECD system may push them to impose the new 15 percent top-up tax on domestic firms. If they do not, other countries can tax the so-called “under-taxed profits” earned in low-tax jurisdictions. For countries that have competed on tax rates (such as tax havens), it is a lose-lose. Either they add the new minimum tax, or someone else will. Responding to these incentives, previously no-tax Bermuda will introduce a 15 percent corporate income tax in 2025.

If the U.S. follows through on its retaliatory threats against countries imposing extraterritorial minimum taxes on American businesses, the worst parts of the OECD plan may stall.

Many smaller countries will face tough choices in maintaining their economic model of attracting foreign investment. One attractive option will be to return the new top-up tax government revenue to businesses through direct subsidies. Instead of indiscriminately attracting all companies that could benefit from a country’s attractive tax environment with one low tax rate, governments must determine which companies to lure in with specific subsidies.

These countries will be forced to shift to a less efficient and more corruption-prone system of governmental favoritism. In other contexts, we have seen this type of subsidy war. Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands compete with direct financial support to attract rum distillers as the territories vie for a share of U.S. rum-tax revenues. When they cannot compete on tax rates, governments turn to subsidies.

Scenarios

More likely: Competition on the wrong margin

The OECD may unleash a complicated and very costly economic process in its crusade to end tax-rate competition. The OECD’s GLoBE rules could turbocharge other policy developments in the EU and the U.S. The EU’s new STEP initiative and Temporary Crisis Framework shift the bloc’s economic policy toward fiscal subsidy regimes. The U.S. recently has created a more than $2 trillion fund in mostly open-ended OECD-compliant tax subsidies for politically popular domestic energy technologies and other industries.

The OECD Pillar Two rules will not eliminate competition among governments. These rules will instead entrench the recent shift to subsidy-driven industrial policy and move some competition from the economically more neutral rivalry over tax rates to contest for more economically inefficient direct payments to private businesses.

Less likely: Continued uncertainty

The OECD minimum tax proposal is often presented as a fait accompli – an EU-U.S. brokered deal whose only uncertainty is when it will be agreed to, not if it will be implemented. However, there is growing opposition to parts of the agreement – particularly the under-taxed profit rule – especially among Republicans in the U.S. Congress. If the U.S. follows through on its retaliatory threats against countries imposing extraterritorial minimum taxes on American businesses, the worst parts of the OECD plan may stall. Governments could choose to implement only the domestic components.

In this scenario, competition on tax rates will remain alongside existing initiatives that focus on fiscal subsidies. The perceived failure of the OECD process will likely result in additional attempts at new projects through the OECD or the United Nations. Stalling the OECD Pillar Two minimum tax would allow tax rates to remain competitive for several years longer. Eventually, however, political forces will agitate again to centralize corporate taxation. One can only hope they will continue to fail to launch.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.