Striking a delicate balance

After a period of stagnation, oil markets have begun to recover. This development is mostly due to production cuts by the OPEC+ group. However, oil demand is not expected to reach pre-Covid levels in 2021 – and the transport sector may struggle to return to the status quo ante.

In a nutshell

- Oil prices have started to rise again

- OPEC+ is maintaining impressive cuts

- Steep challenges await in 2021

Oil prices have ended the year on a relative high, compared to levels since March. Prices are still lower than at the beginning of the year. But they have picked up after six months of inertia and seem to be heading in the right direction from the point of view of major oil producers like OPEC+, which is taking credit for the uptick.

Several questions remain. First, it is unclear whether oil prices can maintain their momentum into the immediate future and throughout 2021. Many factors are hazy, particularly on the demand side. A second set of issues, this time on the supply side, revolve around the prices that OPEC+ will deem satisfactory. The organization may aim for price levels that would get the major producing countries closer to balancing their budgets. But this will also depend on the price growth needed to revive production outside the group, particularly with shale oil in the United States.

Facts & figures

Recent developments

- In its December economic outlook, the OECD projects a -4.2% global GDP growth for 2020 and 4.2% for 2021

- The head of Global Pharma Group predicts there will be 10 Covid vaccines by the summer of 2021

- As of December, commercial flights are just above 53% the levels reached in 2019

- Even at a production level of 11 mb/d, the U.S. remains the largest oil producer in the world

- Thanks to shale oil production, the U.S. has doubled its market share in less than 10 years

- OPEC+ has been active for 4 years now - it was established in December 2016

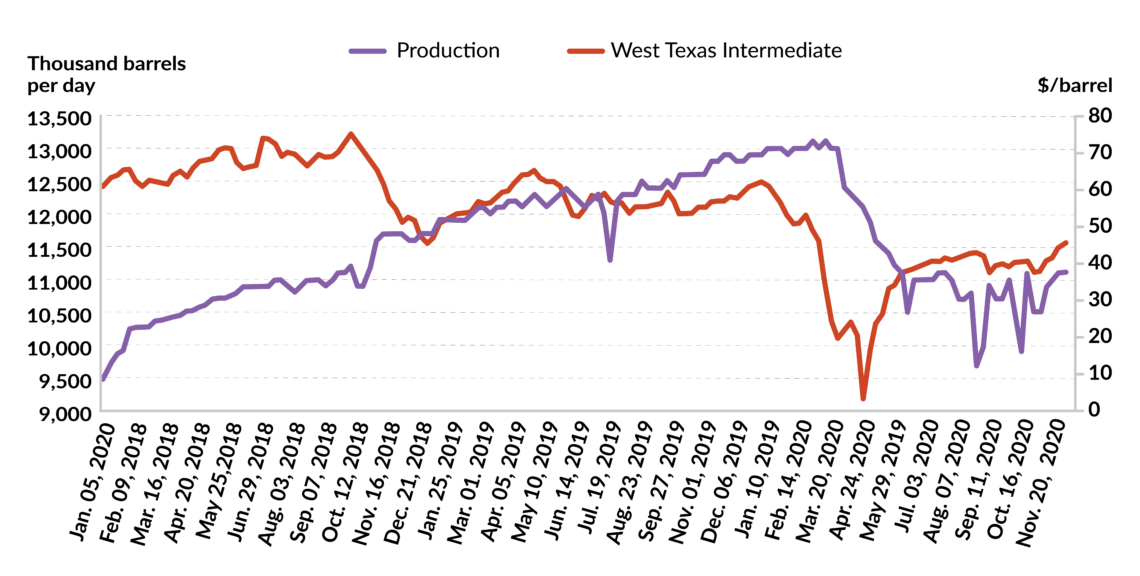

Most commentators agree that U.S. shale oil has had its heyday and will never return to this year’s peak of nearly 13 million barrels a day (13 mb/d). There is no doubt that the U.S. shale industry is deeply bruised – but so is the global oil industry, whether state or privately owned.

