OPEC’s next phase

OPEC has regained influence on the back of its cooperation with Russia. Some suggest this partnership could be made formal, while others say doing so would make the organization even more unwieldy. As OPEC tries to achieve “fair” prices, it faces challenges: legislation in the U.S. that allows officials to sue the organization for price-fixing.

In a nutshell

- OPEC has historically had difficulty maintaining “fair” and stable oil prices

- Its partnership with Russia helped raise oil prices and regain the group’s sway

- Market volatility and U.S. legal challenges will present big hurdles

Since its formation in 1960, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) has attracted international interest. Its classification, influence and outlook have divided analysts. The last few years have been particularly interesting. Following the oil price collapse in 2014, some commentators wrote OPEC’s obituary. They announced that time was up for the group, which had “practically stopped existing as a united organization,” to use the words of Igor Sechin, CEO of Russian state-owned oil giant Rosneft.

When OPEC managed to reach a deal in December 2016 with non-OPEC producers led by Russia to form the so-called OPEC+, it regained much of its political and economic clout. After the organization’s June 2018 meeting, some analysts even predicted the birth of a new OPEC – a “Super OPEC.” Meanwhile, in the United States, Senator Chuck Grassley introduced a bill dubbed “No Oil Producing and Exporting Cartels,” or NOPEC, which, if passed, would allow the U.S. attorney general to sue OPEC for price manipulation under the Sherman Antitrust Act. In response, some commentators warned that oil market volatility would increase without OPEC. They may be right, but only in the short term.

This contrast in perspectives has accompanied OPEC throughout its history and it is unlikely to be resolved any time soon. The outlook for the organization largely depends on the future of oil markets, and especially on when oil falls out of fashion. But as gloomy as the latter scenario might appear for the organization, it could make OPEC very effective in defending oil prices.

Raison d’etre

OPEC’s formally stated objective is “to co-ordinate and unify petroleum policies among Member Countries, in order to secure fair and stable prices for petroleum producers; an efficient, economic and regular supply of petroleum to consuming nations; and a fair return on capital to those investing in the industry.” This, however, was not the reason the organization was formed.

OPEC countries realized the strategic importance of oil and wanted to exercise greater sovereignty over its production.

OPEC emerged in an era of increasing nationalism and shifting power from a group of powerful western oil companies dominating the global oil market (the so-called Seven Sisters – see box), to host governments, which had, by and large, nationalized the oil resources on their territories. They had come to realize the strategic importance of oil to modern economies and wanted to exercise greater sovereignty over its exploration, production and distribution, while obtaining a “fair” price for its sale. This aim is clear in the organization’s “Declaratory Statement of Petroleum Policy in Member Countries,” adopted in 1968, which emphasized “the inalienable right of all countries to exercise permanent sovereignty over their natural resources in the interest of their national development.”

Facts & figures

OPEC and OPEC+

- OPEC was founded in 1960 by Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. They were later joined by Qatar (1961); Indonesia (1962, suspended its membership in 2009, then rejoined in 2016 but suspended its membership again a few months later); Libya (1962); the United Arab Emirates (1967); Algeria (1969); Nigeria (1971); Ecuador (1973, suspended its membership in 1992 but rejoined in 2007); Gabon (1975, terminated its membership in 1995 but rejoined in 2016); Angola (2007); Equatorial Guinea (2017), and the Republic of the Congo (2018)

- From around 1920 to 1970, a dominant group of companies emerged and established control over the world oil market. These firms included France’s Total, as well as a group known as the “Seven Sisters”: Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (now BP); Gulf Oil (acquired by Chevron); Royal Dutch Shell; Standard Oil Company of California (Chevron); Standard Oil of New Jersey (Exxon, now part of ExxonMobil); Standard Oil Company of New York (Mobil, also now part of ExxonMobil); and Texaco (merged into Chevron)

- OPEC+: On November 30, 2016, OPEC announced a coordinated production cut of approximately 1.2 million barrels per day (mb/d), limiting its production to around 32 mb/d. A week later, 10 non-OPEC members, led by Russia, also committed to reducing their combined output by an additional 600,000 barrels per day, bringing the total cuts to 1.8 mb/d, effective as of January 2017

- For a conventional oil project, it takes seven to 10 years to convert investment into production. This explains why experts describe the conventional oil supply as “inelastic”: it is not responsive to price changes in the short term. Tight oil is different; the lead time from investment to production has shrunk to months and output is more visibly responsive to short-term changes in prices

What is fair?

