Pandemic geopolitics in the Western Balkans

In the Western Balkans, the pandemic could aggravate several pre-existing challenges. If a second wave materializes, the six countries will need considerable foreign assistance to avoid an economic crisis.

In a nutshell

- Governments in the Balkans faced unrest because of the pandemic

- Aid packages only take the first wave into account

- An eventual second wave could spell disaster for the region

This report is part of a GIS series on the consequences of the COVID-19 coronavirus crisis. It looks beyond the short-term impact of the pandemic, instead examining the strategic geopolitical and economic effects that will inevitably be felt further in the future.

The dramatic global changes due to Covid-19 will likely create “pandemic geopolitics,” a phenomenon that will certainly affect the Western Balkans. The fragile regional peace could be shaken.

The question is how to effectively fix the troubled economies and politics of the Western Balkans, long undermined by state capture and unfinished postwar reconciliation. What will be the impact of the coronavirus in a region still going through a post-conflict transformation, with a long road ahead to join the European Union? Even without the pandemic, the Western Balkans would still have its hands full with Kosovo-Serbia relations. For a small region with big problems, the post-Covid recovery will not be easy, especially if a second wave comes.

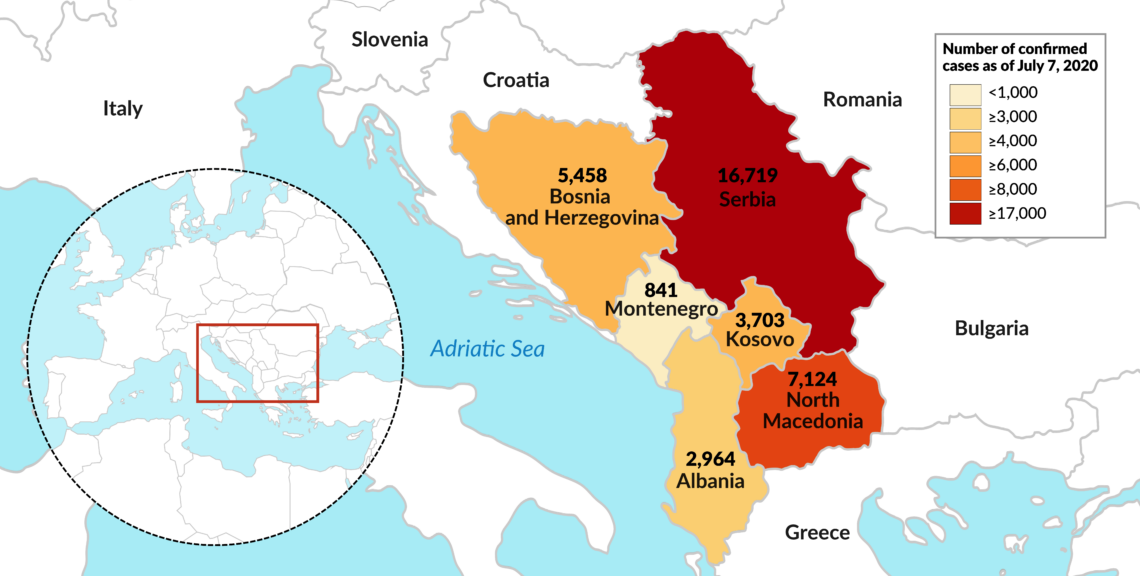

By mid-June, all Western Balkan countries faced a dire situation. The rate of mortality per 100,000 inhabitants as of June 13, 2020, was 8.21 in North Macedonia; 4.90 in Bosnia and Herzegovina; 3.61 in Serbia; 1.68 in Kosovo; 1.45 in Montenegro; and 1.26 in Albania. By the end of June, these numbers were still rising.

Facts & figures

During the first half of 2020, the region’s internal and external borders were closed. In the six states, strict lockdowns prevented citizens from circulating freely. Restrictive measures were even introduced through amendments to the Criminal Code (in Albania), martial law (in Serbia and North Macedonia), or a state of health emergency (in Kosovo). In early July, Western Balkan countries imposed a second lockdown. In Serbia, the decision led thousands of protesters to storm the parliament in Belgrade on July 7.

The region was closed to EU travelers from mid-March till July 1, and then closed again until the end of the summer. Travel between the Schengen zone and the Western Balkans was suspended. Citizens from the Western Balkans were only allowed to enter the EU if the Covid-19 death rate in their country was lower than 16 per 100,000 people over the preceding two weeks.

By mid-June, all Western Balkan countries faced a dire situation.

Considering all these circumstances, 2020 is likely to be a lost year for the region, especially with the pandemic’s resurgence. Now that cases are on the rise again, restrictions will return – and with them, protests.