Should shale output defy expectations, as it has done on several occasions in the past, OPEC+ would face, once again, tougher competition – offsetting the benefits of higher revenues brought on by market recovery.

Pushing higher

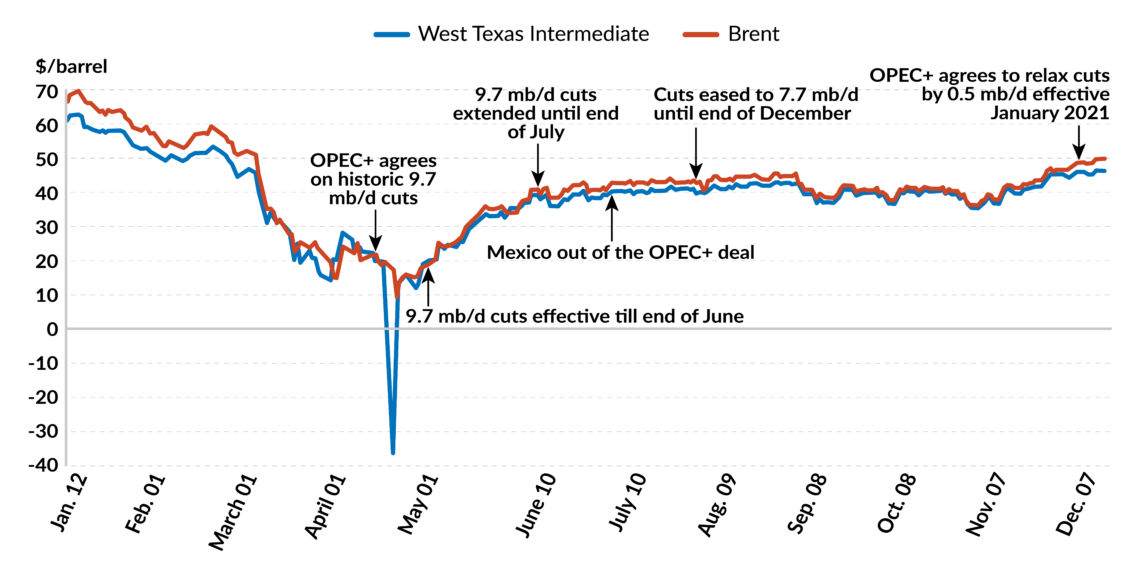

In December, oil prices broke out of the range – $40-45 per barrel for Brent crude – where they had lingered since June of this year. Brent has since been trading nearer to $50 per barrel, indicating that the recovery that had stalled after May might be regaining steam.

While oil producers are relieved, one cannot help but wonder if this momentum is sustainable, and how much the price of oil will rise.

Prices kept rising amid the general optimism triggered by recent developments.

News on the availability of Covid-19 vaccines has surely boosted confidence in next year’s economic and energy outlook. Most of the credit behind the rise in prices goes to the extraordinary effort of OPEC+, which continues to withhold 7.7 mb/d from the market – the largest cut in history. In December, the group met to decide whether to relax its cuts by 2 mb/d as of January 2021. This was the plan set out in the original April 2020 agreement, and the course of action favored by countries such as Russia and Kazakhstan. Meanwhile, other countries like Saudi Arabia would prefer to delay the decision by a few months. After heated negotiations, it was agreed to relax production cuts by 0.5 mb/d as of January 2021. The decision will be reviewed on a monthly basis, “with further monthly adjustments being no more than 0.5 mb/d.”

Prices, which had started to go up ahead of the meeting, kept rising amid the general optimism triggered by recent developments. OPEC+ appeared stable and in control, production increases were smaller than originally envisaged, and there was newfound hope thanks to vaccines. Moreover, gradual inventory withdrawals and the promise of a stable monitoring mechanism for the future contributed to this buoyancy.

Despite the overall boost in market sentiment, however, OPEC+ recognizes that the crisis is not over, with the oil demand outlook particularly uncertain. The change in tactic, namely the monthly strategy review, highlights the instability of the situation. However, given the divisions between the organization’s members, revisiting a decision every month as of February could trigger the very conflicts that the tactic was designed to avoid.