As governments asserted greater control over their valuable resource, achieving a “fair” and “stable” oil price has become the organization’s overarching objective. Finding a fair price, however, is rarely simple. In fact, there is no such thing. It is not just that producers and consumers usually disagree on what is fair, oil producers themselves rarely agree about it for long. Oil market dynamics ensure that views of what constitutes a “fair” price constantly change.

OPEC itself includes very different countries: from wealthy Arab Gulf states to much poorer nations in Africa and Latin America. It also includes members with different circumstances, needs and political aspirations. Some even fighting proxy wars against each other, as is the case of Saudi Arabia and Iran. Yet they manage to meet around a table in Vienna and agree on oil policy.

From a historical perspective, OPEC is probably more famous for its discord than adherence to discipline. It is therefore impressive that the organization has managed to overcome these differences throughout the decades, irrespective of its effectiveness.

Stability

The other important dimension of OPEC’s mission is achieving oil price stability. Experience shows that this aspiration has rarely been achieved.

Volatility in oil prices has been an inherent feature of the industry since its early days. As Ida Tarbell reports in her famous book The History of The Standard Oil Company, published in 1904, “From the [beginning of the industry], oil men had to contend with wild fluctuations in the price of oil. In 1859, it was $20 a barrel, and in 1861 it averaged 52 cents. Two years later, it averaged $8.15, and in 1867 but $2.40.”

Today, the oil market is global, with thousands of players involved. In such a huge market, where giant projects react slowly to prices (the exception being unconventional tight oil) price volatility must be expected.

Facts & figures

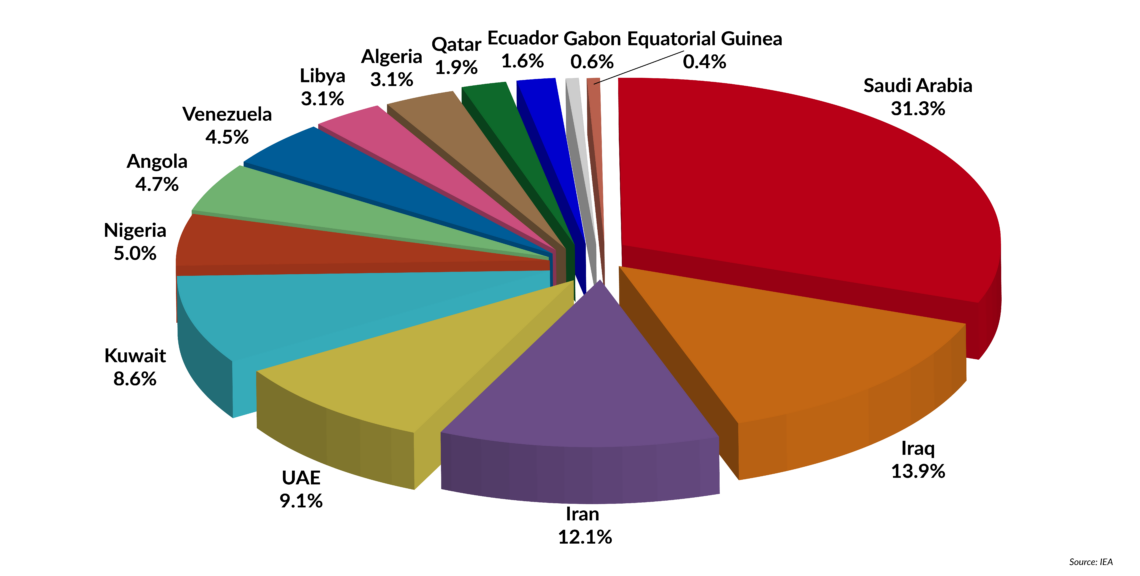

OPEC members' share of the organization's crude oil production (2018)

In all markets, prices are supposed to be flexible to allow an efficient allocation of scarce resources. In oil markets, however, this seems to be harder because oil is either directly or indirectly involved in the production of almost every commodity. It is true that the presence of OPEC, which supplies more than 42 percent of world oil, is likely to dampen short-term volatility. But if prices are not allowed to fluctuate, markets do not work, resulting in even more radical price movements in the longer term.

Companies have learned to live with oil price volatility; it is one of several risks that shape the nature of the oil business. In some cases, government policies have been more volatile than prices, creating a far more challenging environment and making risk much harder to predict.

In many countries, consumers have been artificially shielded from price volatility, either through subsidies or taxes, both of which distort markets. The U.S. belongs to a very small group of countries where consumers are fully exposed to price changes. Still, they have managed to cope – though not always smoothly, as it takes time to adjust habits.