These developments will likely delay the EU enlargement process in the region. Brussels held online conferences with regional capitals instead of live meetings. The progress reports for Western Balkan countries, scheduled for April, were postponed until the fall. In March, the European Council decided to launch accession negotiations with Albania and North Macedonia, but intergovernmental conferences will probably not start before the end of the year.

Political pandemic

The political impact of the pandemic was obvious. In Pristina, the government lost a vote of no confidence despite it being the most successful in the region at managing the coronavirus. Under ousted Prime Minister Albin Kurti, Kosovo was the only Western Balkan country where the number of cases rapidly fell, and the country had the lowest death rate per capita. These numbers later rose under Prime Minister Avdullah Hoti’s new government. Two other countries, North Macedonia and Serbia, postponed elections. Anti-government protests rocked Serbia (sparked by a renewed lockdown), in Montenegro (a new law targeting church assets) and in Albania (the demolition of the National Theater).

Although threatened with an invisible enemy that does not respect national borders, political elites in the Western Balkans continued to wrestle for power instead of fighting for the health of their citizens. Experts have noted that the crisis is being used as an excuse to backslide on previously achieved progress.

Western Balkan countries received foreign aid from various sources: the United States, (Albania, Kosovo and North Macedonia); Turkey, (Kosovo, Albania and North Macedonia); China and Russia (Serbia); and Austria (Kosovo, Albania, Serbia), among others. But the region’s most important source of support was the EU, which earmarked 3.3 billion euros to support the Western Balkans in tackling Covid-19 and for post-pandemic recovery. Serbia, however, turned down EU aid.

Marshall Plan

What will be the long-term economic consequences for the fragile economies of the Western Balkans? World Bank predictions for 2020 are not optimistic. All six countries will face declines in gross domestic product: North Macedonia by -2.1 percent; Serbia -2.5 percent; Albania -2.8 percent; Bosnia and Herzegovina -3.2 percent; Kosovo -4.5 percent and Montenegro -5 percent.

Unemployment was high in the region before the crisis, and it will increase in the months ahead. Around 70 percent of businesses needed state aid during the crisis period. In North Macedonia, 21,000 employees in private companies did not receive their salaries for three months. In Kosovo, the government intervened with an emergency economic package of 1.2 billion euros. In North Macedonia, a debt freeze scheme was introduced and 28 million euros was given to 325,000 citizens through credit card funds.

All these state measures were introduced to keep the economy afloat. Meanwhile, state budget revenue decreased by approximately 20 percent in the six Western Balkan countries.

No free lunch in Brussels

According to experts, local measures will not suffice without robust international financial support. Through its post-recovery plan, the European Union promised a 1.7 billion-euro assistance package from the European Investment Bank, Team Europe (a coronavirus-crisis support program for non-EU countries) and the Union Civil Protection Mechanism (UCPM), as well as 1 billion euros in grants from the Connectivity Agenda.

Without a strong financial infusion, the six countries will face mass emigration.

Yet as the European Commission has stated, “recovery from the current crisis will only work effectively if the countries keep delivering on their reform commitments,” regarding the rule of law, democratic institutions and public administration.

For the EU, the Western Balkans is still a “geostrategic priority,” and individual countries remain “partners,” but Brussels’ support is given on the condition that governments tackle fundamental reforms. The aid is meant for the region’s citizens, not its political elites – and certainly not its anti-reformist elite. That means the pandemic should not be an excuse for pausing these reforms.

All these measures and intervention packages were calculated to offset the consequences of the pandemic for the first half of the year. But what if the coronavirus returns after the summer, and rages on into next year?

Scenarios

Second wave

A second surge in infections comes to the Western Balkans, but thanks to international aid and first-wave experience, the region copes with the health challenge. However, the area falls into a deep economic crisis, similar to that of 2008. The economies of the six Western Balkan countries do not recover in 2020, putting the region in limbo. Private businesses fail, shrinking tax revenues – which in turn lead to social spending cuts and economic distress, inevitably giving rise to political tension as well.

No second wave

A coronavirus vaccine is developed and the dramatic public health chapter of the crisis is closed. Economically, financial recovery takes place throughout 2021 and 2022. Under these circumstances, if the EU fails to come up with a Marshall Plan-type initiative for the Western Balkans for the years 2021-2024, the region will collapse into its biggest postwar economic crisis with all the accompanying political and security challenges.

Most likely, without a strong financial infusion, the six countries will face mass emigration and the whole region will experience a financial crash, triggering state failures. The combined burden of the unfinished peace process, the numerous contested borders and, most importantly, the unresolved issue of Kosovo-Serbia relations, will make any future stabilization even more daunting than before.