Facts & figures

Demand outlook

According to the International Energy Agency, oil demand has recovered from the bottom low recorded in the second quarter of this year, and it will maintain a substantial recovery rate. However, it will continue to fall below pre-Covid levels by around 6 mb/d and will not catch up before 2022 at the earliest.

Oil demand depends on the speed of economic recovery, which is tied to governments’ fiscal programs and the spending decisions of consumers and businesses. But much will also hinge on the sectoral composition of the uptake, including the strength of the rebound in the transport sector – in particular air travel, hit hardest by the pandemic.

Producers focusing only on pushing prices higher may risk weakening an already fragile demand recovery.

Although mobility has improved in recent months, the latest surveys indicate that transport is unlikely to reach pre-Covid levels for some time. A study by McKinsey, for instance, shows that after the 2008-2009 recession it took nearly two years for international leisure travel to fully recover. International business travel did not fully recover for five years. The coronavirus crisis is much worse than the 2008 financial crisis. Additionally, there may even be permanent changes in behavior following the adoption of remote work during lockdowns. Some of the demand that was lost will never return.

In the longer term, producers focusing only on pushing prices higher may face the risk of weakening an already fragile demand recovery. But there is another reason why high prices may not be that desirable.

Private supply

Many are predicting the imminent demise of shale oil. These forecasts are mostly based on the sheer scale of bankruptcy filings among producers in the U.S. To a seasoned observer, these discussions echo past warnings about peak oil supply, which dominated energy debates in the first decade of the century only to be proven wrong shortly thereafter – largely thanks to the U.S. shale revolution.

The decline in American shale production in reaction to the price collapse this year was expected, since shale is more sensitive to price changes than conventional oil. However, with the increase in prices and subsequent stability since May, shale oil production has also shown signs of recovery.

The question becomes whether U.S. shale oil production will reach levels high enough to take market share from OPEC+, as was the case before Covid-19. The answer will depend on the strength of oil demand, which will affect prices, and on the ability of shale producers to improve their productivity and efficiency. It does not depend on the availability of shale resources, of which there are plenty. One should not underestimate the creativity of the private sector in a competitive market environment (as is the norm in the U.S.). The basic incentives provided by competition move the technological frontiers of any industry.

Waves of financial restructuring in new industries have resulted in better, not weaker, performance.

As for bankruptcies, here too the U.S. has a system in place, which is superior to many other countries, in that it allows for a swift reallocation of resources when companies go out of business. It is not sufficient to simply quote bankruptcies and deduce that the sector must be dead. U.S. bankruptcy procedures allow for the fast transfer of assets from insolvent (and often inefficient) producers into the hands of new investors and owners, typically with more capital. Historically, waves of financial restructuring in new industries – and the shale industry has been no exception – have resulted in better, not weaker, performance than before. Shale is a technology and a resource base, and financial restructuring does not destroy technologies or resources. Low prices do. If prices continue to rise they are likely to contribute to a more productive industry.

Some commentators have gone further by claiming that shale has never made any money and that it must now face its day of reckoning. This claim does not hold up to scrutiny. Almost every new industry is dominated by debt, simply because it is financed this way. Surely the impressive ramp-up in U.S. shale oil production in such a short period of time (from nothing to nearly 8 mb/d in 10 years) indicates that someone has made money and saw the potential for making more. The current restructuring will eliminate some of this debt, a typical consolidation process for “new” and rapidly expanding industries.

Outlook

Going forward, what will matter is the cost of producing oil. While “average” breakeven oil price figures are often quoted, they mask important differences between regions and operators. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, at $40 per barrel, most shale producers have their operating costs covered. The bank’s latest survey shows that an oil price of around $50 per barrel will significantly boost drilling activity.

The recent increase in oil prices, though a blessing at first sight, harbors its own challenges for OPEC+. The group faces a long road ahead, and will need to strike a delicate balance.