The ones who seem to suffer the most from oil price volatility are oil-dependent economies, as is the case with OPEC members. These countries’ economic growth has been spasmodic – rising with oil prices and collapsing with their decline. As a result, their economies are much more vulnerable to oil price variations than probably anywhere else. Understandably, price stability is a priority for them.

From OPEC+ to Super OPEC …

In December 2016, the OPEC+ alliance was formed. The aim was to “rebalance” the market. For economists, markets can always take care of this themselves, without help from outside. However, OPEC+ wanted oil prices to benefit the countries in the group, that is, they wanted them to be higher than what a fully freely functioning market would have set at the time.

The alliance has been successful. Prior to its formation, the oil price was in free fall, heading below $35 per barrel. Thanks to OPEC+, along with involuntary help from countries like Venezuela where supply disruptions have been drastic, prices recovered to above the $70 mark.

Expanding OPEC to include a powerful member that can challenge Saudi Arabia is fraught with complexities.

That outcome was not achieved overnight. The production-cut deal, which was initially for six months, was extended on several occasions. Also, the challenge imposed by tight oil production in North America was too big for OPEC to handle alone. It needed to assemble the biggest alliance in the history of the oil industry to get to where it is today.

To the surprise of many, Russia, which leads the non-OPEC part of the alliance, has proven to be a reliable partner. The entente between Russia and OPEC led some to speculate about the creation of a Super OPEC, where Russia formally joins the organization. This speculation was fueled by statements such as those by Russian Energy Minister Alexander Novak. “We need to build upon our successful cooperation model and institutionalize its success through a broader and more permanent strategically focused framework,” he said. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman was quoted as saying, “We are working to shift from a year-to-year agreement to a 10- to 20-year agreement.”

If the history of OPEC is any guide, expanding the group to include a powerful member that can challenge Saudi Arabia’s supremacy within the organization is fraught with complexities. Furthermore, the market structure of the oil industry in Russia is quite different from that of most OPEC members. Russian oil companies have a strong voice and have not been happy about the OPEC deal.

… to NOPEC

The oil price is not the only challenge on OPEC’s plate. This year, the NOPEC bill has begun to gain traction. The bill’s champion, Senator Chuck Grassley, justified his position as follows: “It’s long past time to put an end to illegal price fixing by OPEC. The oil cartel and its member countries need to know that we are committed to stopping their anti-competitive behavior.”

This is not the first time that U.S. officials have expressed their frustration with OPEC and pursued such a step – the bill was originally introduced in the U.S. Congress in 2000 and has been voted on several times since. However, the bill never passed, as both Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama threatened to veto it. This time, however, OPEC seems to be more concerned, especially given President Donald Trump’s hostile tweets toward the organization, which he has called a “monopoly.” Whether he will endorse the NOPEC bill remains to be seen.

Classification

The NOPEC bill sheds light on a sensitive and yet another divisive issue regarding OPEC: its status either as a cartel – hence subject to anticompetition rules – or just an “organization,” as Ali Al-Naimi, the former Saudi oil minister, once described it in an interview with the Atlantic magazine in 2009. Mr. Al-Naimi added that he, like many of his colleagues, resents the use of the term “cartel” to describe the group.

Several textbooks refer to OPEC as an example of a cartel. In economic theory, cartels have a short life span, since they are difficult to manage and there is a built-in incentive for each cartel member to cheat to safeguard their market share and revenues. Clearly, OPEC’s existence beats the “short life span” concept, but to use the words of Mr. Al-Naimi after he left his official post, “unfortunately, we tend to cheat.”

Morris Adelman described OPEC as a ‘clumsy cartel’.

Renowned economist Morris Adelman described OPEC as a “clumsy cartel”: “Management by a group that cannot accurately predict market demand or production and that does not know how much obedience to expect from its own members is inevitably clumsy and inconclusive.” He added, “such inexactitude leads to price movements that are unpredictable and often sudden and jarring,” which is exactly what OPEC has been trying to fight.

Whether one believes it is a cartel or not, OPEC will not be going away. Yet it will face a bumpy ride as long as tight oil production shows no sign of abating whenever oil prices rise.

In the longer term, and somewhat ironically, OPEC’s influence may well increase as oil loses its appeal. After all, in such a scenario, prices are likely to be low, and the low-cost producers will be the last to leave the market. This would be the case for most OPEC members, who would be better placed to prevent the oil price from dropping, say, from $50 to $5 per barrel than from $100 to $50. This, however, depends on their unwavering commitment to the organization’s survival and on their ability to diversify their economies. Otherwise, the pain might be too strong for them to handle.